|

Against Romanticism: From Enlightenment to Enfrightenment and the Culture of

Slavery

by Caoimhghin ” CroidheŠin

This book looks at the philosophy, politics and history of many different art

forms arguing that Romanticism is dominating modern culture to the detriment of

Enlightenment ideals. In recent times Enlightenment ideas have been

characterised as cold, hard science, while Romanticism has been perceived as the

'caring' philosophy.

However, Romanticist emotions lead to

self-absorption, escapism and diversion, yet during the Enlightenment, emotion

was not only a very important part of Enlightenment philosophy but was the basis

of the philosophes' ideas for combating injustice in society. Throughout the

last two centuries, any Enlightenment movements that tried to highlight the

plight of the poor or unite the working class (Sentimentalism, Realism, Social

Realism, Socialism) have been excluded, swamped or submerged by Romanticist

movements that ultimately pose no threat to the status quo.

.

Kindle version now available on:

amazon.com /

amazon.co.uk

In other words, just as the Right tries to

remake the Left in its own image (to disarm it), the Romanticists try to remake

the Enlightenment in theirs (catharsis without progressive social change), thus,

maintaining a 'culture of slavery'.

Through developing an awareness

of the socio-political fault lines in today’s culture, cultural practitioners

can create a new democratic spirit (a ‘culture of resistance’) emphasising the value of ordinary

people, while at the same time making an important contribution to the fight

against poverty, oppression, and injustice.

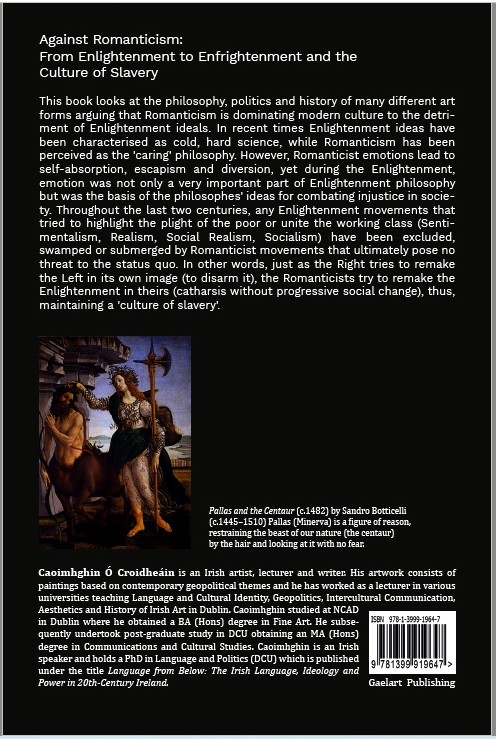

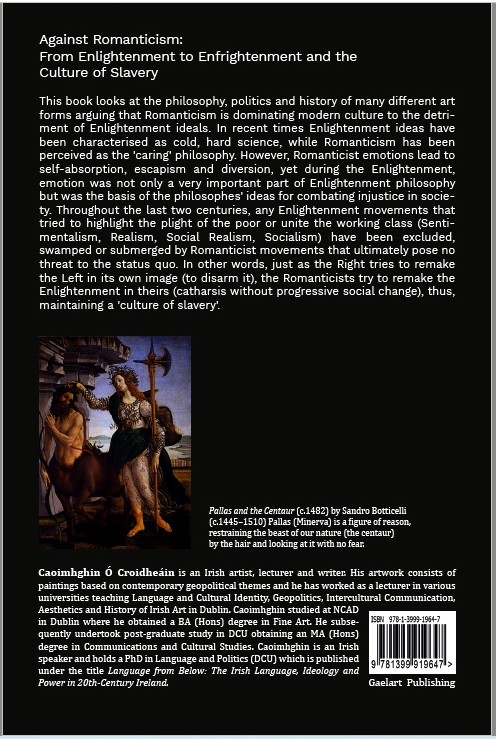

Back cover image:

Pallas and the Centaur (c.1482) by Sandro Botticelli

(c.1445–1510). Pallas (Minerva) is a figure of reason,

restraining the beast of our nature (the centaur)

by the hair and looking at it with no fear.

Gaelart Publishing

ISBN: 978-1-3999-1964-7

Design: Ieva Grbacjana (https://igrbacjana.com/)

Cover photography: Philip O’Neill (https://www.philiponeillphotography.com/)

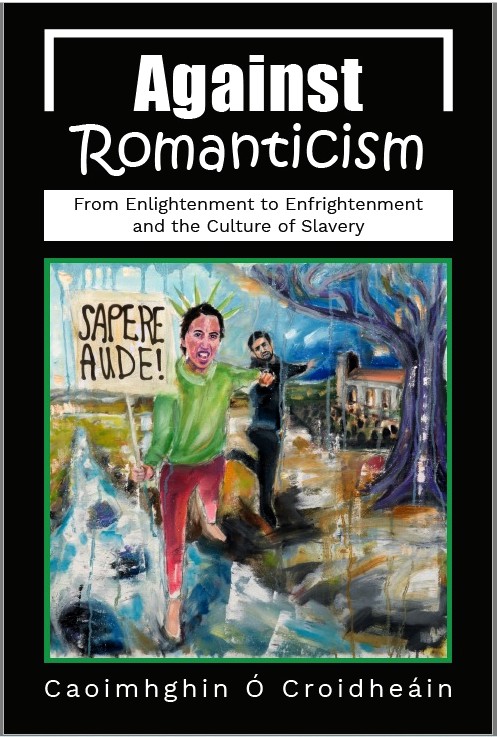

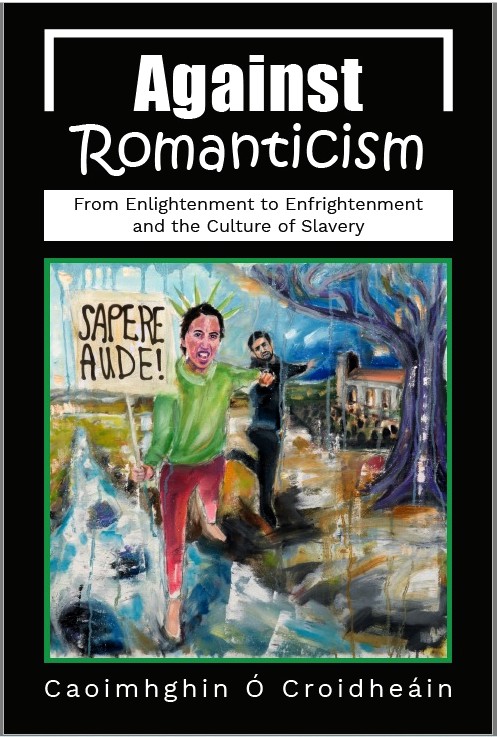

Cover painting: Sapere Aude! by Caoimhghin ” CroidheŠin (http://gaelart.net/)

Back cover: Pallas and the Centaur (Public domain / Wikimedia Commons)

Printer: Paceprint (https://paceprint.ie/)

Typeset in 12pt Cambria and 10pt Work Sans

Size: 6" x 9"

Pages: 357

Weight: 750g

Material Cover: 350gsm Silk

Printing Text: 4 process colours throughout

Material Text: 90gsm Silk

Printed in Dublin in paperback only.

Publisher: Gaelart Publishing (Caoimhghin ” CroidheŠin)

Full colour illustrations throughout.

Link:

http://gaelart.net/againstromanticism.html

***

Contents:

Acknowledgements

Introduction

What’s the matter with Romanticism?

Chapter 1 - Philosophy

Re-Examining Emotion and Justice in Enlightenment Ideals

Chapter 2 - Politics

Romanticism as a Tool for Elite Agendas

Chapter 3 - Art

Art Movements and the People’s Movement

Chapter 4 - Music

The Conversion of Music into a Mass Narcotic

Chapter 5 - Opera

Opera in Crisis: Can It be Made Relevant Again?

Chapter 6 - Dance

Diversity in Dance Today

Chapter 7 - Poetry

The Dialectics of Rhyme

Chapter 8 - Literature

Literature Serving Human Liberty

Chapter 9 - Theatre

Popular Theatre as Cultural Resistance

Chapter 10 - Architecture

Neoliberalism, Climate Change and Architecture

Chapter 11 - Cinema

Individual and Collective Struggles in Cinema

Chapter 12 - Television

Game of Thrones: Olde-Style Catharsis or Bloody Good Counsel?

Chapter 13 - Culture

The Culture of Slavery v the Culture of Resistance

Conclusion

The Power of Romanticism today: 21st Century Irrationalism

Bibliography

Index

***

Caoimhghin ” CroidheŠin is an Irish

artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on

contemporary geopolitical themes and he has worked as a lecturer in various

universities teaching Language and Cultural Identity, Geopolitics, Intercultural

Communication. He currently works for Boston University in Dublin teaching

Aesthetics, History of Irish Art and drawing in DCU (All Hallows). Caoimhghin studied

at the National College of Art and Design in Dublin where he obtained a BA (Hons)

degree in Fine Art. He subsequently undertook post-graduate study in the

interdisciplinary field of Cultural Studies in Dublin City University obtaining

an MA (Hons) degree in Communications and Cultural Studies. Caoimhghin is an

Irish speaker and holds a PhD in Language and Politics (Dublin City University)

which is published under the title Language from Below: The Irish Language,

Ideology and Power in 20th-Century Ireland.

Caoimhghin is a regular contributor of articles on the arts, Irish culture,

cultural politics, and the environment, to sites such as Global Research,

Dissident Voice, CounterPunch and 21cir.

***

Introduction to Against Romanticism

What’s the matter with

Romanticism?

All artforms are in the service of the greatest of all arts: the art of

living.

Bertolt Brecht

We are all raised in a culture of Romanticism, an amorphous

ideology that saturates cultural and political beliefs in society today.

Romanticism is defined by its emphasis on subjectivity, emotion and

individualism. It has pervaded all the arts, society and politics and its

individualism is an essential aspect of ideologies such as Modernism,

Postmodernism, Nationalism, and Neoliberalism. Romanticism arose as a reaction

to the Age of Enlightenment, a period of time when intellectual and

philosophical movements discussed and developed ideas on liberty, toleration,

progress, separation of church and state, and constitutional government.

The early Romanticists appeared progressive in that they reacted to the extremes

of the Industrial Revolution but then advocated a return to medieval ideas about

society and production. However, the height of Romanticism coincided with the

development and rise of socialist ideology. The socialists also criticized the

Industrial Revolution but from a very different perspective. They were more

concerned with the poverty and extremes of wealth inequality created by laissez

faire capitalism, especially questioning individual control of the means of

production.

Thus, it can be argued that the Romanticists wanted to see a move backwards to

the individualist feudal ways of doing things rather than giving in to the

potential of a collectivist future. In the arts Romanticism emphasized intense

emotion, horror and awe of the beauty of nature in opposition to Enlightenment

ideas derived from the naturalism of the Greek and Roman classics and empirical

reason.

The Enlightenment philosophers also used rational thinking to fight the extreme

forms of social injustice prevalent at the time. They opposed absolute monarchy,

torture and the death penalty, questioned religious orthodoxy, while supporting

concepts of free speech and thought, republicanism and revolution, separation of

church and state, and a civil order based on natural law.

As Romanticism gave way to Realism a pattern emerged of Romanticist-influenced

movements (Modernism, Postmodernism, Metamodernism) competing with

Enlightenment-influenced movements (Realism, Social Realism, Socialist Realism).

The descendants of the Romanticist movement all had in common the

antirationalist rejection of Enlightenment thinking, while the descendants of

the Enlightenment continued with ideas of liberty, exposing colonialism and

working-class poverty, and depicting resistance to oppression.

Today, as in the past, there is still an ideological conflict in society between

a diversionary, escapist culture (which is dominant, hegemonic and well-funded)

and a culture of criticism and resistance (which is in the minority and barely

funded, if at all).

Inside this diversionary, escapist culture we are led to believe that all is

fine and we only need to work, relax and enjoy life while our politicians take

care of any local, national and international issues. However, these

‘background’ issues are not steady, unchanging facets of life. They are dynamic,

belligerent and dangerous.

We are sinking into a quicksand of Romanticism leaving elites free to carry out

war agendas on a global scale. There is a gradually developing showdown between

the current unipolar world and the fast-developing pressure for a multipolar

world.

While it is considered that the history of Romanticism has been problematic, it

is still perceived to be ‘better’ than the history of science, which, through

the development of ever more sophisticated technology, is thought to be

increasing and refining exploitation of human and natural resources, and

therefore, ultimately destroying the planet.

However, is this true? This book attempts to reexamine the effects of

Enlightenment and Romanticist ideas on society today while at the same time

exploring their history and origins in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Chapter 1

Chapter 1 looks at the original intentions of the Enlightenment philosophers

showing that the main motivating force for their endeavors was not just to

maintain the scholarly work of Renaissance humanism but to develop the ideas

necessary for democratic institutions and the fight against social injustice in

all its forms. Far from being cold rationalists, the Enlightenment philosophers

were moved emotionally by the society around them to try and effect positive

changes, thus explaining the use of the term Sentimentalism to describe the

Enlightenment artforms that tried to expose the plight of the poor. The

conservative and aristocratic nature of German Romanticism is examined as well

as the working-class perspectives on Enlightenment and Romanticist philosophies,

as analyzed by Marx and Engels, who saw a connection between Enlightenment ideas

and socialism.

Chapter 2

Chapter 2 shows the effects of Enlightenment and Romanticism on politics.

Philosophers like Montesquieu wrote about concepts of citizenship and republican

government that would replace one’s status of being a subject under the absolute

rule of monarchies. The Romanticist emphasis on cultural, linguistic and ethnic

nationalism arose in opposition to the burgeoning liberal and socialist

movements of the time. By the twentieth century competing nationalisms led to

the tragedy of the Great War and then to the extreme ethnic nationalism of

national socialism in Germany and the Second World War. Since then the influence

of Romanticism can still be seen in the rise of supranational entities and

postnationalism, from, for example, a ‘German’ national identity to a ‘European’

national identity (rather than international working-class solidarity).

Chapters 3 to 12

Chapters 3 to 12 apply these ideas to various artforms: art, music, opera,

dance, poetry, literature, theatre, architecture, cinema, and TV. The history of

each form since Enlightenment times is examined and the effects of such ideas on

form and content is contrasted with the form and content of Romanticist

movements. As Romanticism pulled the arts in ethereal and escapist directions,

resistance culture examined the plight of the oppressed using different forms

such as naturalism, realism, social realism, as well as working-class socialist

realism. In more difficult times these fundamentally different Enlightenment and

Romanticist approaches to the arts came into conflict with each other and at

other times one took over from the other depending on the changing

socio-political circumstances. The overwhelming influence of Romanticist ideas

today can be attributed as much to the repackaging and sale of mass suffering as

catharsis, as to the massive financial support given them by global entities.

Chapter 13

Chapter 13 summarizes these ideas into a general analysis of culture that goes

in two opposite directions. One that diverts the attention of people away from

exploitation (the culture of slavery) and another which aims to create awareness

of how such exploitation operates (the culture of resistance). This chapter also

shows that while science and technology are responsible for much exploitation of

people and resources, modernity cannot be reduced to the domination of nature

and human beings by science. Many progressive movements and changes were brought

about by Enlightenment ideas and these ideas are an essential aspect of the

different forms that the culture of resistance takes today.

Conclusion

On a broader level, the connection between Romanticism and the problematic

history of irrationalism is discussed in the Conclusion and shows the continuing

importance of rational thinking as the basis for future action.

Through developing an awareness of the socio-political fault lines in today’s

culture, cultural practitioners can create a new democratic spirit with an

emphasis on the value of ordinary people, while at the same time making an

important contribution to the fight against poverty, oppression, and injustice.

|