|

Other works

Lost Dreams

Series of paintings by

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin

http://gaelart.net

The following series of paintings

consists of portraits of Irish radical / revolutionary leaders covering

the last 300 years. This year is the 90th anniversary of the Easter

Rising leading many to discuss the implications of the 100th anniversary

in 2016. It is an interesting coincidence that the year 2016 will also

be the 400th anniversary of the death of Hugh O'Neill, Earl of Tyrone.

In terms of the struggle against colonialism the year 1616 marked the

end of the beginning with the Flight of the Earls while the Easter

Rising marked the beginning of the end.

The idea of this series is to

explore Irish history in visual way, to re-present well-known Irish

figures not as strict historical paintings but more of a modern

interpretation of their lives and their times. There are notable

exceptions in the series, such as Daniel O'Connell who was essentially a monarchist

and very much looked after his class interests. For example, O'Connell 'cherished a

romantic attachment for his "darling little Queen" (Victoria)' and when

he took his seat as a supporter of the Whig Government in the House of

Commons 'voted against a proposal to shorten the hours of child labour

in factories' in 1838. [See P. Berresford, Ellis, A History of the

Irish Working Class. London, Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1972, pps

100 and 104/5]. Thus the following series concentrates on those leaders

who were revolutionary and progressive and who were concerned for the

ordinary people of Ireland.

One artist who very successfully

painted the history of the people of his country was the Mexican artist

Diego Rivera who made many murals and paintings covering social and

political issues of his time. The following work is an attempt to put

forward and remind Irish people of their radical history in a similar

way.

Part 2 : 1900s - Present Day

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 70cm]

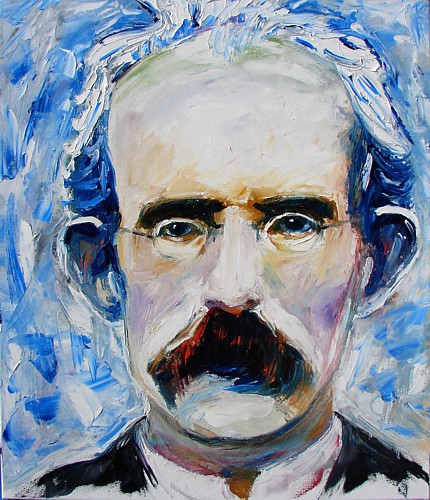

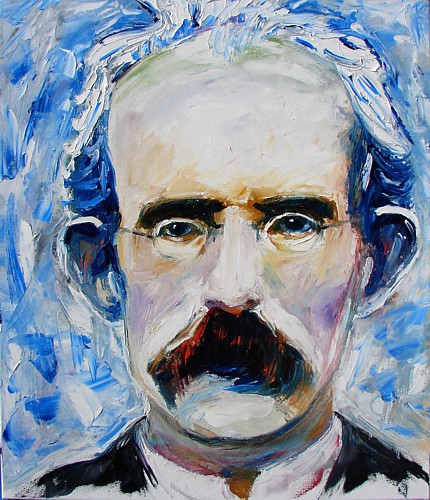

Thomas Clarke (1857-1916)

Thomas James Clarke (March 11, 1857 - May 3, 1916) was born in 1857 on

the Isle of Wight, though his family soon moved to Dungannon, County

Tyrone, Ireland. At the age of 18 he joined the Irish Republican

Brotherhood (IRB) and in 1883 he was sent to London to blow up London

Bridge as part of the dynamiting campaign advocated by Jeremiah

O'Donovan Rossa, one of the IRB leaders exiled in the United States.

Clarke was quickly captured and subsequently served 15 years in

Pentonville Prison. Following his release in 1898 he married Kathleen

Daly (21 years his junior), whose uncle, John, he had met in prison.

Together they emigrated to America, where Clarke worked for the Clan na

Gael under John Devoy. In 1907 he returned to Ireland where he opened a

tobacco shop in Dublin and immersed himself in the IRB which was

undergoing a substantial rejuvenation under the guidance of younger men

such as Bulmer Hobson and Denis McCullough.

In 1915 Clarke and MacDermott established the Military Committee of the

IRB to plan what later became the Easter Rising. The members were Pearse,

Ceannt, and Joseph Plunkett, with Clarke and MacDermott adding

themselves shortly thereafter. When an agreement was reached with James

Connolly and the Irish Citizen Army in January, 1916, Connolly was also

included on the committee, with Thomas MacDonagh added at the last

minute in April. Clarke was stationed in the headquarters at the General

Post Office at Dublin during the events of Easter Week, where command of

the rebel forces was largely under Connolly. Following the surrender on

April 29, Clarke was held in Kilmainham Jail until his execution by

firing squad on May 3rd at the age of 59. He was the second person to be

executed, following Patrick Pearse.

(wikipedia.org)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 70cm]

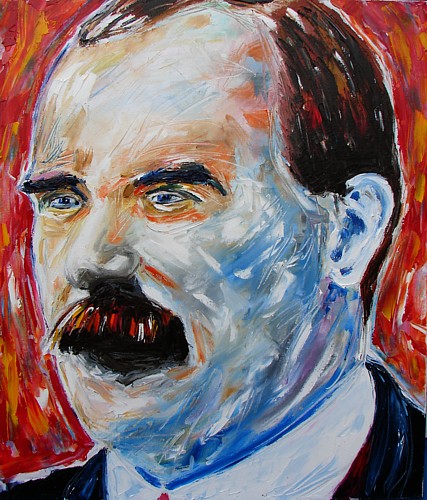

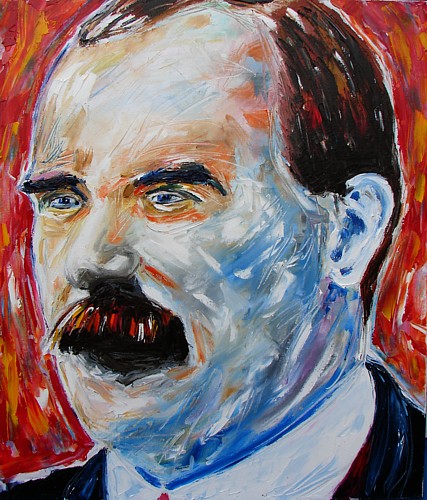

James Connolly (1868-1916)

James Connolly (June 5, 1868 - May 12, 1916) was a

Scottish Irish socialist leader. He was born in Edinburgh, Scotland to

Irish emigrant parents. He left school for working life at the age of

11, but despite this he would become one of the leading left-wing

theorists of his day. Though proud of his Irish background he was also

took a role in Scottish politics.

He is believed to have joined the British Army at the age of 14, and was

stationed in Dublin where he would later meet his wife.

By 1892, he was an important figure in the Scottish Socialist

Federation, acting as its secretary from 1895, but by 1896 he had left

the army and established his Irish Socialist Republican Party (ISRP).

While active as a socialist in Great Britain Connolly was among the

founders of the Socialist Labour Party which split from the Social

Democratic Federation in 1903. He was right hand man to James Larkin in

the Irish Transport and General Workers Union. In 1913, in response to

the Lockout, he founded the Irish Citizen Army (ICA), an armed and

well-trained body of labour men whose aim was to defend workers and

strikers, particularly from the frequent brutality of the Dublin

Metropolitan Police. Though they only numbered about 250 at most, their

goal soon became the establishment of an independent and socialist Irish

nation.

Connolly stood aloof from the leadership of the Irish Volunteers. He

considered them too bourgeois and unconcerned with Ireland's economic

independence. In 1916 thinking they were merely posturing, and unwilling

to take decisive action against Britain, he attempted to goad them into

action by threatening to send his small body against the British Empire

alone, if necessary. This alarmed the members of the Irish Republican

Brotherhood, who had already infiltrated the Volunteers and had plans

for an insurrection that very year. In order to talk Connolly out of any

such rash action, the IRB leaders, including Tom Clarke and Patrick

Pearse, met with Connolly to see if an agreement could be reached. It

has been said that he was kidnapped by them, but this has been denied of

late, and must at some point come down to a matter of semantics. As it

was, he disappeared for three days without telling anyone where he had

been. During the meeting the IRB and the ICA agreed to act together at

Easter of that year.

When the Easter Rising occurred on April 24, 1916, Connolly was

Commandant of the Dublin Brigade, and as the Dublin brigade had the most

substantial role in the rising, he was de facto Commander in Chief.

Following the surrender he was executed by the British for his role,

although he was so badly injured in the fighting that he was unable to

stand for his execution, and was therefore shot in a chair.

(wikipedia.org)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 70cm]

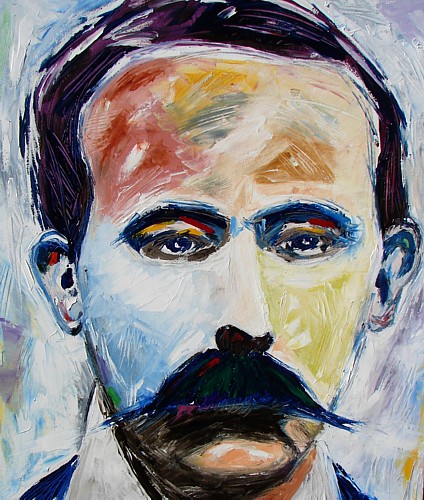

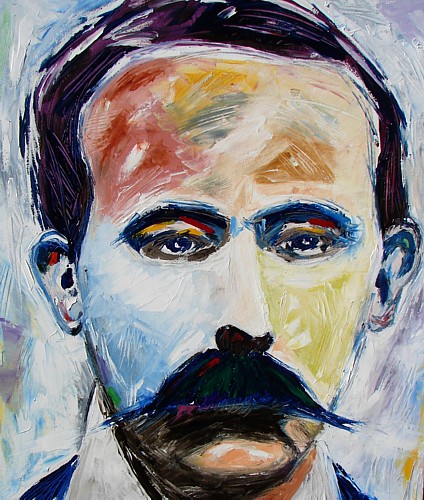

Patrick Pearse (1879-1916)

Patrick Henry Pearse was born in Dublin. His father, a Catholic

convert, was from a Cornish nonconformist family and an

artisan/stonemason, who held moderate home rule views and his mother,

Margaret, was from an Irish-speaking family in County Meath. The

Irish-speaking influence of his aunt Margaret instilled in him an early

love for the Irish language. In 1896, at the age of only sixteen, he

joined the Gaelic League (Conradh na nGaeilge), and in 1903 at the age

of 23, he became editor of its newspaper An Claidheamh Soluis ("The

Sword of Light").

Pearse's earlier heroes were the ancient Gaelic folk heroes such as

Cuchulainn, though in his 30s he began to take a strong interest in the

leaders of past republican movements, such as Theobald Wolfe Tone and

Robert Emmet, both, ironically, Protestant skeptics. As a cultural

nationalist educated by the nationalist, decidedly anti-British Irish

Christian Brothers, like his younger brother Willie, Pearse believed

that language was intrinsic to the identity of a nation. The Irish

school system, he believed, raised Ireland's youth to be good Englishmen

or obedient Irishmen, and an alternative was needed. Thus for him and

other language revivalists, saving the Irish language from extinction

was a cultural priority of the utmost importance. The key to saving the

language, he felt, would be a sympathetic education system. To show the

way, he started his own bilingual school, St. Enda's School (Scoil Éanna)

in Ranelagh, County Dublin, in 1908. Here, the pupils were taught in

both the Irish and English languages.

With the aid of Thomas MacDonagh, Pearse's younger brother Willie Pearse

and other (often transient) academics, it soon proved a successful

experiment. He did all he planned, and even brought students on

fieldtrips to the Gaeltacht in the west of Ireland. Pearse's restless

idealism led him in search of an even more idyllic home for his school.

He found it in the Hermitage, Rathfarnham, where he moved St. Enda's in

1910.

Early in 1914, Pearse became a member of the secret Irish Republican

Brotherhood, an organisation dedicated to the overthrow of British rule

in Ireland and its replacement with a Republic. Pearse was then one of

many people who were members of both the IRB and the Volunteers. When he

became the Volunteers' Director of Military Organisation in 1914 he was

the highest ranking Volunteer in the IRB membership, and instrumental in

the latter's commandeering of the Volunteers for the purpose of

rebellion. By 1915 he was on the IRB's Supreme Council, and its secret

Military Committee, the core group that began planning for a rising

while the Great War raged on the European mainland.

When eventually the Easter Rising did erupt on Easter Monday, 24 April

1916, having been delayed by one day due to fears that the plot had been

uncovered, it was Pearse, as President, who proclaimed a Republic from

the steps of the General Post Office, headquarters of the insurgents, to

a bemused crowd. When, after several days fighting, it became apparent

that victory was impossible, he surrendered, along with most of the

other leaders. Pearse and fourteen other leaders, including his brother

Willie, were court-martialled and executed by firing squad. Thomas

Clarke, Thomas MacDonagh and Pearse himself were the first of the rebels

to be executed, on the morning of 3 May 1916. Pearse was 36 years old at

the time of his death.

(wikipedia.org)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 70cm]

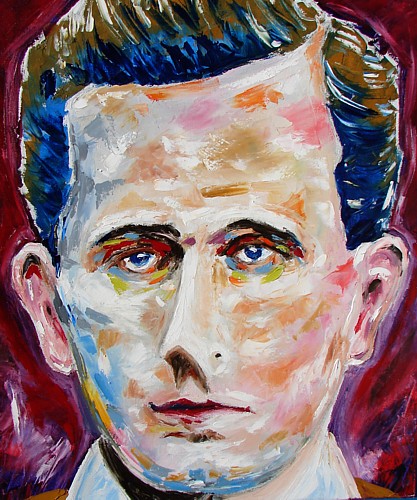

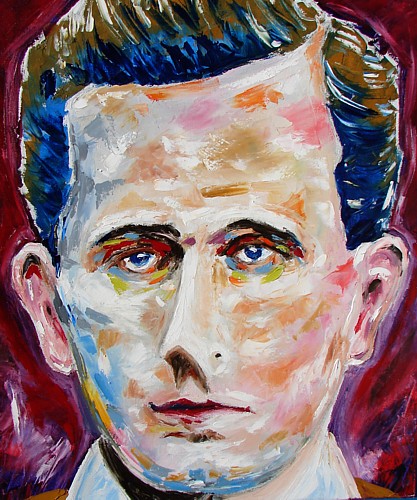

Eamonn Ceannt (1881-1916)

Éamonn Ceannt was born Edward Thomas Kent in Glenamaddy, Ballymore,

County Galway, one of seven children. His father, ironically, was a

member of the Royal Irish Constabulary. When he retired in 1892, he

moved his family to Dublin. It was there that young Edward became

interested in the Irish Ireland movement. He joined the Gaelic League,

adopting the Irish version of his name (Éamonn), and becoming a master

of the uilleann pipes, even putting on a performance for Pope Pius X. He

was employed as an accountant for the Dublin Corporation.

Sometime around 1913 he joined the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and

later was one of the founding members of the Irish Volunteers. As such

he was important in the planning of the Easter Rising of 1916, being one

of the original members of the Military Committee and thus one of the

seven signatories of the Easter Proclamation. He was made commandant of

the 4th Battalion of the Volunteers, and during the Rising was stationed

at the South Dublin Union, with more than a hundred men under his

command, notably his second-in-command Cathal Brugha, and W.T. Cosgrave.

His unit saw intense fighting at times during the week, but surrendered

when ordered to do so by his superior officer Patrick Pearse. Ceannt was

held in Kilmainham Jail until his execution by firing squad on 8 May

1916, aged 34.

(wikipedia.org)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 70cm]

Sean Mac Diarmada (1884-1916)

Seán MacDermott was born John MacDermott in County Leitrim, where he was

educated by the Irish Christian Brothers. Later in life he adopted the

Irish form of his name: Seán MacDiarmada. In 1908 he moved to Dublin, by

which time he already had a long involvement in several Irish separatist

organizations and cultural, including Sinn Fein, the Irish Republican

Brotherhood, and the Gaelic League. He was soon promoted to the Supreme

Council of the IRB and eventually elected secretary. In 1910 he became

manager of the radical newspaper "Irish Freedom", which he founded along

with Bulmer Hobson and Denis McCullough. He also became a national

organizer for the IRB, and was taken under the wing of veteran Fenian

Tom Clarke. Indeed over the year the two became nearly inseparable.

Shortly thereafter MacDermott was stricken with polio and forced to walk

with a cane.

In November 1913 MacDermott was one of the original members of the Irish

Volunteers, and continued to work effortlessly to bring that

organization under IRB control. In May 1915 MacDermott was arrested in

Tuam, County Galway, under the Defense of the Realm Act for giving a

speech against enlisting into the British Army. He was released in

September, where upon he joined the secret Military Committee of the IRB,

which was responsible for planning the rising. Indeed it was MacDermott

and Clarke who were most responsible for it. Being somewhat crippled,

MacDermott took little part in the fighting of Easter week, but was

stationed at the headquarters in the General Post Office. Following the

surrender, he nearly escaped execution by blending in with the large

body of prisoners, but was eventually recognized and summarily executed

by firing squad on May 12 at the age of 33.

(wikipedia.org)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 70cm]

Joseph Plunkett (1887-1916)

Joseph Mary Plunkett (21 November 1887 - 4 May 1916) was an Irish

nationalist, poet, and leader of the Easter Rising in 1916. His father,

George Noble Plunkett, was a papal count and curator of the National

Museum, although his father's cousin, a Protestant named Horace Plunkett

was a Unionist who sought to reconcile both sides, but instead witnessed

his own home burned down during the Anglo-Irish War. At a young age

Plunkett was stricken with tuberculosis, and spent part of his youth in

the warmer climates of the Mediterranean and north Africa. He studied at

the Jesuit College, Stonyhurst College, in Lancashire, and acquired some

military knowledge from the Officers' Training Corps there. Throughout

his life, Joseph Plunkett took an active interest in Irish heritage and

the Irish language. He joined that Gaelic League, and took on as a tutor

Thomas MacDonagh, with whom he formed a lifelong friendship. The two

were both poets with an interest in theater, and both were early members

of the Irish Volunteers, joining their provisional committee.

Sometime in 1915 Joseph Plunkett joined the Irish Republican

Brotherhood, and soon after was sent to Germany to meet with Roger

Casement who was negotiating with the German government on behalf of

Ireland. Plunkett successfully got a promise of a German arms shipment

to coincide with the rising.

Plunkett was one of the original members of the IRB Military Committee

that was responsible for planning the rising, and it was largely his

plan that was followed. As such he may be held partially responsible for

the military disaster that ensued, though one should realize that in the

circumstances any plan was bound to fail. Shortly before the rising was

to begin, Plunkett was hospitalized following a turn for the worse in

his health. He had an operation on his neck glands days before Easter

and had to struggle out of bed to take part in what was to follow. Still

bandaged, he took his place in the General Post Office with several

other of the rising's leaders such as Patrick Pearse and Tom Clarke,

though his health prevented him from being terribly active. His

energetic aide de camp was Michael Collins. Following the surrender

Plunkett was held in Kilmainham Gaol, and faced a court martial. Hours

before his execution by firing squad at the age of 28, he was married in

the prison chapel to his sweetheart Grace Gifford, a Protestant convert

to Catholicism, whose sister, Muriel, had years before also converted

and married his best friend Thomas MacDonagh, who was also executed for

his role in the Easter Rising.

(wikipedia.org)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 70cm]

Thomas MacDonagh (1878-1916)

MacDonagh was born in Cloughjordan, County Tipperary. Throughout his

life he had a keen interest in Irish heritage and the Irish language. He

moved to Dublin where he joined the Gaelic League, soon establishing

strong friendships with such men as Eoin MacNeill and Patrick Pearse.

His friendship with Pearse and his love of Irish led him to join the

staff of Pearse's bilingual St. Enda's School upon its establishment in

1908, taking the role of teacher and Assistant Headmaster. Though

MacDonagh was essential to the school's early success, he soon moved on

to take the position of lecturer in English at the National University.

MacDonagh remained devoted to the Irish language, and in 1910 he became

tutor to a younger member of the Gaelic League, Joseph Plunkett. The two

were both poets with an interest in the Irish Theatre, and formed a

lifelong friendship. In 1912 he married Muriel Gifford, a Protestant who

converted to Catholicism; their son, Donagh, was born later that year.

In 1913 both MacDonagh and Plunkett attended the inaugural meeting of

the Irish Volunteers and were placed on its Provisional Committee. He

was later appointed commandant of Dublin's 2nd battalion, and eventually

made commandant of the entire Dublin Brigade. Though originally more of

a constitutionalist, through his dealings with men such as Pearse,

Plunkett, and Sean MacDermott, MacDonagh developed stronger republican

beliefs, joining the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB), probably during

the summer of 1915. Around this time Tom Clarke asked him to plan the

grandiose funeral of Jeremiah O'Donovan Rossa, which was a resounding

propaganda success. Though credited as one of the Easter Rising's seven

leaders, MacDonagh was a late addition to that group. He didn't join the

secret Military Council that planned the rising until April 1916, weeks

before the rising took place. The reason for his admittance at such a

late date is uncertain.

Still a relative newcomer to the IRB, men such as Clarke may have been

hesitant to elevate him to such a high position too soon, which begs the

question; why admit him at all? His close ties to Pearse and Plunkett

may have been the cause, as well as his position as commandant of the

Dublin Brigade (though his position as such would later be superseded by

James Connolly as commandant-general of the Dublin division).

Nevertheless, MacDonagh was a signatory of the Easter Proclamation.

During the rising, MacDonagh's battalion was stationed at the massive

complex of Jacob's Biscuit Factory. On the way to this destination the

battalion encountered the veteran Fenian, John MacBride, who on the spot

joined the battalion as second-in-command, and in fact took over much of

the command throughout Easter Week, although he had had no prior

knowledge and was in the area by accident. As it was, despite

MacDonagh's rank and the fact that he commanded one of the strongest

battalions, they saw little fighting, as the British Army easily

circumvented the factory as they established positions in central

Dublin. MacDonagh received the order to surrender on April 30, though

his entire battalion was fully prepared to continue the engagement.

Following the surrender, MacDonagh was court martialled, and executed by

firing squad on 3 May 1916, aged 38.

(wikipedia.org)

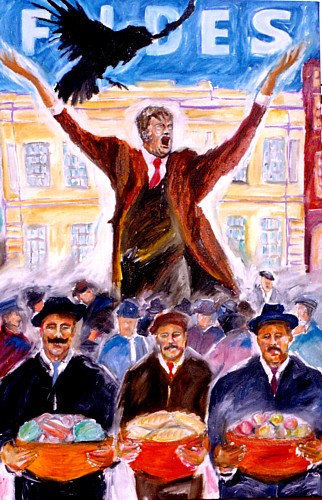

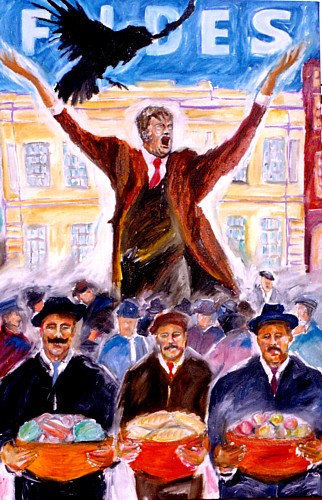

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 90cm]

(Sold)

James Larkin (1876-1947)

James (Big Jim) Larkin (1874-1947), an Irish trade union leader and

socialist activist, was born in Liverpool, England on 28 January 1874,

of Irish parents. Growing up in poverty, he had little formal education

and began working in a variety of jobs while still a child before

becoming a full-time trade union organiser in 1905. He moved to Ireland

in 1907, where he founded the Irish Transport and General Workers'

Union, the Irish Labour Party, and later the Workers' Union of Ireland.

In early 1913 Larkin achieved some notable successes in industrial

disputes in Dublin, making frequent recourse to sympathetic strikes and

blacking of goods. Two major employers remained non-union firms and a

target of Larkin's organising ambitions: Guinness and the Dublin United

Tramway Company. Guinness staff were well-paid and enjoyed generous

benefits from a paternalistic management, and as a result they showed

little interest in trade unions. This was far from the case on the

tramways. The chairman of the Dublin United Tramway Company,

industrialist and newspaper proprietor William Martin Murphy, was

determined not to allow the ITGWU to unionise his workforce. On 15

August he dismissed forty workers he suspected of ITGWU membership,

followed by another 300 over the next week. On 26 August the tramway

workers officially went on strike. Led by Murphy, over four hundred of

the city's employers retaliated by requiring their workers to sign a

pledge not to be a member of the ITGWU and not to engage in sympathetic

strikes.

The resulting industrial dispute was the most severe in Ireland's

history. Employers in Dublin engaged in a lockout of their workers when

the latter refused to sign the pledge, employing blackleg labour from

Britain and elsewhere in Ireland. Dublin's workers, amongst the poorest

in the then United Kingdom, were forced to survive on generous but

inadequate donations from the British Trades Union Congress (TUC) and

other sources in Ireland, distributed by the ITGWU. For seven months the

lockout affected tens of thousands of Dublin's workers and employers,

with Larkin portrayed as the villain by Murphy's three main newspapers,

the Irish Independent, the Sunday Independent and the Evening Herald.

Other leaders in the ITGWU at the time were James Connolly and William

X. O'Brien, while influential figures such as Pádraig Pearse, Countess

Markievicz and William Butler Yeats supported the workers in the

generally anti-Larkin media. The lockout eventually concluded in early

(1914) when the calls for a sympathetic strike in Britain from Larkin

and Connolly were rejected by the British TUC. Although the actions of

the ITGWU and the smaller UBLU were unsuccessful in achieving

substantially better pay and conditions for the workers, they marked a

watershed in Irish labour history. The principle of union action and

workers' solidarity had been firmly established. Perhaps even more

importantly, Larkin's rhetoric, condemning poverty and injustice and

calling for the oppressed to stand up for themselves, made a lasting

impression.

In September 1923 Larkin formed the Irish Worker League (IWL), which was

soon afterwards recognised by the Communist International (the Comintern)

as the Irish section of the world communist movement. In 1924 Larkin

attended the Comintern congress and was elected to its executive

committee. However, the League was not organised as a political party,

never held a general congress and never succeeded in being politically

effective. Its most prominent activity in its first year was to raise

funds for republican civil war prisoners. In the September 1927 general

election, Larkin ran in North Dublin and was elected. This was to be the

only time that a self-proclaimed communist was elected to Dáil Éireann.

However, as a result of a libel award against him won by William

O'Brien, which he had refused to pay, he was an undischarged bankrupt

and could not take up his seat.

Larkin was unsuccessful in his attempts in the following years to gain a

position as a commercial agent in Ireland for the Soviet Union, and this

may have contributed to his disenchantment with the communist cause. The

Soviets, for their part, were increasingly impatient with his

ineffective leadership. From the early 1930s Larkin drew away from the

Soviet Union. While in the 1932 general election he stood without

success as a communist, in 1933 and subsequently he ran as "Independent

Labour". During this period he also engaged in a rapprochement with the

Catholic Church. In 1936 he regained his seat on Dublin Corporation. He

then regained his Dáil seat in the 1937 general election but lost it

again the following year. James Larkin died in his sleep on 30 January

1947. His funeral mass was celebrated by the Catholic Archbishop of

Dublin, John Charles McQuaid, and thousands lined the streets of the

city as the hearse passed to Glasnevin Cemetery.

(wikipedia.org)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 70cm]

Countess Markiewicz (1868-1927)

Constance, Countess Markiewicz (4 February 1868 – 15

July 1927), was an Irish politician, nationalist and revolutionary. Born

Constance Georgine Gore-Booth, the elder daughter of baronet and

explorer, Sir Henry Gore-Booth, she lived as a child at the Anglo-Irish

family's ancestral home, Lissadell House in County Sligo in western

Ireland. Constance and her younger sister, Eva Gore-Booth, were close

friends of the Anglo-Irish poet, W. B. Yeats, who frequently visited the

house, and were influenced by his artistic and political ideas.

Constance studied art at the Slade School in London and then in Paris,

where in 1893 she met and married Polish/Ukrainian artist, Count Casimir

Dunin-Markiewicz. They settled in Dublin, Ireland in 1903, where she

became involved in radical politics through the suffragette movement and

in the Irish nationalist movement, joining Sinn Féin in 1908, and

founding the militant nationalist boy scouting movement Fianna Éireann

in 1909.

In 1913, her husband moved to the Ukraine (possibly because of his

wife's activities), and never returned. Shortly thereafter she joined

James Connolly's Irish Citizen Army (ICA), and, though a member of the

landed gentry, she devoted herself to the cause of socialism. As a

member of the ICA she took part in the 1916 Easter Rising, shooting a

British sniper at one point, and was sentenced to death by the British

government. The sentence was commuted to life imprisonment due to her

gender, and she was released under the amnesty of 1917.

In the December 1918 general election, Markiewicz was elected for the

constituency of Dublin St Patrick's as one of 73 Sinn Féin MPs. This

made her the first woman elected to the British House of Commons.

However, in line with Sinn Féin policy, she refused to take her seat.

(In 1919, Nancy Astor was elected to the House of Commons, and on

December 1 became the first female member of the House of Commons who

actually sat in Parliament.) Instead Countess Markiewicz joined her

colleagues assembled in Dublin as the first incarnation of Dáil Éireann,

the unilaterally-declared Parliament of the Irish Republic. She was

re-elected to the Second Dáil in the House of Commons of Southern

Ireland elections of 1921. She also converted to Roman Catholicism some

time after the Easter Rising.

Markiewicz served in as Minister for Labour from April 1919 to January

1922, in the Second Ministry and the Third Ministry of the Dáil. Holding

cabinet rank from April to August 1919, she became the first Irish

female Cabinet Minister. She was the only female cabinet minister in

Irish history until 1979 when Máire Geoghegan-Quinn was appointed to the

then junior cabinet post of Minster for the Gaeltacht for Fianna Fáil.

Markiewicz left government in January 1922 along with Eamon de Valera

and others in opposition to the Anglo-Irish Treaty. She fought actively

for the Republican cause in the Irish Civil War, and joined Fianna Fáil

on its foundation in 1926. She was not elected in the Irish general

election of 1922 but was returned in the 1923 election for the Dublin

South constitency. In common with other Republican candidates, she did

not take her seat. In the June 1927 election, she was re-elected to the

5th Dáil as a candidate for the new Fianna Fáil party, which was pledged

to return to Dáil Éireann, but died only five weeks later, before taking

her seat.

She died at the age of 59, on 15 July 1927, after a short illness, and

is buried in Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, Ireland. The by-election for

her Dáil seat in Dublin South was held on 24th August and won by the

Cumann na nGaedhael candidate Thomas Hennessy.

(wikipedia.org)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 70cm]

(Sold)

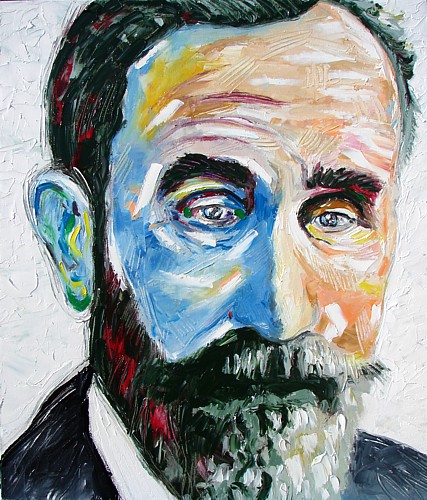

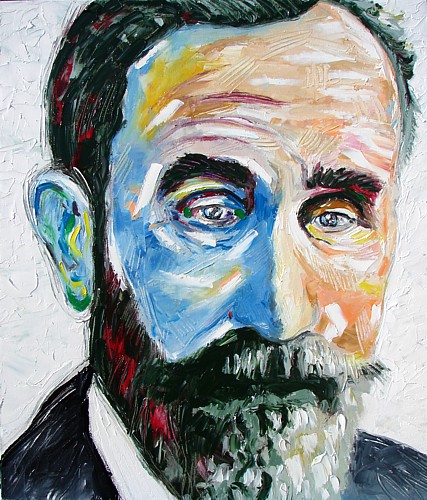

Roger Casement (1864-1916)

Casement was born in Sandycove, near Dublin to a Protestant father and a

Roman Catholic mother, who died when he was a baby. By the time he was

ten, his father was also dead, and he was afterwards raised by

Protestant paternal relatives in Ulster.

Casement went to Africa for the first time in 1883, at the age of only

nineteen, working in Congo Free State for several companies and for King

Léopold II of Belgium's Association Internationale Africaine. While in

Congo, he also met the famous explorer Henry Morton Stanley during the

latter's Emin Pasha Relief Expedition and became acquainted with the

young Joseph Conrad, who was a sailor but not yet a published writer.

In 1892 Roger Casement left Congo to join the Colonial Office in

Nigeria. In 1895 he became consul at Lourenço Marques (now Maputo).

By 1900 he was back in Congo, at Matadi, and founded the first British

consular post in that country. In his dispatches to the Foreign Office

he denounced the mistreatment of indigenous people and the catastrophic

consequences of the forced labour system. In 1903, after the House of

Commons, pressed by humanitarian activists, passed a resolution about

Congo, Casement was charged to make an inquiry into the situation in the

country. The result of his enquiry was his famous Congo Report.

Casement resigned from colonial service in 1912. The following year, he

joined the Irish Volunteers, and became a close friend of the

organisation's chief of staff Eoin MacNeill. When the First World War

broke out in 1914, he attempted to secure German aid for Irish

independence, sailing for Germany via America. The Germans, who were

sceptical of Casement but nonetheless aware of the military advantage

they could gain from an uprising in Ireland, offered the Irish 20,000

guns, 10 machine guns and accompanying ammunition, a fraction of the

amount of weaponry Casement had hoped for.

The German weapons never reached Ireland. The ship in which they were

travelling, a German cargo vessel, the Libau, was intercepted, even

though it had been thoroughly disguised as a Norwegian vessel, Aud Norge.

Casement left Germany in a submarine, the U-19, shortly after the Aud

sailed. Believing that the Germans were toying with him from the start,

and purposely providing inadequate aid that would doom a rising to

failure, he decided he had to reach Ireland before the shipment of arms,

and convince Eoin MacNeill (who he believed was still in control) to

cancel the rising. In the early hours of April 21, 1916, two days before

the rising was scheduled to begin, Casement was put ashore at Banna

Strand in County Kerry. Too weak to travel (he was ill), he was

discovered and subsequently arrested on charges of treason, sabotage and

espionage against the Crown. Following a highly publicized trial, he was

stripped of his knighthood. After an unsuccessful appeal against the

death sentence, he was hanged at Pentonville Prison in London on 3

August 1916, at the age of 51.

(wikipedia.org)

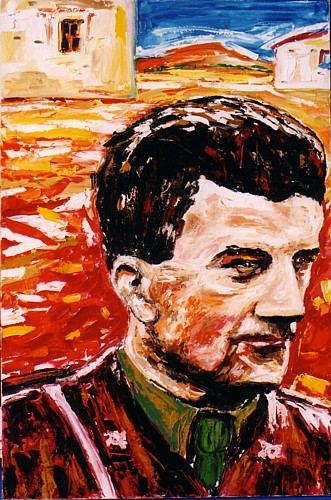

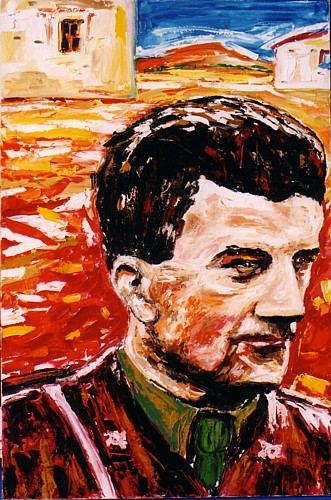

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 90cm]

Frank Ryan (1902-1944)

Frank Ryan attended University College Dublin where he was a member of

the Irish Republican Army (IRA) training corps, but left before

graduating in order to join the IRA's East Limerick Brigade in 1922. He

fought on the Republican side in the Irish Civil War, and was wounded

and interned. In 1933, Ryan, along with George Gilmore and Peadar

O'Donnell, proposed the establishment of a new left-republican

organisation to be called the Republican Congress. This would form the

basis of a mass revolutionary movement appealing to the working class

and small farmers. In late 1936 Frank Ryan travelled to Spain with about

80 men he had succeeded in recruiting to fight in the International

Brigades on the Republican side. He fought in a number of engagements

until he was seriously wounded in March 1937, and returned to Ireland to

recover. He took advantage of the opportunity of his return to launch

another left-republican newspaper, entitled The Irish Democrat. On his

return to Spain, he again served in the war until he was captured by

Nationalist forces in March 1938. He was court-martialled and sentenced

to death. In July 1940 the Abwehr arranged for his "escape", effectively

abducting him and taking him to Berlin, since they considered that a

prominent Irish republican might be useful. The short remainder of Frank

Ryan's life was spent in Germany, marked by ill-health. In January 1943

he suffered a stroke, and died in June 1944.

(wikipedia.org)

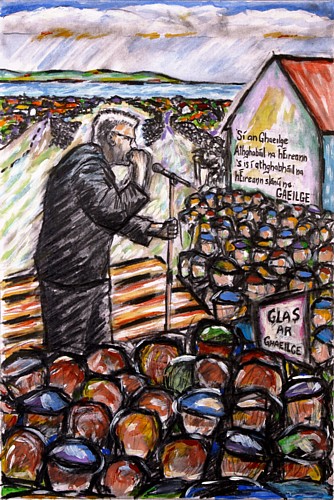

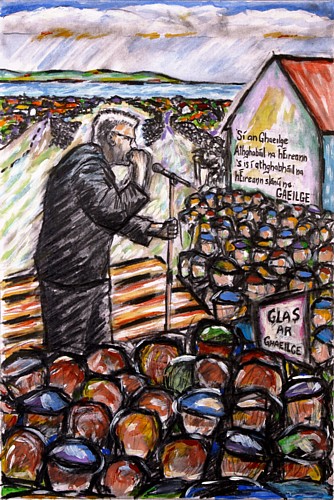

Acrylic and graphite on card / Aicrileach agus

grafít ar chárta [20cm x 30cm] (Sold)

Máirtín Ó Cadhain

(1906 - 1970)

Máirtín Ó Cadhain (1906 - 1970) was one of the most

important Irish language writers of the twentieth century.

Born in Connemara, he studied to be a teacher, but due to his

difficulties with priests and other authority figures, as well as his

social and political commitment, this career turned out to be abortive.

In the nineteen thirties, he participated in the land campaign of the

native speakers, which led to the establishment of the Ráth Cairn neo-Gaeltacht

in County Meath. Subsequently, he was arrested and interned during the

Emergency years on the Curragh internment camp in County Kildare, due to

his involvement in the illegal activities of the Irish Republican Army.

Ó Cadhain's politics were the usual Irish nationalist mix of vague

socialism and social radicalism tempered with a rhetorical

anti-clericalism. However, in his writings concerning the future of the

Irish language he was rather practical about the position of the Church

as a social and societal institution, craving rather for a wholehearted

commitment to the language cause even among Catholic churchmen: as the

Church was there anyway, it would be better that it be a Church happy to

address the believers in the national idiom.

As a writer, Ó Cadhain is universally acknowledged to be a pioneer of

Irish-language modernism. His Irish was the dialect of Connemara -

indeed, he is often accused of an unnecessarily dialectal usage in

grammar and orthography even in contexts where realistic depiction of

Connemara dialect was not called for - but he was happy to cannibalise

other dialects, classical literature and even Scots Gaelic for the sake

of linguistic and stylistic enrichment of his own writings.

Consequently, much of what he wrote is reputedly hard to read for a

non-native speaker.

He was a prolific writer of short stories. His collections of short

stories include Cois Caoláire, An Braon Broghach, Idir Shúgradh agus

Dháiríre, An tSraith Dhá Tógáil, An tSraith Tógtha and An tSraith ar Lár.

He also wrote three novels, of which only Cré na Cille was published

during his lifetime. The other two, Athnuachan and Barbed Wire, appeared

in print only recently. The first two are more or less absurd depictions

of Gaeltacht life; the third one is a linguistic experiment on a par

with James Joyce's Ulysses. He also wrote several political or linguo-political

pamphlets. His political views can most easily be discerned in a small

book about the development of Irish nationalism and radicalism since

Theobald Wolfe Tone, Tone Inné agus Inniu; and in the beginning of the

sixties, he wrote - partly in Irish, partly in English - a comprehensive

survey of the social status and actual use of the language in the west

of Ireland, published as An Ghaeilge Bheo - Destined to Pass.

Due to Máirtín Ó Cadhain's character as Gaelic Ireland's most important

writer and littérateur engagé with frequent difficulties to get his work

edited, new Ó Cadhain titles of hitherto unpublished writings have

appeared at least every two years since the publication of Athnuachan in

the mid-nineties. More is probably still forthcoming.

(wikipedia.org)

Máirtín Ó Cadhain as a student

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás [60cm x 70cm]

(Sold)

Máirtín Ó Cadhain was born and educated in Connemara,

County Galway where he became a school-teacher. In the 1930's he joined

the IRA and lost his teaching post because a local Catholic Bishop

objected to Ó Cadhain's republicanism. He became an IRA Recruiting

Officer in Dublin and is said to have recruited Brendan Behan among

others. In 1938 Ó Cadhain was appointed to the IRA Army Council and

published his first collection of short stories Idir Shúgradh agus

Dáiríre in 1939. Ó Cadhain was interned in the Curragh Internment Camp

from 1940-1945 during which time he taught Irish and Welsh to his fellow

internees, including Michael O'Riordan and Liam Brady.

In 1948 Ó Cadhain published An Braon Broghach and in 1949, what many

consider to be the greatest novel published in Irish in the 20th

century, Cré na Cille. In the same year Ó Cadhain became a translator

for the Oireachtas, translating European literary classics into Irish.

In 1952 Ó Cadhain published Cois Caoláire and in 1956 he joined the

staff of the Department of Modern Irish at TCD. Throughout the 1950's

and 1960's Ó Cadhain retained his interest in politics and was a member

of Wolfe Tone Society and supported the first Republican Club in TCD. In

1967 Ó Cadhain published An tSraith an Lár and in 1969 he was appointed

Professor of Modern Irish at TCD. Ó Cadhain published An tSraith Dá

Tógáil and was created a Fellow of TCD shortly before his death in 1970.

His Selected Poems was published posthumously in 1984.

(searcs-web.com/ocadh.html)

Other works

|