|

Biography

Art Works

Blog

Research

Articles

|

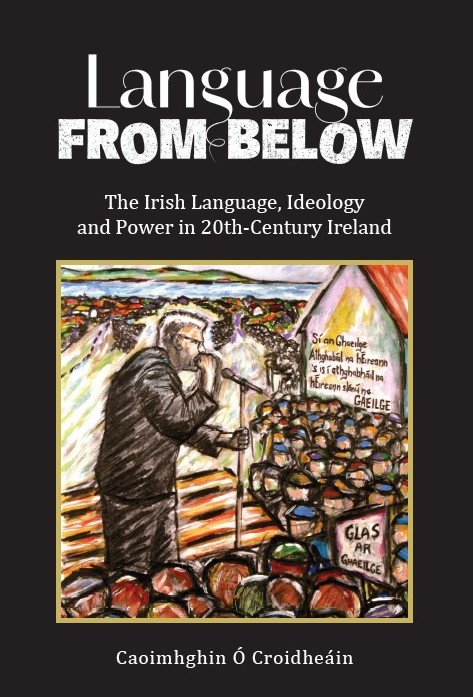

Language from Below: The Irish

Language, Ideology and Power in 20th Century Ireland

'An

audacious and insightful study of a controversial topic, this book brings to the

debate about the fate and future of the Irish language a shrewd blend of realism

and analytic rigour. It shows how the question of Irish has always been bound up

with the conflict of social classes within the island. An intrepid and deeply

thoughtful work.'

Prof Declan Kiberd

|

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin

(see also art website)

ABSTRACT

The main objective of this book is to critically investigate the

relationship between the Irish language and politics through a survey of

individuals and movements associated with the language. It is proposed that the

status of the Irish language is dependent on the political ends or needs of

élites in Irish society. This approach takes into account competing socialist

and nationalist perspectives on language and society to demonstrate the

different motivations for and class interest in Irish.

A critical analysis of the theories of

Ideology, Nationalism and Ethnicity lays the basis for an in-depth examination

of the changing relationship between the Irish language and politics since the

formation of Conradh na Gaeilge in 1893. The book also proposes possible

future directions for the positive development of the Irish language under the

main headings of Community, Education, State and Politics.

It proposes

that the present decline of the Irish language is part of a global system of

international capitalism that seeks to homogenise markets by reducing national

and linguistic boundaries, thereby increasing power and profits at the expense

of the well-being and autonomy of national populations. Therefore, the struggle

against linguistic homogenisation must become an essential element of political

opposition to the power of such élites. A key argument underlying the book is

that the struggle for rights is transformational and the assertion of language

rights by individuals and communities plays an important part in changing the

general relations of power.

Table of Contents:

Acknowledgements

Foreword

Introduction

Chapter 1 Ideology

Chapter 2 The Nation, Ethnicity and Language

Chapter 3 Language Policy 1893–1945

Chapter 4 Language Policy 1946–2000

Chapter 5 Progressive Politics

Conclusion

Appendix

Bibliography

Index

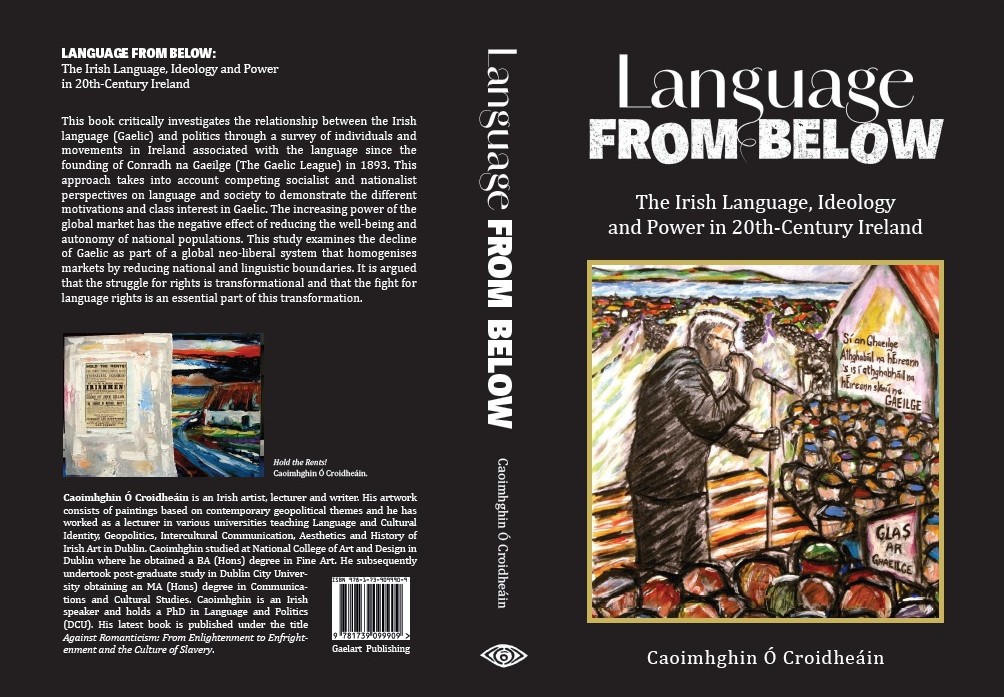

Back cover:

This book critically investigates the

relationship between the Irish language and politics through a survey of

individuals and movements associated with the language. This approach takes into

account competing socialist and nationalist perspectives on language and society

to demonstrate the different motivations for and class interest in Irish. The

increasing power of the global market has the negative effect of reducing the

well-being and autonomy of national populations. The study examines the decline

of the Irish language as part of a global neo-liberal system that homogenises

markets by reducing national and linguistic boundaries. It is argued that the

struggle for rights is transformational and that the struggle for language

rights by individuals and communities is an essential part of this

transformation.

The Author:

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin went to the National College of Art and Design, Dublin,

and obtained a B.A. in Fine Art in 1985. He subsequently attended Dublin City

University and obtained a Masters Degree in Communications and Intercultural

Studies in 1993 and his Ph.D. in 2000. He was a Post-Doctoral Fellow at the

Centre for Translation and Textual Studies in Dublin City University, Ireland

from 2002 to 2005. He is currently working as an artist and critic in Dublin.

Book Review:

The Irish Language and Marxist Materialism

by Kerron Ó Luain (June 12, 2019)

“The night of the sword and bullet was followed by the morning of the chalk and

the blackboard. The physical violence of the battlefield was followed by the

psychological violence of the classroom. But where the former was visibly

brutal, the latter was visibly gentle”

The above, written by renowned Kenyan thinker Ngũgĩ wa

Thiong’o, sums up much that is at the heart of Caoimhghin

Ó Croidheáin’s

persuasive book here under review.

Language From Below: the Irish language, ideology and power in 20th

century Ireland examines the relationship between material forces

and the ideology surrounding the Irish language during the past century or

more.Little treatment has been given to this

subject, especially in book length. Hence, the reasons for the varying

attitudes that exist towards the Irish language – some of them positive,

others hostile, many apathetic – are not well understood. Often, in the face

of opposition, instead of turning to class or economics as explanatory

factors, proponents of the language frame hostility to An Ghaeilge

in simplistic “anti-Irish” terms.

Ó Croidheáin admits that Irish occupies a strange

place in the national consciousness; “it is true that not many Irish people

speak the Irish language, yet many Irish people still define their identity

in terms of the Irish language”. He thus seeks not only to address common

misinterpretations, but to offer solutions that may remedy the current

decline the Irish language is facing in its western communal heartlands, and

the pressures it faces in other spheres.

By getting to the economic “root” of language decline,

as it were, he sets out his stall for a reversal of fortunes in explicit

Connollyite terms.

The book consists of five chapters and Ó Croidheáin

opens with a theoretical exploration of Marxism, ideology and language. As

he explains, “in each historical period the ruling ideology is separated

from the ruling class itself and given an independent existence”. At times,

according to French philosopher Louis Althusser, this phenomenon could be

relatively autonomous and act as a “social cement” even among non-élite

sections of the populace.

For a period in the late nineteenth and early

twentieth century, Irish fulfilled this role. It became first a “political

weapon” and marker of autonomy, and then, once the state was founded, an

instrument of social cohesion – only to be replaced later in the Free

State’s existence by Catholicism during the 1930s.

In writing about colonialism and language Ó Croidheáin

turns frequently to Ngugi, the Irish educationalist and revolutionary

Pádraig Pearse, and Brazilian educator Paulo Freire. He outlines the

ideological power of the English education system in Ireland, Kenya and

further afield in turning the colonized against their own cultures.

He also explores the debates among what might be

termed decolonial literary figures around the use of the native tongue, the

tongue of the colonizer, and translations, in their writings. For Frantz

Fanon, in his essay “On National Culture”, in

The Wretched of the Earth:

“The crystallisation of the national consciousness

will both disrupt literary styles and themes, and also create a

completely new public. While at the beginning the native intellectual

used to produce his work to be read exclusively by the oppressor,

whether with the intention of charming him or denouncing him through

ethnical or subjectivist means, now the native writer progressively

takes on the habit of addressing his own people”

The author is always aware, however, of how resistance

to colonialism in the form of nationalism could be manipulated by the ruling

class. Thus, the advent of a cultural nationalism and its attendant “class

conciliatory ideology” in Ireland with the arrival of Thomas Davis and the

Young Irelanders, writing in The Nation during the 1840s, is viewed

as the starting point for this opportunity for social control by later

nationalist leaders.

Ó Croidheáin subsequently utilizes the work of early

modern English and French philosophers, such as John Locke and Jean-Jacques

Rosseau, to explain “the conflation of nation and state”. For Rosseau, as a

member of the rising bourgeoise, the state exists above all to defend

individual rights of property in the face of tyrannical monarchy.

As the bourgeoisie came to rule France following the

revolution of 1789, the French state consolidated to the detriment of the

various nations within it, not least of which were the Bretons and the

Basques. The languages of both, as with various French dialects, or

patois, came under increasing pressure from a centralized Parisian

French language.

This type of utilitarianism also manifested in Ireland

regarding Irish. The thinking of English political economists such as John

Stuart Mill were readily absorbed by Catholic nationalist leaders like

Daniel O’Connell during the mid-nineteenth century who proclaimed of the

language that he was “sufficiently utilitarian not to regret its gradual

passing”.

A cultural revolution or a material one?

Others, however, such as Douglas Hyde, had different

ideas and wrote of the necessity of “De-Anglicising” Ireland. A cultural

revolution gained traction in the 1890s – the establishment of Conradh

na Gaeilge (The Gaelic League) in 1893 a seminal moment.

The Conradh waged – in a modern, secular way

– several rights-based battles in its early years, attaining an improved

status for Irish within the British-run education and postal systems. At its

Ard Fheis (annual meeting) in 1915, radicals staged a coup and

moved the organization towards inserting itself at the heart of the tectonic

shifts underway in Irish politics by taking a separatist stance. Hyde, who

contended that the language issue should remain apolitical, resigned.

Yet, six of the seven signatories of the 1916

Proclamation were members of the Conradh. Their involvement in the

Easter Rising, and the series of events in subsequent years, not least the

Black and Tan War, left an indelible mark on Irish society, culminating in

quasi-independence and the foundation of the Twenty-Six County Irish state

in 1922.

However, the Civil War of 1922-23, where

British-backed Free State forces, allied with the Catholic Church, strong

farmers, and big business, suppressed the radical republican forces,

heralded a new dawn for the Irish language. As Ó Croidheáin explains, “the

desire for genuine social change behind the revolutionary movement was

diverted into cultural change in the form of Gaelicisation policies”. The

language was essentially wielded as a tool of counter-revolution.

These policies, moreover, were largely confined to the

education system, and there was a lack of fundamental change in the social

structure that might allow the language to thrive once more. Thus, any gains

made through schooling in the 1920s “were constantly being undermined by the

reality of unemployment and education”.

In the 1930s, Éamon De Valera, Taoiseach (Prime

Minister), and leader of the populist nationalist Fianna Fáil party, placed

Catholicism centre-stage as a marker of Irish identity – particularly during

the Eucharistic Congress of 1932.

During the inter-war years, nationalist ideology,

incorporating both the Irish language and Catholicism, served as an

instrument of state consolidation. Élites utilized this communal “glue” to

bind ordinary people to the ideology of the state – particularly at points

when the state felt itself under threat, as it did from the IRA during the

1930s and into the 1940s during the Second World War, when the Free State

sought to preserve its neutrality above all else. But this unholy alliance

between state and language was counterproductive in many ways too:

“The status of Irish in the education system and state

institutions, burdened the language with an ideological slant that had

implications for the working-class and the people of the Gaeltacht. Language

policy was perceived as discriminatory among the poorly educated who saw

Irish in terms of reward or sanction for social mobility”

Measures to restore the Irish language to national

prominence as anything more than a symbolic marker of identity began to be

reversed in the 1960s. Following the adoption of T.K Whittaker’s

Programme for Economic Expansion by these same élites in 1958,

appealing to external market forces, rather than economic nationalism,

became the order of the day.

With the demise of economic nationalism, came a

corollary demise in cultural nationalism, and the status of the Irish

language in the civil service began to be eroded. This process, whereby the

language no longer served the ruling-class, was only intensified with the

joining of the European Economic Community in 1973. Now wealth was to be

gained, and protected, through economic liberalism and English

monolingualism.

The situation has remained largely unchanged since, as

Ó Croidheáin is keen to point out; “today, neo-colonialism in the form of

Anglo-American mass culture and multinational industry provides the engine

for a new language colonialism as the English language gains dominance in

global culture”

Empowerment

However, Ó Croidheáin is not despondent, and

throughout the book, but particularly in the final chapter, he goes to great

lengths to highlight the transformative nature of struggle. One example he

provides is that of Norway during the late nineteenth century where the

Landsmål movement, proponents for a peasant dialect, in opposition to

speakers of the upper-class Bokmål dialect, managed to inspire “the

peasantry to question and challenge the power relationships inherent in the

centre/periphery of the society”.

In Ireland, he points to the transformative struggle

taken up by the people of Ráth Chairn, a small Gaeltacht colony in

the east of the country in Co. Meath. Led during the mid-1930s by the great

literary figure and activist, Máirtín Ó Cadhain, the activism required to

establish the settlement, achieve recognition as a Gaeltacht, and

attain the necessary infrastructure over the course of years, empowered

those involved, making them keenly aware of their rights as citizens.

Likewise, during the late 1960s and early 70s in Gluaiseacht Chearta

Sibhialta na Gaeltachta (Gaeltacht Civil Rights Movement), a similar

empowerment was also discernable.

For Ó Cadhain, this struggle was not only about the

preservation of the language as it was for some (what Ó Croidheáin calls the

“culturalists”), nor was it simply for more “rights”, but it was far broader

than that. During the fiftieth commemoration of the Easter Rising in 1966, Ó

Cadhain argued that;

“henceforward the Irish language movement would

have to play an active role in the struggle of the Irish people to

fulfill the aims of the 1916 Manifesto. This is the Reconquest of

Ireland, the revolution, the revolution of the mind and heart, the

revolution in wealth distribution, property rights and living

standards”.

Other positive developments such as the surge in

all-Irish language schooling, the Gaelscoil movement, from the

1970s, in both the southern and northern states in Ireland, are identified

by Ó Croidheáin. Taking the case study of Scoil an tSeachtar Laoch

in working-class north Dublin, he demonstrates how the struggle for

resources by parents in the face of opposition by church and state, led to

the cultivation of “self-respect, self-sufficiency and fearlessness”.

Even here, however, he offers a salutary caution – and

one that has proven prophetic, whereby the years 2017-2018 were the first

where the state has arrested the growth of the Gaelscoil movement

since its inception in 1973.

Ó Croidheáin, writing in 2006, warned that “without

developing a wider political critique of society such movements may lose

their collective force and be assimilated back into the dominant ideology of

the state”.

All told, the author makes a forceful case for Irish

language activists, atá ag treabhadh an ghoirt, to move from a simple

“culturalist” or rights-based discourse and activism to a philosophy which

unambiguously advocates for a wholesale redistribution of power and wealth.

As he affirms, “linguistic issues can only be resolved when class questions,

such as the ownership and control of resources, becomes part of the overall

objective of political movements”.

Or, as Ó Cadhain boldly stated, “sé dualgas lucht na

Gaeilge bheith ina sóisialaigh” (it is the duty of Irish speakers to be

socialists).

Finally, and perhaps without realizing it,

Ó Croidheáin also

demonstrates clearly the untapped potential for a progressive movement that

combines the socialism of James Connolly with the cultural qualities and

socialism of Ó Cadhain, the Gaelscoil movement and the struggle to

maintain the Gaeltacht. Recent surveys, for example, have

demonstrated how 25% of parents in the state would send their children to a

Gaelscoil if the opportunity existed, but that around only 4% can

avail of this, while

another poll showed that 60% believed the language was very important

and should be supported.

Yet, certain sections of the Irish left adhere to a

minimalistic rights-oriented discourse when it comes to the Irish language.

There is a refusal to seriously engage with this dormant potential for fear

of being branded “nationalist” and “reactionary”.

The recent local and European elections – in which the

radical and broad left took a hammering – have demonstrated once again that

another layer of activism, above and beyond mere economism, is required to

keep people engaged, especially in times of limited political mobilization.

It is not enough to complain that there was no

fervently active social movement on housing to galvanize workers into

turning out and voting, like there was around the issue of water in 2014.

The same groupings, despite the fact they count many Irish speakers among

their ranks and in prominent positions, have never run an Irish language

class for the benefit of the public in the entirety of their existence.

Identity is important to people.

Additionally, as Freire remarked, “without a sense of identity, there can be

no real struggle”. Unlike transient moods surrounding politics and the

economy, identity tends to remain fixed. Crucially, the Irish language, as a

signifier of identity, transcends ethnic divisions and is no longer rigidly

associated with “white ethnic Irish Catholicity” – if it ever really was.

The Irish language could be harnessed through a

grassroots movement to build a new, secular and inclusive Republic,

encompassing all colors and creeds. It is up to the left to muster the

political will to do so.

Dr Kerron Ó Luain is an historian

from Dublin, Ireland. His latest journal article, featured in Irish

Historical Studies, examines

the links between agrarian violence and constitutional politics on the

Ulster borderlands in the wake of the Great Famine. Twitter @DublinHistorian

See:

https://www.counterpunch.org/2019/06/12/the-irish-language-and-marxist-materialism/

Book Review:

Mind your language

by Eamon Maher (13 December 2006)

Political weapon, tool of the elite, torture for

schoolchildren. Caoimhghín Ó Croidheáin's thoughtful study is a welcome critique

of the demotion of the Irish language. By Eamon Maher

Mick McCarthy and Roy Keane in Saipan. Everyone has an opinion on it, often one

that is informed by a negative experience of the way Irish was taught, or the

favours bestowed on those who were proficient in the language in the form of

extra marks in state exams or secure jobs in the civil service. Then there are

those who, like myself, believe that our national language is an integral part

of our identity and that, in an era of mass globalisation, cultural specificity

should be jealously guarded. In a thoughtful preface, Michael Cronin notes: “As

the world faces into the prospect of linguacide on an unprecedented scale, the

local lessons of Irish have global significance. As more and more languages are

forced into extinction... by a small clutch of major languages, then how

societies or governments or communities try to deal with these pressures is of

importance to every inhabitant on the planet who sees language as an inalienable

right rather than as an optional extra.”

Ó Croidheáin points out from the outset that while most people genuinely

appreciate Irish “as an important symbol of cultural distinctiveness”, there are

others who “have considered the language important as a means for fulfilling

particular political objectives in the past and may do so again”. With any issue

as emotive as one's national language, there is always scope for jumping on the

bandwagon for ideological or political purposes. The fact that Ireland is a

former colony of one of the great world powers, England, always made the

language of the coloniser difficult to resist. But, as Ó Croidheáin points out,

we could quite easily have decided to be a bilingual society, a path followed by

some other EU states. In this book, the Kenyan writer Ngugi wa Thiong'o argues

how in the colonising process the languages of the captive nations were “thrown

on the rubbish heap and left there to perish.” Ngugi, in a move reminiscent of

the Limerick poet Michael Hartnett, bid farewell to English in favour of his

native tongue, Gikuyu. He refused to buy into the view that associated Kenyan

languages with “negative qualities of backwardness, underdevelopment,

humiliation and punishment”.

Joyce was aware the particular form of Hiberno-English he used was different

from that of the coloniser, but by adopting the ‘acquired speech' he developed a

new and remarkable language. The ghost of Gaelic has never been completely

eradicated from the distinctive and original way in which the Irish use English:

undoubtedly one of the reasons for the flowering of our creative writers. In the

19th century, Matthew Arnold chose to see the Irish people as “feminine” Celts

and the English as “masculine Teutons” in a dialectic that conveniently placed

the Irish in a position of subservience. Part of the colonial project involves

the control of a people's culture (of which language is a major component) and,

according to Ngugi, determining the tools of self-definition in relation to

others is one of the main methods of mastering the mental universe of the

colonised. Douglas Hyde, in his 1892 speech on ‘The Necessity for De-Anglicising

Ireland', “heralded a qualitative change in the struggle to maintain and develop

the popular basis of support for the Irish language”.

Hyde argued that the process of ‘de-anglicising' was not in any way a protest

against what was best in English people, “but rather to show the folly of

neglecting what is Irish and hastening to adopt, pell-mell, and

indiscriminately, everything that is English, simply because it is English”. The

work of Conradh na Gaeilge, so energetically promoted by Hyde and Eoin MacNeill,

at times flirted with radical nationalism. One particularly acrimonious issue

was whether there could be an Irish literature in the English language. In

addition, some wondered whether it was possible to “create a separate Irish

cultural identity which would, at the same time, include Irish men of different

traditions”. The romantic image that developed among the new Catholic

bourgeoisie of the life of the Gaeltacht inhabitants neglected the harsh

realities with which they were faced. The Catholic church also saw potential in

this simple lifestyle. Ó Croidheáin writes: “The ‘spirituality' of the Gaeltacht

and the spirituality of Catholicism merged in the depiction of the people of the

Gaeltacht as morally superior despite widespread poverty.” Irish was often used

as a political weapon by elements within both church and state to further their

own aims. Thus, after the 1916 Rising, language became the site for conflicting

political ideologies.

On the thorny issue of language policy, Ó Croidheáin skilfully displays the lack

of a coherent approach adopted by successive governments. Compulsory Irish,

various white papers and reports – all these ultimately failed in their

objective to optimise the use of the language in society. The main point made by

Ó Croidheáin in this regard is that “the promotion of the language falls back on

voluntary organisations in the absence of legislative powers to ensure its

development as a living language”. Legislation that fosters a view of Irish

merely having a utilitarian value for the better educated has not served the

language well. This value has been eroded in recent years to such an extent that

a recent IDA poster campaign fails to even allude to the language spoken in

Ireland, so widespread is the perception that English is the official language

in this country.

Ó Croidheáin argues that it is through politics that the status must be changed:

“The Irish language will be best served by that politics which does not

necessarily applaud it for its symbolic role as the main vehicle for Irish

identity but rather creates the environment for it to grow and develop.” This

book is a welcome critique of how Irish has been demoted to the status of a

“language from below”. Ó Croidheáin's book could see a debate begin, free from

the ideological and political restraints that have plagued the language's

progress in the past.

Eamon Maher is Director of the National Centre for Franco-Irish Studies in ITT

Dublin (Tallaght) and the author of a number of books.

See:

https://magill.ie/archive/mind-your-language

Foreword to

Language from Below

by

Prof. Michael Cronin

In a lecture delivered before the Cork National society on the 13 May 1892,

William O’Brien MP warned his audience against substituting piety for politics

on the question of language:

It was emigration […] that drove the Irish language out of fashion. Once the

eyes of the Irish peasants were directed to a career in the golden

English-speaking continents beyond the setting sun, their own instincts of

self-preservation, even more than the exhortation of those responsible for the

future, pointed to the English language as no less essential than a ship to sail

in and passage ticket to enable them to embark on it, as a passport from their

miserable surroundings to lands of plenty and independence beyond the billows.

[1]

Although O’Brien’s prose is replete with the rhetoric of his age and cannot

quite escape the dragnet of Arnoldian sentiment, he is enough of a politician to

know that those who vote with their feet are as eloquent in their own way as

those who gesticulate with their hands. Language may be discussed in texts, but

it survives or perishes in contexts. What those contexts might be and how we

might describe them has generally been left to the linguist as if the proper

business of politicians was to run the world and for the linguists to parse it.

What O’Brien suggested to his Cork audience, however, is that to understand what

happens to a language is to understand what is happening to a society and an

economy and even more importantly, what is happening ‘beyond the billows’.

In that wider world which is the setting for Irish linguistic fortunes, there

are not only ‘lands of plenty and independence’ but ‘miserable surroundings’

that have brought other language communities to their knees. That misery and

plenty often share the same space is borne out by the catastrophic incidence of

language death in such favoured Irish emigrant destinations as Australia and the

United States of America. Yet despite the ample evidence that the Irish are not

alone in their linguistic predicament, there has been a remarkable reluctance

until very recently to see the situation of Irish as ominously routine in its

mistreatment rather than tragically exceptional in its treatment. Caoimhghin Ó

Croidheáin in Language from Below performs a signal service by opening up

debates on Irish to the news from elsewhere. In particular, he interrogates very

fundamental questions relating to ideology, ethnicity and class and brings to

bear the insights of a whole array of thinkers to tease out the issues involved.

The theoretical excavation is all the more necessary in that many debates

conducted around language in Ireland assume that history is more a matter of

opinion than record and that social class is a marketeer’s statistical whim

rather than a ruthlessly enforced aspect of social life. More specifically,

Language from Below, repeatedly shows how language fortunes are bound up

with the political choices and economic positioning of a society. In other

words, language is not only words but is part of or not, as the case might be,

the broader political project in which the society is engaged.

Language from Below is alive to the ironies of a language of the

dispossessed which became the language of possessors while the dispossessed were

encouraged in Seamus Deane’s phrase to stay quaint and stay put. The work

details the manner in which the Free State government and its Fianna Fáil

successors mobilised Irish to copper-fasten the privileges of the Statist middle

class while scrupulously ignoring the more radical political implications of the

restoration of Irish. The situation was not helped by the fact that many

language activists themselves were complicit in this class agenda and were

largely content between dinner dances to pass endless motions in the polite wars

of bureaucratic attrition. As Máirtín Ó Cadhain once observed:

[…] resolutions, delegations and goodwill can no longer billhook their way

through the rank undergrowth of Government subsidiaries, the impenetrable jungle

of semi-Ministries, semi-demi-Ministries, shadow Ministries, state companies,

boards, institutes. [2]

The failure to properly analyze the relation between language politics and power

relations in the society meant that frustrated hectoring rather than direct,

political engagement became the order of the day. It was difficult, in effect,

to look for change if you did not know what needed to be changed. Only when

groups like Misneach and Gluaiseacht Cearta Sibihialta na Gaeltachta

emerged in the 1960s did Irish-language activism finally move from the bar to

the barricade and make the crucial link to political struggles ‘beyond the

billows’. What Language from Below demonstrates, and this is why it is

such an important book in our present age, is the continuing importance of

collective social action. There would be no Irish-language schools, no

Irish-language radio stations, no Irish-language television, no Irish-language

press, if the Irish State had been expected to deliver on any or all of these

things. On the contrary, one of the first, major obstacles systematically

encountered by language activists in all of their campaigns was the obdurate

refusal of the State to take them seriously or to make concessions. It was the

concerted, continuous actions of groups of politically aware activists that

eventually ensured that change came about and that initiatives bore fruit. In

this respect, their actions challenge the more general political torpor of late

modernity with its general suspicion of the value of political solidarity for

social change. It was people acting together taking legal and political risks

(change almost invariably involved breaking the law which in itself says much

about the nature of our laws) that made things happen not polite petitions to

indifferent functionaries. Paradoxically, as Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin

demonstrates, it was by moving away from traditional cultural nationalism that

activists got the State to take part of its avowedly nationalist project

seriously. Rather than simply invoking the house gods of Faith and Fatherland,

the placing of Irish within a global rights dis-course shifted the ground of

argument and wrong footed the doughty warriors of pluralism (which came to mean

everything except Irish).

Commenting on the great upsurge in critical thinking in the 1960s and 1970s,

Terry Eagleton claims that, ‘it seems fair to say that much of the new

cultural theory was born out of an extraordinarily creative dialogue with

Marxism.’ [3] The difficulty is the origins of the dialogue are more often

than not forgotten and ‘culture’ itself, as Eagleton points out, becomes a

substitute for and not a way to explain politics. Language from Below is

therefore refreshingly new and innovative in its re-opening of that dialogue

with Marxist critical writings on language and society. The critical

conversation is all the more important in that the formidable conservatism of

the academy in post-independence Ireland meant that even when the dialogue was

taking place elsewhere, Ireland remained largely silent or contented itself with

philological musings on the copiousness of the copula. A conservative distaste

for theory (other than its own, of course) can be matched by a radical distrust

of theory. Too often, in the Irish-language movement and elsewhere in Irish

civil society, a kind of desperate sloganeering has seduced progressive elements

as if shallow phrases (‘No Blood for Oil’/Ní Tír gan Teanga) could ever become a

substitute for deep thought.

Language from Below is precisely the kind of engaged and engaging

analysis which is necessary if Irish is to play a central role in transformative

and socially advanced politics in Ireland. Unless there is sustained attention

given to the basic concepts that inform political action in the area of

language, then we are condemned to the inarticulacy of the rant or the tragedy

of unwanted outcomes. One outcome, which is generally given rather than desired,

is the post-colonial condition itself. However, as Máirín Nic Eoin has pointed

out, post-colonial criticism has often been loath to address questions of

language except in the most general of terms and in the case of Ireland with one

or two honourable exceptions usually comes to bury Irish rather than to praise

it. In describing the findings of her research, Nic Eoin states:

Féachfar ar an aitheantas an-teoranta a thugann léann idirnáisiúnta an

iarchoilíneachais do thábhacht teangacha dúchais ar nós na Gaeilge agus

scrúdófar easnamh nó ionad fíor-imeallach na Gaeilge i gcuid na hÉireann de

léann an iarchoilíneachais.

[We will

examine the very limited attention paid by international postcolonial studies to

the importance of native languages like Irish and we will examine the absence or

the very marginal position of Irish in the Irish branch of postcolonial studies

(translation).][4]

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is particularly aware of the dangers of a body of

thought which can end up marginalising the very object of its analysis. He draws

parallels with the work of many other writers and thinkers from post-colonial

societies in his bid to think through the implications of colonial influences on

attitudes to language in Ireland and language is, of course, central to how he

conceives of Irish culture, society and economy. There is no sense in which he

sees himself as primarily an Undertaker with Attitude, content to do the decent

thing as Irish is dispatched to the graveyard of the nineteenth century and

Anglophone critics are allowed to enjoy the Gaelic Wake unhindered by anything

as untoward as a living language.

When Herodotus of Halicarnassus told his readers (or rather his listeners) what

was the purpose of his Histories, he said that it was so that, ‘human

achievements may not become forgotten in time, and great and marvellous deeds –

some displayed by Greeks, some by barbarians – may not be without their glory;

and especially to show why two peoples fought each other.’ [5] In writing

the history of language restoration from a broadly sympathetic perspective, the

tendency can be to dwell on ‘great and marvellous deeds’ and explain away all

language conflict in terms of ‘why two peoples fought each other’ (Outing the

Brits). Neither the obituary mode nor the pieties of propaganda do much to

advance our understanding of how language battles have been fought in Ireland

and more importantly how the internal class dynamic within Irish society itself

in the twentieth century has affected attitudes towards language and policies

designed to promote or further its use in society. To this end, the chapters

devoted to the history of language policy are invaluable in offering the reader

a theoretically informed and politically astute reading of the various forces

which combined to effect changes in public policy. Not only do these chapters

properly contextualise what has happened to date in language politics in Ireland

but they also provide a highly useful framework for any future thinking about

language planning and language in society on the island.

In opening up the language situation in Ireland to theoretical speculation from

elsewhere, Language from Below shows how elsewhere has much to learn from

the experience, for better and for ill, of the Irish. As the world faces into

the prospect of linguacide on an unprecedented scale, the local lessons of Irish

have global significance. As more and more languages are forced into extinction

or are increasingly minoritized by a small clutch of major languages, then how

societies or governments or communities try to deal with these pressures is of

importance to every inhabitant on the planet who sees language as an inalienable

right rather than as an optional extra. The fact that the major language Irish

has to contend with is English further adds to the interest of the specific

linguistic situation as English features prominently in fears about the future

cultural and linguistic diversity of the globe. Analyses that marry detailed

theoretical reflection with extended considerations of actual historical and

current practice are, therefore, particularly helpful in exploring how we might

best ensure that peoples everywhere are allowed to speak their difference.

Our century has started more in terror than in triumph. The ruins of the Berlin

Wall were a cause for celebration, the ruins of the Twin Towers and Fallujah a

reason for despair. The planet continues to go deeper and deeper into ecological

debt. It is thus easy to become despondent in the context of the brutal

authoritarianism of the market and the criminalisation of all dissent but

Language from Below is above all to do with change and possibility. It is a

book which demonstrates how solidarity still matters and how ultimately Babel’s

failure is humanity’s greatest achievement.

Professor Michael Cronin

Director, Centre for Translation and Textual Studies,

Dublin City University

Notes:

[1] William O’Brien, ‘The Influence of the Irish Language’, Irish Ideas (London:

Longman, Green and Co., 1893), p. 65.

[2] Máirtín Ó Cadhain, ‘Irish Above Politics’, Gaelic Weekly, 7 March

1964, p. 2.

[3] Terry Eagleton, After Theory (London: Penguin, 2003), p. 35.

[4] Máirín Nic Eoin, Trén bhFearann Breac: An Díláithriú Cultúir agus

Nualitríocht na Gaeilge (Baile Átha Cliath: Cois Life, 2005, p. 18.

[5] Herodotus, The

Histories, trans. Aubrey de Sélincourt (London: Penguin, 1996).

|