|

matriarchy v patriarchy

nature-based v

anti-nature

|

Resources |

Goddess and the Fall books

1/ Jesus Puzzle: Did Christianity Begin with a Mythical Christ? – 1 Jun

2005

by Earl Doherty (Author)

2/ Nailed: Ten Christian Myths That Show Jesus Never Existed at All – 1

Oct

2010

by David Fitzgerald (Author)

3/ The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype (Princeton Classics) –

4

May 2015 by Erich Neumann (Author)

4/ The Woman's Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects – 11 Feb 1988

by Barbara G. Walker (Author)

5/ Women's Encyclopedia of Myths and Secrets – 1 Aug 1996

by Barbara G. Walker (Author)

6/ The Crone – 1 Feb 1991

by Barbara G. Walker (Author)

7/ Man Made God: A Collection of Essays – 15 Apr 2010

by Barbara G. Walker (Author),? D. M. Murdock (Foreword),

8/ The Chalice and the Blade – 1 Oct 1998

by Riane Eisler (Author)

9/ The Serpent and the Goddess: Women, Religion and Power in Celtic

Ireland –

17 Jan 1991 by Mary Condren (Author)

10/ Suns of God: Krishna, Buddha and Christ Unveiled – 1 Sep 2004

by Acharya S (Author)

11/ Christ in Egypt: The Horus-Jesus Connection – 28 Feb 2009

by D. M. Murdock (Author),? Acharya S (Author)

12/ Christ Conspiracy: The Greatest Story Ever Sold – 1 Sep 1999

by Acharya S (Author)

13/ Who Was Jesus? Fingerprints of the Christ – 15 Oct 2007

by D. M. Murdock (Author)

14/ When God Was a Woman (Harvest/HBJ Book) – 4 May 1978

by Merlin Stone (Author)

15/ The Great Cosmic Mother: Rediscovering The Religion Of The Earth – 7

Nov

1991 by Monica Sjoo (Author),? Barbara Mor (Author)

16/ The Language of the Goddess: Unearthing the Hidden Symbols of

Western

Civilization – 26 Feb 2001 by Marija Gimbutas (Author),? Joseph Campbell

(Author)

17/ The Goddesses and Gods of Old Europe: Myths and Cult Images:

6500-3500 BC

Myths and Cult Images – 8 Mar 1982 by Marija Gimbutas (Author)

18/ The Fall: The Insanity of the Ego in Human History and the Dawning

of a

New Era – 13 Oct 2005 by Steve Taylor (Author)

19/ Saharasia: The 4000 BCE Origins of Child Abuse, Sex-Repression,

Warfare

and Social Violence, In the Deserts of the Old World – 20 May 2011

by James DeMeo (Author)

20/ Memories and Visions of Paradise: Exploring the

Universal Myth of a Lost

Golden Age – 1 Apr 1989 by Richard Heinberg (Author)

21/ The Dark Side of Christian History – 1 Jul 1995

by Helen Ellerbe (Author)

Notes and Quotes

20/ Memories and Visions of Paradise: Exploring the Universal Myth of a

Lost

Golden Age – 1 Apr 1989 by Richard Heinberg (Author)

One of particular appeal is a quotation from Ovid written around 8AD

which

laments humanity's loss of its original Golden condition: "..... And the

land, hitherto a common possession like the light of the sun and the

breezes,

the careful surveyor now marked out with long-drawn boundary lines. Not

only

were corn and needful foods demanded of the rich soil, but men bored

into the

bowels of the earth, and the wealth she had hidden and covered with

Stygian

darkness was dug up, an incentive to evil. And now noxious iron and gold

more

noxious still were produced: and these produced war - for wars are

fought

with both - and rattling weapons were hurled by bloodstained hands."

A matriarchal religion is a

religion that focuses on a goddess or goddesses.[1] The term is most

often used to refer to theories of prehistoric matriarchal religions

that were proposed by scholars such as Johann Jakob Bachofen, Jane Ellen

Harrison, and Marija Gimbutas, and later popularized by second-wave

feminism. In the 20th century, a movement to revive these practices

resulted in the Goddess movement.

The concept of a prehistoric matriarchy was introduced in 1861 when

Johann Jakob Bachofen published Mother Right: An Investigation of the

Religious and Juridical Character of Matriarchy in the Ancient World. He

postulated that the historical patriarchates were a comparatively recent

development, having replaced an earlier state of primeval matriarchy,

and postulated a "chthonic-maternal" prehistoric religion.

Additionally, anthropologist Marija Gimbutas introduced the field of

feminist archaeology in the 1970s. Her books The Goddesses and Gods of

Old Europe (1974), The Language of the Goddess (1989), and The

Civilization of the Goddess (1991) became standard works for the theory

that a patriarchic or "androcratic" culture originated in the Bronze

Age, replacing a Neolithic Goddess-centered worldview.[7

Most modern anthropologists reject the idea of a prehistoric matriarchy,

but recognize matrilineal and matrifocal groups throughout human

history.[9]

Criticism

Debate continues on whether ancient matriarchal religion historically

existed.[11] American scholar Camille Paglia has argued that "Not a

shred of evidence supports the existence of matriarchy anywhere in the

world at any time," and further that "The moral ambivalence of the great

mother Goddesses has been conveniently forgotten by those American

feminists who have resurrected them."[12] In her book The Myth of

Matriarchal Prehistory (2000), scholar Cynthia Eller discusses the

origins of the idea of matriarchal prehistory, evidence for and against

its historical accuracy, and whether the idea is good for modern

feminism.[13]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matriarchal_religion

The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why An Invented Past Will Not Give

Women a Future is a book by Cynthia Eller that seeks to deconstruct the

theory of a prehistoric matriarchy. This hypothesis, she says, developed

in 19th century scholarship and was taken up by 1970s second-wave

feminism following Marija Gimbutas. Eller, a professor of religious

studies at Claremont Graduate University, argues in the book that this

theory is mistaken and its continued defence is harmful to the feminist

agenda.

Eller's book has been criticised for mischaracterising the theories of

Gimbutas and other key anthropologists, labeling them as "matriarchalist"

despite most of these scholars rejecting ideas of matriarchy (female

rulership) in favour of matrifocal or matrilineal societies. In her

critique of Eller's book, feminist historian Max Dashu wrote that Eller

"makes no distinction between scholarly studies in a wide range of

fields and expressions of the burgeoning Goddess movement, including

novels, guided tours, market-driven enterprises. All are conflated all

into one monolithic 'myth' devoid of any historical foundation."[2][3]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Myth_of_Matriarchal_Prehistory

Maxine Hammond (born 1950), known professionally as Max Dashu, is an

American feminist historian, author and artist. Her areas of expertise

include female iconography, mother-right cultures and the origins of

patriarchy.

In 1970, Dashu founded the Suppressed Histories Archives to research and

document women's history and to make the full spectrum of women's

history and culture visible and accessible.[1][2] The collection

includes 15,000 slides and 30,000 digital images.[3][4] Since the early

1970s, Dashu has delivered visual presentations on women's history

throughout North America, Europe and Australia.[

Dashu's decades-long work has focused on women's history around the

world, including Europe, Asia and Africa.[3] Areas of focus include

women shamans and priestesses, witches and the witch trials, folk

religion and pagan European traditions. Her work has cited evidence in

support of egalitarian matrilineages, and she authored a critique of

Cynthia Eller's The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory (2000). Her article

Knocking Down Straw Dolls: A Critique of Cynthia Eller's The Myth of

Matriarchal Prehistory was reprinted in the journal Feminist Theology in

2005.[3][12][13] Dashu has also published in the 2011 anthology

Goddesses in World Culture, edited by Patricia Monaghan.[14]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Max_Dashu

The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State begins with an

extensive discussion of Ancient Society which describes the major stages

of human development as commonly understood in Engels' time. It is

argued that the first domestic institution in human history was not the

family but the matrilineal clan. Engels here follows Lewis H. Morgan's

thesis as outlined in his major book, Ancient Society. Morgan was an

American business lawyer who championed the land rights of Native

Americans and became adopted as an honorary member of the Seneca

Iroquois tribe. Traditionally, the Iroquois had lived in communal

longhouses based on matrilineal descent and matrilocal residence, an

arrangement giving women much solidarity and power. Writing shortly

after Marx’s death, Engels stressed the theoretical significance of

Morgan’s highlighting of the matrilineal clan:

The rediscovery of the original mother-right gens as the stage

preliminary to the father-right gens of the civilized peoples has the

same significance for the history of primitive society as Darwin’s

theory of evolution has for biology, and Marx’s theory of surplus value

for political economy.

—?Engels, Friedrich (1884). "Preface to the Fourth Edition". The Origin

of the Family, Private Property and the State. New York: Pathfinder

Press. pp. 27{{subst:ndash;}}38; the quotation is on p.36.

Primitive communism, according to both Morgan and Engels, was based in

the matrilineal clan where women lived with their classificatory sisters

– applying the principle that "my sister’s child is my child". Because

they lived and worked together, women in these communal households felt

strong bonds of solidarity with one another, enabling them when

necessary to take action against uncooperative males.

Engels added political impact to all this, describing the "overthrow of

mother right" as "the world-historic defeat of the female sex"; he

attributed this defeat to the onset of farming and pastoralism. In

reaction, most twentieth-century social anthropologists considered the

theory of matrilineal priority untenable,[7][8] although during the

1970s and 1980s, a range of feminist scholars often attempted to revive

it.[9] The Morgan-Engels argument that early human kinship was

matrilineal is nowadays widely considered to have been

discredited.[citation needed]

"In recent years, evolutionary biologists, geneticists and

palaeoanthropologists have been reassessing the issues, many citing

genetic and other evidence that early human kinship may have been

matrilineal after all.[10][11][12][13] """

(For a critical survey of the current consensus, see Knight 2008, "Early

Human Kinship Was Matrilineal".[14])

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Origin_of_the_Family,_Private_Property_and_the_State

Knight 2008, "Early Human Kinship Was Matrilineal".[14])

http://radicalanthropologygroup.org/sites/default/files/pdf/class_text_105.pdf

Monsanto’s Violence in India: The Sacred and The Profane

By Colin Todhunter

Global Research, September 30, 2017

Global Research 24 March 2017

https://www.globalresearch.ca/monsantos-violence-in-india-the-sacred-and-the-profane/5581536

According to Kermani, the Vedic deities have deep symbolism and many

layers of existence. One such association is with ecology. Surya is

associated with the sun, the source of heat and light that nourishes

everyone; Indra is associated with rain, crops, and abundance; and Agni

is the deity of fire and transformation and controls all changes. So

much importance was given to trees, that there was also Vrikshayurveda –

an ancient Sanskrit text on the science of plants and trees. It contains

details about soil conservation, planting, sowing, treatment,

propagating, how to deal with pests and diseases and a lot more.

On the other hand, Kermani notes that the Western religions, especially

Christianity, viewed this nature worship as paganism, failing to

recognise the scientific and spiritual basis of the relationship between

man and nature and how this is the only way to sustain ecological

balance.

****************************************

""""Christians were made to turn all their love and adoration for nature

towards their one and only god, who was a jealous god. The elements of

nature then became devoid of all divinity and were left to be conquered

by man.""""

*********************************************

Articles

The People’s Christmas: Art, Tradition and Climate Change

Sacred Trees, Christmas Trees and New Year Trees: a Vision for the

Future

The Origins of Violence? Slavery, Extractivism and War

Sex, Drugs and Rollickin’ Roles: Christmas and Our Ever-Changing

Relationship with Nature

COME, bring with a noise,

My merry, merry boys,

The Christmas log to the firing ;

While my good dame, she

Bids ye all be free ;

And drink to your heart’s desiring.

With the last year’s brand

Light the new block, and

For good success in his spending

On your psaltries play,

That sweet luck may

Come while the log is a-teending.

Ceremonies for Christmas by

Robert Herrick (1591–1674)

(Psaltries: a kind of guitar, Teending: kindling)

No season has so much association with music as

the mid-winter, Christmas celebrations. The aural pleasure

associated with the tuneful music and carols of Christmas has been

reduced in recent years by the over-playing of same in shopping

malls, banks, airports etc. yet it is still enjoyed and the

popularity of choirs has not diminished.

However, the visual depictions of mid-winter,

Christmas celebration have also been popular since the 19th century

through books, cinema and television.

The depictions of Christmas range from religious

iconography through to the highly commercialised red-suited,

rosy-cheeked, rotund Santa Claus.

Yet, between these two extremes of the sombre sacred

and the commercialised secular lies a popular iconography best

expressed in the realm of fine art and illustration.

Down through the centuries the pagan aspects of

mid-winter celebration and Christmas such as the Christmas tree, the

Yule log, wassailing and carol singing along with winter sports such

as ice skating and skiing have been depicted by many different

artists.

These paintings and illustrations are also

beloved for the visual pleasure they afford.

More importantly, they show aspects of Christmas

which are becoming more important now in our time of climate change.

That is, their depictions of our past respect for nature.

In recent times, as we gradually learned to

harness nature for our own ends through developments in science we

also became less and less worried about the vicissitudes of nature.

Our forebears, however, knew all too well hunger

and cold in the depths of winter and in their own religious and

superstitious ways tried to attenuate the worst of winter hardship

through traditions and practices which would ensure a bountiful

proceeding year.

For example, the Christmas Tree is a descendant

of the sacred tree which was respected as a powerful symbol of

growth, death and rebirth. Evergreen trees took on meanings

associated with symbols of the eternal, immortality or fertility

(See my article on Christmas Trees here).

Evergreen boughs and then eventually whole evergreen trees were

brought into the house to ward off evil influences. Burning the Yule

log was an important rite to help strengthen the weakened sun of

midwinter.

The Christmas Tree (1911)

Albert Chevallier Tayler (1862–1925)

Wassailing, or blessing of the fruit trees, is

also considered a form of tree worship and involves drinking and

singing to the health of the trees in the hope that they will

provide a bountiful harvest in the autumn. Mumming has also been

associated with the spirit of vegetation or the tree-spirit and is

believed to have developed into the practice of caroling even though

mumming is alive and well in many places in Ireland and England.

All these nature-based practices seem to have

been banned by the church at different times and then gradually

integrated into church rituals (presumably because the church was

not able to stop them).

Therefore our relationship with nature was

demonstrated through winter activities both inside and outside the

home. Outside activities consisted of ice skating, caroling,

wassailing, bringing home the Yule log and the Christmas tree.

Inside activities consisted of large gatherings

of family and friends eating, drinking and parlour games. The

indulgence of Christmas activities was balanced by an overriding

concern that nature had been propitiated or appeased.

One aspect the many depictions of these activities

have in common is the festive gathering of large groups of people.

Modern depictions of Christmas tend to emphasise the nuclear family

gathered around the Christmas tree with the focus on what Santa

brought for the children. Thus Christmas today is experienced as a

more isolated experience than in the past.

The decline of the nuclear family in recent

decades with single parent families, divorce, cohabitation, etc has

created extended family gatherings more akin to the past village

groupings. Outdoor activities have also declined though one can

still hear carollers singing on occasion, though still common in

city streets.

Many artists of over the years have tried to depict

the essence of Christmas and midwinter traditions (see my article on

midwinter traditions here)

and thus helped to keep them in our consciences.

Let’s look at some of the illustrations and

paintings that depict mid-winter festivities over the centuries.

Carole

Carols

Poetry and song are our earliest records of

Christmas celebrations. According to Clement Miles the word “‘carol’

had at first a secular or even pagan significance: in

twelfth-century France it was used to describe the amorous

song-dance which hailed the coming of spring; in Italian it meant a

ring- or song-dance; while by English writers from the thirteenth to

the sixteenth century it was used chiefly of singing joined with

dancing, and had no necessary connection with religion.”[1]

The word carol itself comes from the Old French

word carole, a circle dance accompanied by singers (Latin: choraula).

Carols were very popular as dance songs and processional songs sung

during festivals. In medieval times the

Church referred to caroling as “sinful traffic” and issued decrees

against it in 1209 A.D. and 1435 A.D.

According to Tristram P. Coffin in his Book of Christmas

Folklore, “For seven centuries a formidable series of

denunciations and prohibitions was fired forth by Catholic

authorities, warning Everyman to ‘flee wicked and lecherous songs,

dancings, and leapings’” (p98).

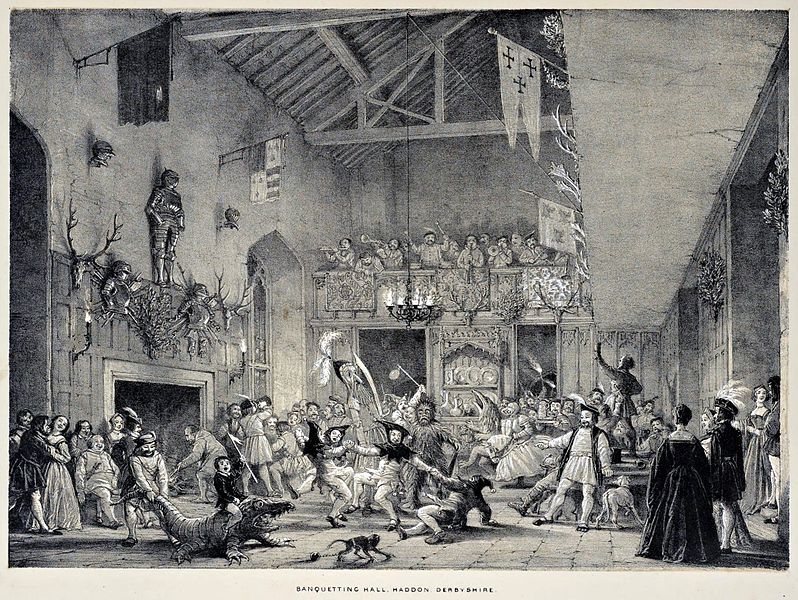

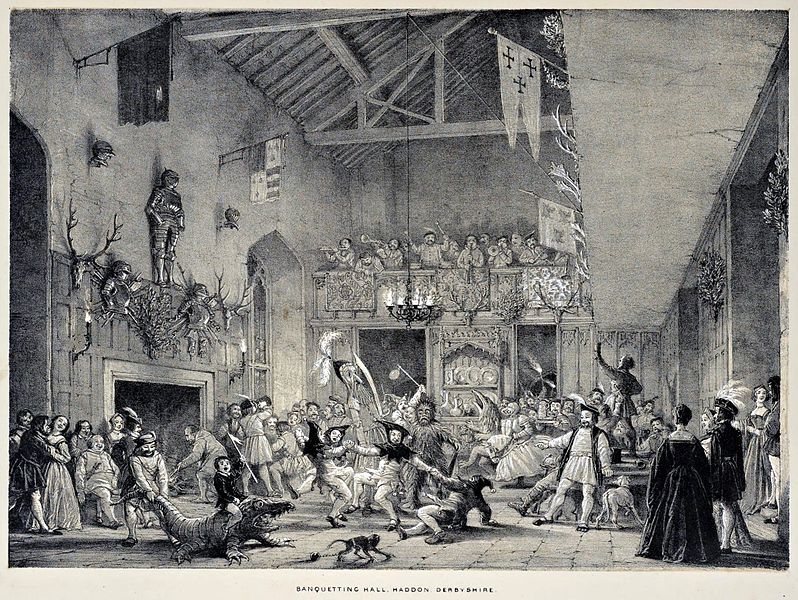

Banqueting Hall

Mumming

The processional

aspects of caroling are linked to mumming, an ancient tradition

which was mentioned in early ecclesiastical condemnations.

During the Kalends

of January a sermon ascribed to St Augustine of Hippo writes that

the heathen reverses the order of things as some of these

‘miserable’ men “are clothed in the hides of cattle; others put on

the heads of beasts, rejoicing and exulting that they have so

transformed themselves into the shapes of animals that they no

longer appear to be men … How vile further, it is that those who

have been born men are clothed in women’s dresses, and by the vilest

change effeminate their manly strength by taking on the forms of

girls, blushing not to clothe their warlike arms in women’s

garments; they have bearded faces, and yet they wish to appear

women.” [2]

The original idea

of wearing the hides of animals, Miles writes, may have sprung “from

the primitive man’s belief ‘that in order to produce the great

phenomena of nature on which his life depended he had only to

imitate them’. [3]

Indeed, in Ireland, mumming is a tradition that

is still going strong.

In a recent article in The Fingal Independent,

Sean McPhilibin notes that

“In North County Dublin the masking would be traditionally made from

straw and would have been big straw hats that cover the face and

come down to the shoulders.” McPhilibin also states that mumming was

“a mid-winter custom that in Ireland and North County Dublin and in

parts of England as well, the masking element is accompanied by a

play. So there’s a play in it with set characters. It’s a play where

the principal action takes place between two protagonists – a hero

and a villain. The hero slays the villain and the villain is revived

by a doctor who has a magical cure and after that happens there’s a

succession of other characters called in, each of whom has a rhyme.

So every character has a rhyme, written in rhyming couplets.[…] The

other thing to say about it is that you find these same type of

characters all across Spain, Portugal, France, Germany, Austria,

Switzerland, over into Slovenia and elsewhere.”

James Frazer, in The Golden Bough, discusses

at length many international examples of people being being

completely covered in straw, branches or leaves as incarnations of

the tree-spirit or the spirit of vegetation, such as Green George,

Jack-in-the-Green, the Little Leaf Man, and the Leaf King.[4]

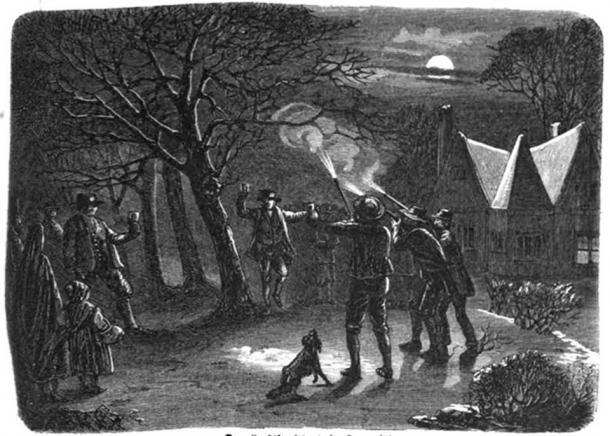

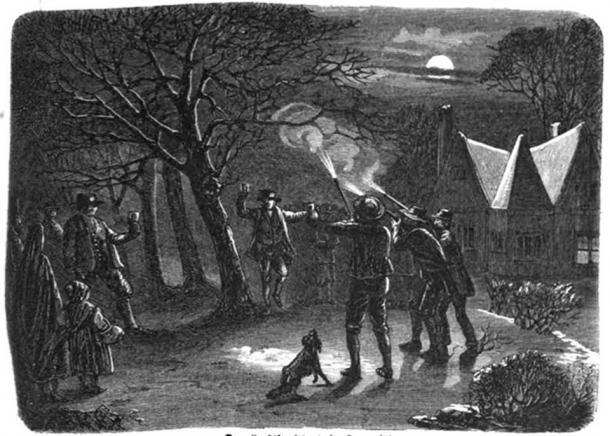

Wassail

Wassail

The word wassail

comes from Old English was hál, related to the Anglo-Saxon

greeting wes þú hál, meaning “be you hale”—i.e., “be

healthful” or “be healthy”.

There are two variations of wassailing: going from

house to house singing and sharing a wassail bowl containing a drink

made from mulled cider made with sugar, cinnamon, ginger and nutmeg,

topped with slices of toast as sops or going from orchard to orchard

blessing the fruit trees, drinking and singing to the health of the

trees in the hope that they will provide a bountiful harvest in the

autumn. They sing, shout, bang pots and pans and fire shotguns to

wake the tree spirits and frighten away evil demons.

The wassail itself

“is a hot, mulled punch often associated with Yuletide, drunk from a

‘wassailing bowl’. The earliest versions were warmed mead into which

roasted crab apples were dropped and burst to create a drink called

‘lambswool’ drunk on Lammas day, still known in Shakespeare’s time.

Later, the drink evolved to become a mulled cider made with sugar,

cinnamon, ginger and nutmeg, topped with slices of toast as sops and

drunk from a large communal bowl.” (See traditional wassail recipe here)

Wassail

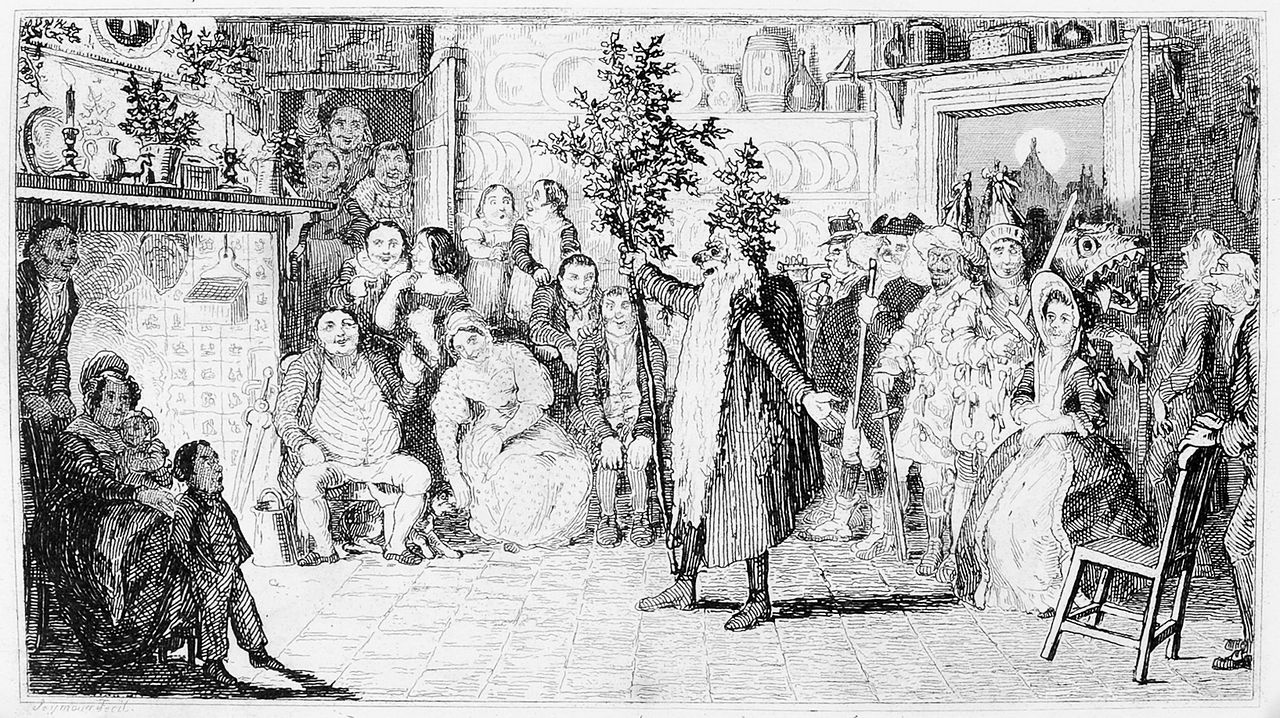

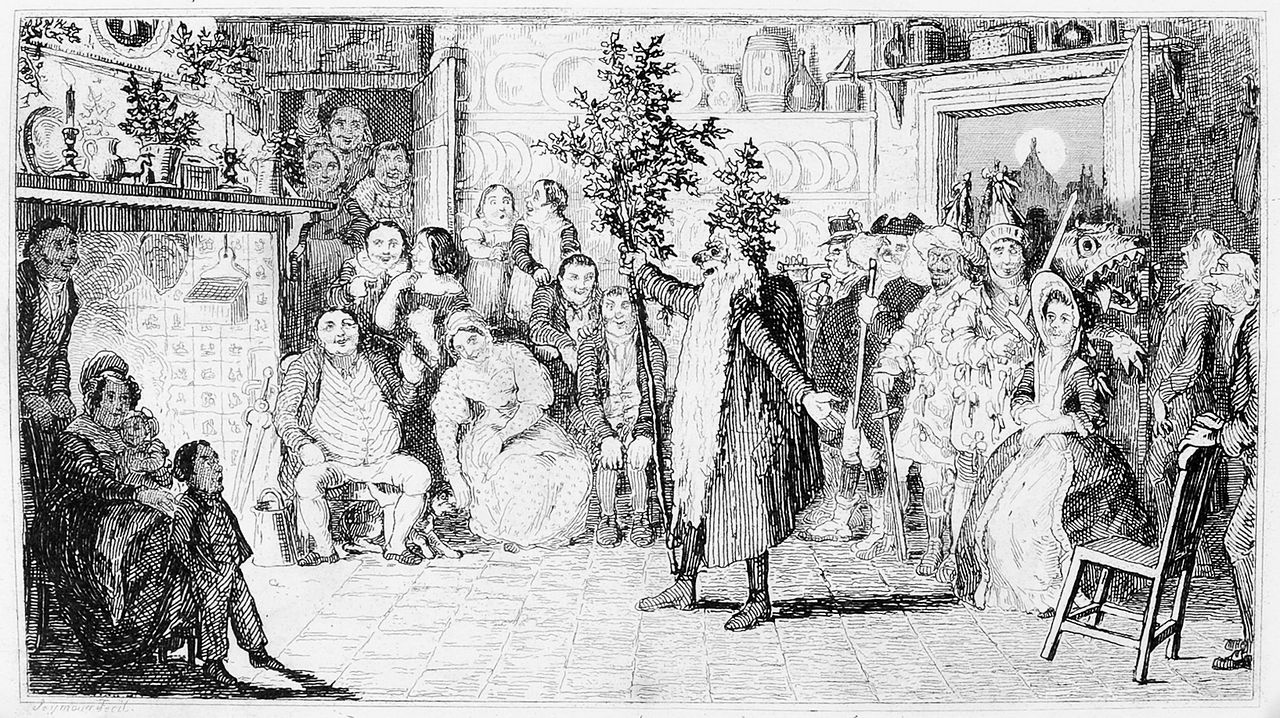

The Lord of Misrule

The Lord of

Misrule was a common tradition that existed up to the early

nineteenth century whereby a peasant or sub-deacon appointed to be

in charge of Christmas revelries, thus the normal societal roles

where reversed temporarily. The Lord of Misrule “would

invite traveling actors to perform Mummer’s plays, he would host

elaborate masques, hold large feasts and arrange the procession of

the annual Yule Log.”

Mummers by Robert Seymour, 1836

The Mount Vernon Yule Log

Jean Leon Gerome Ferris (1863–1930)

The Bean King

During the the Twelfth Night feast a

cake or pie would be served which had a bean baked inside. The

person who got the slice with the bean would be ‘crowned’ the Bean

King with a paper crown and appointed various court officials. A

mock respect would be shown when the king drank and all the party

would shout “the king drinks”. Robert Herrick mentions this in his poem Twelfth

Night: or, King and Queen:

“NOW, now the mirth comes

With the cake full of plums,

Where bean’s the king of the sport here ;

Beside we must know,

The pea also

Must revel, as queen, in the court here.”

Twelfth-night (The King Drinks)

David Teniers the

Younger (1610–1690)

The King Drinks (c.1640)

Jacob (Jacques) Jordaens (1593–1678)

Merry Christmas in the Baron’s Hall (1838)

Daniel Maclise (1806-1870)

Merry Christmas in the Baron’s Hall (1838)

Daniel Maclise’s painting Merry Christmas in the

Baron’s Hall (1838) contains many aspects of the traditional

Christmas festivities. The Lord of Misrule stands in the centre

holding his staff and leading the procession of musicians and

carolers coming down the stairs. Father Christmas, ‘ivy crown’d’,

sits in front of the wassail bowl and is surrounded by mummers (the

Dragon and St George sit side by side) and local people. On the left

side of the picture we see a group of people playing a parlour game

called Hunt the Slipper.

Maclise was influenced by Sir Walter Scott’s poem Marmion:

A Tale of Flodden Field, published in 1808. Marmion is a

historical romance in verse of 16th-century Britain, ending with the

Battle of Flodden in 1513. Marmion has

a section referring to Christmas festivities:

“The wassel round, in good brown bowls,

Garnish’d with ribbons, blithely trowls.

There the huge sirloin reek’d; hard by

Plum-porridge stood, and Christmas pie:

Nor fail’d old Scotland to produce,

At such high tide, her savoury goose.

Then came the merry maskers in,

And carols roar’d with blithesome din;

If unmelodious was the song,

It was a hearty note, and strong.

Who lists may in their mumming see

Traces of ancient mystery;

White shirts supplied the masquerade,

And smutted cheeks the visors made;

But, O! what maskers, richly dight,

Can boast of bosoms half so light!”

(See full text here)

It seems that Maclise was also taken enough by the

poem to pen his own poem about his painting which was published in

Fraser’s Magazine for May in 1838. The poem is titled: Christmas

Revels: An Epic Rhapsody in Twelve Duans and was published under

the pseudonym, Alfred Croquis, Esq. The painting includes over one

hundred figures covering many different traditions of Christmas and

in his poem Maclise describes most of the activities taking place as

some these excerpts from the poem demonstrate:

“Before him, ivied, wand in hand,

Misrule’s mock lordling takes his stand;

[…]

Drummers and pipers next appear,

And carollers in motley gear;

Stewards, butlers, cooks, bring up the rear.

Some sit apart from all the rest,

And these for merry masque are drest;

But now they play another part,

Distinct from any mumming art.

[…]

First, Father Christmas, ivy-crown’d,

With false beard white, and true paunch round,

Rules o’er the mighty wassail-bowl,

And brews a flood to stir the soul:

That bowl’s the source of all their pleasures,

That bowl supplies their lesser measures”

(See full text here)

Winter Landscapes

Winter Landscape near a Village

Hendrick Avercamp (1585

(bapt.) – 1634 (buried))

The Hunters in the Snow (1565)

Pieter Bruegel the

Elder (c.1525-1530–1569)

Winter Landscape with Skaters and Bird Trap (1565)

Pieter Bruegel the

Elder (c.1525-1530–1569)

These famous winter landscape paintings by Pieter

Brueghel the Elder, such as The Hunters in the Snow and Winter

Landscape with Skaters and Bird Trap are all thought to have been

painted in 1565. Hendrick Avercamp also made made many snow and ice

landscapes coinciding with the Little Ice Age. Three particularly

cold intervals have been described as

the Little Ice Age: “one beginning about 1650, another about 1770,

and the last in 1850, all separated by intervals of slight warming”.

Outdoor Activities: Skating, Markets and Fairs

Patineurs au bois de Boulogne (1868)

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919)

Russian Christmas

Leon Schulman Gaspard (1882-1964)

The Christmas Market in Berlin (1892)

Franz Skarbina (1849-1910)

Christmas Fair (1904)

Heinrich Matvejevich Maniser

Nature-Based vs Anti-Nature

Polydore Vergil (c.1470–1555), the Italian humanist scholar,

historian, priest and diplomat, who spent most of his life in

England, wrote this about Christmas: “Dancing, masques, mummeries,

stage-plays, and other such Christmas disorders now in use with the

Christians, were derived from these Roman Saturnalian and

Bacchanalian festivals; which should cause all pious Christians

eternally to abominate them.”[5]

However, Clement Miles takes a more positive view

of these traditions. He writes: “The heathen folk festivals absorbed

by the Nativity feast were essentially life-affirming, they

expressed the mind of men who said “yes” to this life, who valued

earthly good things. On the other hand Christianity, at all events

in its intensest form, the religion of the monks, was at bottom

pessimistic as regards this earth, and valued it only as a place of

discipline for the life to come; it was essentially a religion of

renunciation that said “no” to the world.” [6]

Now we have a religion of consumerism and mass

consumption with Santa Claus as its main protagonist. The one

extreme of the sacred St Nicholas has flipped over to the other

extreme of Santa, the corporate saint. Either way the pious and the

consumer pose no threat to the status quo.

Catharsis

There is no doubt that the Christmas festivities

were used by elites as a form of social catharsis. The Lord of

Misrule and the Bean King, encouraged by raucous mummers and lively

caroling, allowed the lowly to throw off pent-up aggression and feel

what it was like to be in a position of power for a very short

period of time. This brief social revolution was an important part

of midwinter celebrations such as the Roman Kalends and the Feast of

Fools. Libanius (c.314–392 or 393), the fourth century Greek

philosopher, wrote: “The Kalends festival banishes all that is

connected with toil, and allows men to give themselves up to

undisturbed enjoyment. From the minds of young people it removes two

kinds of dread: the dread of the schoolmaster and the dread of the

stern pedagogue. The slave also it allows, so far as possible, to

breathe the air of freedom.” [7]

The survivals of an ancient time when man and nature

were at peace (see article here),

and not enslaved and forced to overexploit our natural resources for

the benefit of the few, were allowed to resurface briefly at the

time of year when the labouring classes were mostly idle and, once

sated, posed little threat. Yet, retaining the memory of past

respectful attitudes towards nature and old traditions of social

upheaval will go a long way towards healing our damaged home into

the future.

Notes:

[1] Clement A. Miles, Christmas Customs and

Traditions: Their History and Significance, Dover Publications,

2017, p47.

[2] Miles, Christmas Customs and Traditions,

p170.

[3] Miles, Christmas Customs and Traditions,

p163.

[4] James Frazer, The Golden Bough, Wordsworth, 1994. See:

The tree-spirit p297, Green George p126, Jack-in-the-Green p128, the

Little Leaf Man p128 and the Leaf King p130.

[5] Hazlitt, W. Carew, Faiths and Folklore of the British Isles,

2 vols, New York: Benjamin Blom, Inc., 1965, p118-19

[6] Miles, Christmas Customs and Traditions, p25.

[7] Miles, Christmas Customs and Traditions, p168.

Sacred Trees, Christmas Trees and New Year Trees: a

Vision for the Future

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin

Trees are a very important part of world culture and

have been at the centre of ideological conflict for hundreds of

years. Over this time they have taken the form of Sacred trees,

Christmas trees and New Year trees. In the current debates over

climate change, trees have an immensely important role to play on

material and symbolical levels both now and in the future. With the

rising awareness of climate change, climate resilience i.e. the

ability to recover from or adjust easily to misfortune or change,

has become the focus of groups from local community action to global

treaties. The planting of trees is an important action that everyone

from the local to the global can engage in. Trees act as carbon

stores and carbon sinks, and on a cultural level they have been used

to represent nature itself the world over.

As symbols, trees have been imbued with different

meanings over time and I suggest here that they should continue to

hold that central role as a prime symbol of our respect for nature,

and not just at Christmas time but the whole year round in the form

of a central community tree for adults and children alike. In an

uncertain future, the absolute necessity of developing a society

that harks back to much earlier forms of engagement with nature in a

sustainable way will have to have a focal point. Trees as important

symbols of our respect for nature have a long and elemental past.

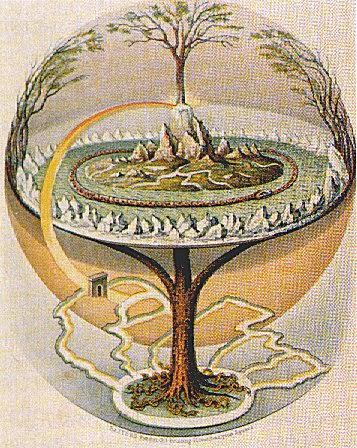

The Tree of Life

From earliest times trees have had a profound effect

on the human

psyche:

“Human beings, observing the growth and death of

trees, and the annual death and revival of their foliage, have often

seen them as powerful symbols of growth, death and rebirth.

Evergreen trees, which largely stay green throughout these cycles,

are sometimes considered symbols of the eternal, immortality or

fertility. The image of the Tree of life or world tree occurs in

many mythologies.”

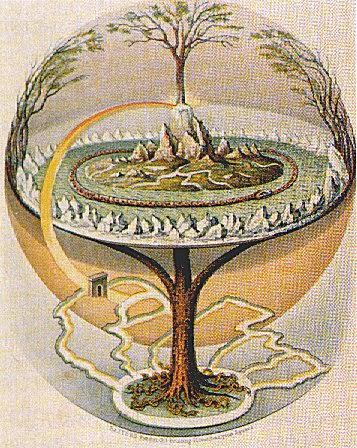

In Norse mythology the tree

Yggdrasil,

“with its branches reaching up into the sky, and roots deep into the

earth, can be seen to dwell in three worlds – a link between heaven,

the earth, and the underworld, uniting above and below. This great

tree acts as an Axis mundi, supporting or holding up the cosmos, and

providing a link between the heavens, earth and underworld.”

Yggdrasil, the World Ash (Norse)

Sacred Trees

However, both Christianity and Islam treated the

worship of trees as idolatry and this led to sacred trees being

destroyed in Europe and most of West Asia. An early representation

of the ideological conflict between paganism (polytheistic beliefs)

and Christianity (resulting in the cutting down of a sacred tree)

can be seen in the manuscript illumination (illustration) of Saint

Stephan

of Perm cutting down a birch tree sacred to the Komi people as part

of his proselytizing among them in the years after 1383.

Stefan of Perm takes an axe to a birch hung with pelts

and cloths that is sacred to the Komi of Great Perm (a medieval

Komi state in what is now the Perm Krai of the Russian

Federation.)

Christian missionaries targeted sacred groves and

sacred trees during the Christianization of the Germanic peoples.

According to the 8th century Vita Bonifatii auctore Willibaldi, the

Anglo-Saxon missionary Saint Boniface and his retinue cut down

Donar’s Oak

(a sacred tree of the Germanic pagans) earlier the same century and

then used the wood to build a church.

“Bonifacius” (1905) by Emil Doepler.

Christmas Trees

Over time the

pagan world tree became christened as a Christmas tree. It was

believed that evil influences were warded off by fir or spruce

branches and “between December 25 and January 6, when evil spirits

were feared most, green branches were hung, candles lit – and all

these things were used as a means of defense. Later on, the

trees themselves were used for the same purpose; and candles

were hung on them. The church retained these old customs, and gave

them a new meaning as a symbol of Christ.’(p20) While there are

records of this practice dating from 1604 of a decorated fir tree in

Strasbourg, it was in Germany that the Christmas tree took hold in

the early 19th century. It

then

“became popular among the nobility and spread to royal courts as far

as Russia.”

Father and son with their dog collecting a tree in the

forest, painting by

Franz Krüger (1797–1857)

The Russian Revolution

In Russia the tradition of installing and decorating

a Yolka (tr: spruce tree) for Christmas was very popular but fell

into disfavor (as a tradition originating in Germany – Russia’s

enemy during World War I) and was subsequently banned by the Synod

in 1916. After the

Russian Revolution in 1917 Christmas celebrations and other

religious holidays were prohibited under the Marxist-Leninist policy

of state atheism in the Soviet Union.

A 1931 edition of the Soviet magazine Bezbozhnik,

distributed by the League of Militant Atheists, depicting an

Orthodox Christian priest being forbidden to cut down a tree for

Christmas

New Year’s trees

Although the Christmas tree was banned people

continued the tradition with

New Year

trees which eventually gained acceptance in 1935: “The New Year tree

was encouraged in the USSR after the famous letter by Pavel

Postyshev, published in Pravda on 28 December 1935, in which he

asked for trees to be installed in schools, children’s homes, Young

Pioneer Palaces, children’s clubs, children’s theaters and cinemas.”

They remain an essential part of the Russian New Year

traditions when

Grandfather Frost, like Santa Claus, brings presents for children to

put under the tree or to distribute them directly to the children on

New Year’s morning performances.

Trees in public places

In many public places around the world Christmas

trees are displayed prominently since the early 20th century. The

lighting up of the tree has become a public event signaling the

beginning of the Christmas season. This is now usual even in small

towns whereby a large fir is chopped down and displayed prominently

in a central part of the town or village. While fir trees are now

grown expressly for sale and display, in the past the cutting down

of whole trees (maien or meyen) was

forbidden: “Because of the pagan origin, and the depletion of

the forest, there were numerous regulations that forbid, or put

restrictions on, the cutting down of fir greens throughout the

Christmas season.”(p20)

Bringing Home the Tree by

Norman Rockwell. 12/18/1920.

Not cutting down trees

However if we look at the origins of sacred trees

the important point was that they were not to be cut down, as

respect for nature took precedence. The cutting down and destruction

of so many trees today has become an important part in the

commercialization of Christmas. However, growing a tree in the

centre of villages, towns and cities as the focal point of our

relationship with nature could be a year round celebration for

adults and children and another aspect of the call for climate

resilience policies the world over. The tree could then be decorated

at Christmas or New Year. The decorations can be removed from the

tree afterwards, allowing it to become a focal point for other

festivities throughout the year. The educational value of this

strategy for children would also be as an object lesson in the

importance of sustainability and conservation.

Celebrating nature by chopping down the material

reality of nature in the form of a tree every year is a

contradiction in terms and could be remedied by encouraging people

to grow trees or buying potted fir trees instead. Our ancestors from

all over the world knew the importance of the balance of nature and

tried to keep that balance through rites and prayers before the

sacred trees. Now, in an era of climate change, rapidly becoming

climate chaos, it is incumbent on us more than ever to develop a new

appreciation and respect for nature and especially for trees as a

primary symbol of that relationship.

The Origins of Violence? Slavery, Extractivism

and War

by Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin / April 27th, 2018

And the land, hitherto a common possession like

the light of the sun and the breezes, the careful

surveyor now marked out with long-drawn boundary lines.

Not only were corn and needful foods demanded of the

rich soil, but men bored into the bowels of the earth,

and the wealth she had hidden and covered with Stygian

darkness was dug up, an incentive to evil. And now

noxious iron and gold more noxious still were produced:

and these produced war – for wars are fought with both –

and rattling weapons were hurled by bloodstained hands.

(Ovid, written around 8 AD which laments humanity’s

loss of its original Golden condition [Ovid

Metamorphoses, Book 1, The Iron Age]).

The privatisation of property, extractivism, the

necessity for food-producing slaves and a warrior class to

sustain and further extend the aims of the elites are all

neatly summed up in this quote from Ovid. What is noticeable

and notable is that over the millennia very little has

changed in substance. We still have today wage slaves,

standing armies, extractivism and industrialised agriculture

that is oriented and controlled according to the aims and

agendas of a warmongering elite. However, it seems that

things were not always thus.

The coming of the Kurgan peoples across Europe from c.

4000 to 1000 BC is believed to have been a tumultuous and

disastrous time for the peoples of Old Europe. The Old

European culture is believed to have centred around a

nature-based ideology that was gradually replaced by an

anti-nature, patriarchal, warrior society. According to the

archeologist and anthropologist, Marija Gimbutas:

Agricultural peoples’ beliefs concerning sterility

and fertility, the fragility of life and the constant

threat of destruction, and the periodic need to renew

the generative processes of nature are among the most

enduring. They live on in the present, as do very

archaic aspects of the prehistoric Goddess, in spite of

the continuous process of erosion in the historic era.

Passed on by the grandmothers and mothers of the

European family, the ancient beliefs survived the

superimposition of the Indo-European and finally the

Christian myths. The Goddess-centred religion existed

for a very long time, much longer than the Indo-European

and the Christian (which represent a relatively short

period of human history), leaving behind an indelible

imprint on the Western psyche.

The Goddess Timeline

A chronological record of archaeological images of women and

goddesses on a uniform time scale from 30,000 BCE to the

present.

Copyright © 2012

Constance Tippett

Gimbutas notes that it was at this time that a relatively

homogeneous pre-Indo-European Neolithic culture in

southeastern

Europe was “invaded and destroyed by horse-riding

pastoral nomads from the Pontic-Caspian steppe (the “Kurgan

culture”) who brought with them violence, patriarchy, and

Indo-European languages”. While this model has been disputed

over the years recent research has broadened and deepened

our understanding of these movements.

In 2015 an international team of researchers conducted a

genetic study which backs the Kurgan

hypothesis, that “a massive migration of herders from

the Yamna culture of the North Pontic steppe (Russia,

Ukraine and Moldavia) towards Europe which would have

favoured the expansion of at least a few of these

Indo-European languages throughout the continent.”

Another disputed aspect of the

hypothesis is the ‘how’- whether “the indigenous

cultures were peacefully amalgamated or violently

displaced.” However, the representations of weapons

engraved in stone, stelae, or rocks appear after the Kurgan

invasions as well as “the earliest known visual images of

Indo-European warrior gods”.

The beginning of slavery is also seen to be linked to these

armed invasions.

According to Riane Eisler, archeological evidence

“indicate that in some Kurgan camps the bulk of the female

population was not Kurgan, but rather of the Neolithic Old

European population. What this suggests is that the Kurgans

massacred most of the local men and children but spared some

of the women who they took for themselves as concubines,

wives, or slaves.”

Gimbutas believed that the pre-Kurgan society of Old Europe

was a “gylanic [sexes were equal], peaceful, sedentary

culture with highly developed agriculture and with great

archtectural, sculptural, and ceramic traditions” which was

then replaced by patriarchy; patrilineality; small scale

agriculture and animal husbandry”, the domestication of the

horse and the importance of armaments (bow and arrow, spear

and dagger).

Not so th’ Golden Age, who fed on fruit,

Nor durst with bloody meals their mouths pollute.

Then birds in airy space might safely move,

And tim’rous hares on heaths securely rove:

Nor needed fish the guileful hooks to fear,

For all was peaceful; and that peace sincere.

Whoever was the wretch, (and curs’d be he

That envy’d first our food’s simplicity!)

Th’ essay of bloody feasts on brutes began,

And after forg’d the sword to murder man.

— Ovid Metamorphoses

Book 14

The idea of a fall, the end of a Golden Age is a common

theme in many ancient cultures around the world. Richard

Heinberg, in Memories and Visions of Paradise,

examines various myths from around the world and finds

common themes such as sacred trees, rivers and mountains,

wise peoples who were moral and unselfish, and in harmony

with nature and described heavenly and earthly paradises.

In another book, The Fall: The Insanity of the Ego in

Human History and the Dawning of a New Era, Steve Taylor

takes a psychological approach to the concept of the Fall

examining what he calls the new human psyche and the Ego

Explosion (which created a lack of empathy between human

beings) and resulted in our alienation from nature while

making us both self and globally destructive.

However, James DeMeo takes a more radical approach in his

book, Saharasia: The 4000 BCE Origins of Child Abuse,

Sex-Repression, Warfare and Social Violence in the Deserts

of the Old World. He believes that climatic changes

caused drought, desertification and famine in North Africa,

the Near East, and Central Asia (collectively Saharasia) and

this trauma caused the development of patriarchal,

authoritarian and violent characteristics.

God creates Man

“Then the LORD God formed a man from the dust of the ground

and breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and the

man became a living being.”(Gen

2:7)

Author unknown, Creation of Adam, Byzantine mosaic in

Monreale, 12th century.

The arrival of violent, enslaving tribes and of a supreme

male deity led to the eventual demise of the female deities

through demotion or destruction of temples and statues.

Over time, the many traditions of pre-patriarchal nature

worship were destroyed (such as cutting down sacred trees)

or eventually assimilated into the new patriarchal religions

(see my

Christmas article). Thus many of the nature-based ideas

of matriarchal religion were turned on their head as the

male deity creates man and Adam gives birth to Eve.

According to Barbara Walker, in The Women’s Encyclopedia

of Myths and Secrets, “usurpation of the feminine power

of birth-giving seems to have been the distinguishing mark

of the earliest gods.” She lists the many ways the male

deities ‘gave birth’; e.g., from the mouth (Prajapati), from

the head or thigh (Zeus), from the penis (Atum), or from the

stomach (Kun) in the section ‘Birth-Giving, Male’.

Adam ‘gives birth’ to Eve

“For man did not come from woman, but woman from man”(1

Corinthians 11:8)

From: Master

Bertram, Grabow Altarpiece, 1379-1383

In Christianity the rulers had a religion that assured

their objectives. The warring adventurism of the new rulers

needed soldiers for their campaigns and slaves to produce

their food and mine their metals for their armaments and

wealth. Thus, Christ was portrayed as Martyr and Master. In

his own crucifixion as Martyr he provided a brave example to

the soldiers and as Master he would reward or punish the

slaves according to how well they had behaved.

Christ as Martyr and Master

Jan van Eyck (before c. 1390 – 9 July 1441)

Crucifixion and Last Judgement diptych, c. 1430–1440.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Christianity, according to Helen Ellerbe:

has distanced humanity from nature. As people came

to perceive God as a singular supremacy detached from

the physical world, they lost their reverence for

nature. In Christian eyes, the physical world became the

realm of the devil. A society that had once celebrated

nature through seasonal festivals began to commemorate

biblical events bearing no connection to the earth.

Holidays lost much of their celebratory spirit and took

on a tone of penance and sorrow. Time, once thought to

be cyclical like the seasons, was now perceived to be

linear. In their rejection of the cyclical nature of

life, orthodox Christians came to focus more upon death

than upon life.

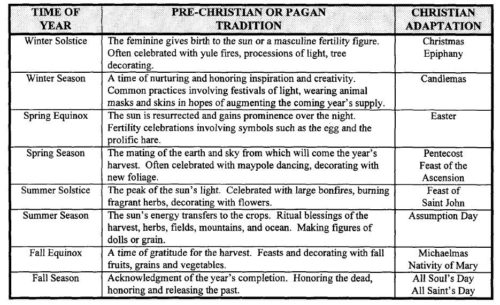

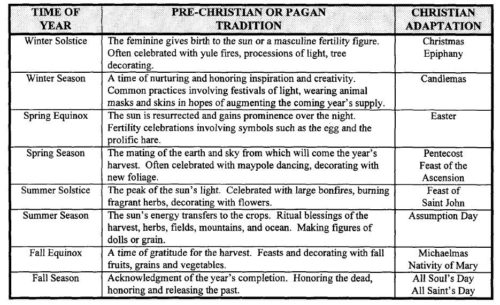

Pagan festivals chart: [From The Dark Side of Christian

History, Helen Ellerbe]

"Then God said, “Let us make humankind in our image,

according to our likeness; and let them have dominion over

the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over

the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and

over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth.”

So God created humankind in his image,

in the image of God he created them;

male and female he created them.

God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and

multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have

dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the

air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.”

"

(Genesis 1:26-28)

According to Fred Magdoff and Chris Williams:

"A rigidly anthropocentric view stemming from biblical

conceptions of the domination of nature and placement of

earth at the service of humans holds that humans are not

only the center and most important part of life on Earth but

sit at the apex of biological development. It is therefore

our right to dominate and exploit the rest of nature. This

view is a complete misunderstanding of the science of

evolution and ecology. However distantly, all living

organisms are connected to one another through evolution. We

are one of an estimated 8.7 million species living on Earth.

Even among mammals, Homo sapiens is only one of more than

5,000 species."

Creating an Ecological Society: Toward a Revolutionary

Transformation by Fred Magdoff and Chris Williams (2017)

p.158

Christian eschatology (study concerned with the ultimate

destiny of the individual soul and the entire created order)

and the idea of linear time took over from the people’s

strong connection with nature and the ever-changing seasons.

Although, in early medieval times, according to David Ewing

Duncan in The Calendar, the peasants still lived and

died “in a continuous cycle of days and years that to them

had no discernible past or future.”

Different seasonal festivals such as the solstice, the

Nativity, Saturnalia, Yuletide, the Easter hare and Easter

eggs etc. all had pre-Christian connections but old habits

died hard and left the church no choice but to incorporate

some aspects of them into their own traditions over time.

Feminism vs class

While some aspects of the culture of prehistory are still

with us today, interpretation of the artifacts from

archeological digs has always been open to controversy. For

example, Cynthia Eller in her book The Myth of

Matriarchal Prehistory: Why An Invented Past Will Not Give

Women a

Future believes that the theory of a prehistoric

matriarchy (female rulership) was “developed in 19th

century scholarship and was taken up by 1970s second-wave

feminism following Marija Gimbutas.” However, the feminist

historian Max Dashu

notes that Eller “makes no distinction between scholarly

studies in a wide range of fields and expressions of the

burgeoning Goddess movement, including novels, guided tours,

market-driven enterprises. All are conflated all into one

monolithic ‘myth’ devoid of any historical foundation.”

The important point here is that ideas of matriarchal

prehistory have been used in feminist theory to blame men

for war and violence today (ignoring Thatcher and May).

Sure, men have been dominant in the warring elites but many,

many more men were caught up in the enslaved soldiers,

miners and farmers classes. And as it was violence that was

used to enslave them in the first place historically, then

surely it would be no surprise if violence is used by them

in the fight back against their slavery (class struggle).

The reappraisal of our ancient past and our relationship

with nature has become an urgent necessity as climate chaos

occupies more and more of our time and energy. It is not too

late to learn from the myths of the Golden Age and Ovid’s

ancient complaints to create a better future.

This let me further add, that Nature knows

No steadfast station, but, or ebbs, or flows:

Ever in motion; she destroys her old,

And casts new figures in another mould.

— Ovid, Metamorphoses

Book 15

Notes:

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist,

lecturer and writer. His

artwork

consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical

themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of

Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema,

art and politics along with research on a database of

Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can

be viewed country by country at

http://gaelart.blogspot.ie/.

Read other articles by Caoimhghin.

This article was posted on

Friday, April 27th, 2018

Sex, Drugs and Rollickin’ Roles:

Christmas and Our Ever-Changing Relationship with Nature

by Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin / December

20th, 2017

Traditions of the

Winter Solstice

Christmas is an ancient feast that has many positive

associations for people around the world. While the bible places the

birth of Christ in Bethlehem it does not say when, but by the 4th

century the Churches in the East were celebrating it on January 6

and the Churches of the West on December 25.

One thing is certain about Christmas is that it is

rooted in many traditions and superstitions relating to nature that

existed long before Christmas and many have continued in one form or

another to the present day. The many strands of Christmas can be

seen in the variety of different traditions associated with, or

originating in, places all over Europe. These strands are, inter

alia, the solstice, the Nativity, Saturnalia, Yuletide, St

Nicholas, Father Christmas, and Grandfather Frost (Ded Moroz).

The association of Christmas with its earlier

midwinter nature worship traditions declined as the Church exerted

its power and authority over pagan practices and in more recent

centuries as the industrial revolution took people away from the

land and into the cities and factories. Since then industrialisation

has taken over many aspects of people’s lives as they shifted from

being producers to consumers.

As direct contact with nature declined and

scientific knowledge was applied to production, our lives were made

easier by an abundance of relatively cheap goods and food. These

benefits have come at another price though as industrialisation and

technology the world over pushes nature further and further into

ecological crises. There is much discussion and debate about the

potential for a tipping point as the destruction of ecosystems and

climate change move headlong towards irreversible damage of the

Earth’s biosphere.

This has come about, partly due to our alienation

from nature, but also due to a system which blinds us to the

excesses of production through mass media, and Christmas has become

the vehicle for the worst excesses of industrialisation,

commercialisation and commodification. However, this is a gross

distortion of its roots in respecting nature and nature worship

which was ultimately about a heightened awareness of survival in an

unpredictable world.

Sex

The predominant figure of Christmas has become Santa

Claus (Dutch: Sinter Klaas) and originated in the stories around St

Nicholas, the 4th century Bishop of Myra (Turkey), giving anonymous

gifts to help people in need or trouble.

In many European regions St Nicholas came door to door with a

bishop’s mitre and crosier on his feast day, December 6. He was

accompanied by his helper Ruprecht or Krampus as he is known in the

Alpine regions. Krampus is depicted as half goat and half demon and

punished misbehaving children with a rod.

Krampus

It is believed that Krampus derives from the much

earlier pre-Christian Norse mythology and that he was the son of the

god of the underworld Hel. While the name Krampus is believed to

originate from Krampen meaning ‘claw’, Ruprecht is believed to be

from “Hruodperaht” meaning “gloriously shining one” another name of

Wotan. Their negative status is likely the result of Christian

attempts to assert dominance over the pagan peoples of the time, in

the same way that the Celtic goddess Bridget was demoted by the

Christian church to St Bridget. Krampus is an evil fertility demon

who scares children (reversing his earlier role as fertility god)

with his hazel wood rod:

The hazelnut was holy to Donar, the God of

marital and animal fertility. The hazel wood rod was considered

a great rod of life. With this symbol of the penis, women and

animals were beaten “with gusto” in order for them to become

fertile.

This fertility rite has continued to the present day

on Easter Mondays in the Czech Republic when young women are whipped

with a braided rod of willow called a

pomlázka to “assure womankind with good health, fresh look and

keep fertility. The girls then give coloured or painted eggs to boys

and men as a sign of their thanks and forgiveness.”

Pomlázka

During the 12th century the church

tried to end the Krampus celebrations but it seems that, like with

many popular traditions, they re-surfaced and were re-integrated

back into church traditions. Unlike the ‘demonised’ Krampus, the

Christian St Nicholas distributed typical gifts of nuts, dried

fruits, chocolate, spices and toys.

These gifts were also symbols of fertility. Hazelnuts helped people

survive winter as they could be easily stored and were rich in fats

and vitamins. Apples were associated with the Tree of Paradise and

dried fruits such as oranges and lemons served as fertility symbols

in the Mediterranean countries as they were the first fruit of the

year and thus herald a good harvest.

Drugs

Another major association of Norse mythology with

Christmas is the reindeer pulling the Santa’s sleigh. The first

mention of St Nicholas in the air in popular mythology is of him

“riding jollily among the tree-tops, or over the roofs of the

houses, now and then drawing forth magnificent presents from his

breeches pockets and dropping them down the chimneys of his

favourites” is by Washington Irving in his satirical work, A

History of New-York from the Beginning of the World to the End of

the Dutch Dynasty, by Diedrich Knickerbocker (1809). At

this point St Nicholas was not associated with Christmas and

presents were exchanged on the night before his feast day on

December 6.

However, in a poem written in 1822, Clement Moore

has St Nicholas arrive with his presents on the night before

Christmas and in “a miniature sleigh, and eight tiny reindeer” who

“would mount to the sky […] with a sleigh full of toys” and then go

down the chimneys to deliver his gifts thus shifting celebrations of

St Nicholas in the United States from his feast day on December 6 to

Christmas Eve on

December 24 instead.

The phenomenon of flying animals has long been

associated in Norse mythology with Wotan (Odin) and his flying eight

legged horse Sleipnir, and with Thor and his flying goat-drawn

chariot.

”Odin and Sleipnir” (1911) by

John Bauer

Wotan is depicted as one-eyed and long-bearded in

Old Norse texts and is a fierce god associated with wisdom, healing

and war. Children would leave straw in their boots for Sleipnir by

the hearth and Wotan would exchange it for a gift in return for

their

kindness.

Thor was also depicted as a fierce god of thunder

and lightning, storms, oak trees and fertility. Another god, Morozko,

the powerful and cruel Slavic god of frost and ice could freeze

people and landscapes at will, became known as

Ded Moroz (Grandfather Frost) but was eventually demonised by

the Russian Orthodox Church. As our fear of nature declined and

Christmas became more of a child-centered celebration, the

depictions of these gods became less fierce over time.

‘

Thor and Tyr

in their Goat-Drawn Chariot (From “The Book of Myths” by Amy Cruse,

1925)

The flying aspect of Santa’s reindeers is believed

to refer to the reindeers’ fondness for Fly Agaric mushrooms

associated with Old Nordic Shamanism. The Shamanic ‘flight of the

soul’ was part of the culture of people in arctic Europe and Siberia

who would communicate with the souls of their ancestors in an

altered state of consciousness helped along by the hallucinogenic

mushrooms.

Like the Church attempts to eradicate the earlier fertility

traditions and the gods associated with them, shamanism has been

considered mere superstition and attacked by both Churches and

governments alike.

It seems that what shamanism and fertility rites

have in common is the idea of directly engaging with nature to

secure desired material or spiritual goals. Both Krampus and

Shamanism have been associated with

Satan who “uses deception and demonic spirits seeking our

destruction” yet their popularity has ebbed and flowed over the

centuries without disappearing altogether.

Rollickin’ Roles

Similarly the Bacchanalian aspect of Christmas celebrations is a

survival of Saturnalia, the Roman celebration of

Saturn the “god of generation, dissolution, plenty, wealth,

agriculture, periodic renewal and liberation” which could also be

described as an engagement with the cycles of nature.

Saturnalia was “a time of feasting, role reversals, free speech,

gift-giving and revelry” held on

December 17 of the Julian calendar

and was subsequently extended to 23 December. Saturnalia originated

as a farmer’s festival to mark the end of the autumn planting season

in honour of Saturn (satus means sowing).

According to Justinus, the 2nd century Roman historian, these

celebratory aspects of Saturnalia derived from, and were explained

by, its origins with pre-Roman peoples of Italy

who:

were the Aborigines, whose king, Saturnus, is said to have been

a man of such extraordinary justice, that no one was a slave in

his reign, or had any private property, but all things were

common to all, and undivided, as one estate for the use of every

one; in memory of which way of life, it has been ordered that at

the Saturnalia slaves should everywhere sit down with their

masters at the entertainments, the rank of all being made equal.

Once again the association with nature and the Golden Age (when

people lived in peace and harmony) forms the basis of a celebration

which was to be co-opted by the Church and eventually attacked for

its excesses. According to a

Puritan minister in 17th century England, Increase Mather,

Christmas occurred on December 25 not because “Christ was born in

that month, but because the heathens’ Saturnalia was at that time

kept in Rome, and they were willing to have those pagan holidays

metamorphosed into Christian [ones]. Stephen Nissenbaum, in his book

The Battle for Christmas,

writes:

Puritans believed Christmas was basically just a pagan custom

that the Catholics took over without any biblical basis for it.

The holiday had everything to do with the time of year, the

solstice and Saturnalia and nothing to do with Christianity.

Presumably the masters could not cope with the concept of equality

and saw Saturnalia instead as a role reversal. In pre-industrial

England people would elect a Lord of Misrule who would be in charge

of Christmas festivities and who even had license to poke fun at the

nobility.

Yet the Lords of Misrule were an important aspect of Christmas as

the reversal of traditional social norms was a safety valve for

class tensions in England. It was around this time that the

personification of Christmas as Father Christmas began to appear.

Father

Christmas 1848

He was associated not with children, presents,

chimneys or stockings, but with adult merrymaking and feasting.

During Christmas ‘great quantities of brawn, roast beef,

‘plum-pottage’, minced pies and special Christmas ale were consumed’

and people enjoyed singing, dancing and card games resulting in

‘drunkenness, promiscuity and other forms of excess.’ Thus when the

Puritans took over government in the 1640s they tried ‘to

abolish the Christian festival of Christmas and to outlaw the

customs associated with it’. The satirical Royalist poet, John

Taylor, wrote in The Complaint of Christmas:

All the liberty and harmless sports, with the merry gambols,

dances and friscals [by] which the toiling plowswain and

labourer were wont to be recreated and their spirits and hopes

revived for a whole twelve month are now extinct and put out of

use in such a fashion as if they never had been. Thus are the

merry lords of misrule suppressed by the mad lords of bad rule

at Westminster.

However by the 1650s it was reported that the taverns were full on

Christmas day, churches were decorated in rosemary as usual,

Christmas Boxes had been given out, presents exchanged and mummers

paid despite the bans. Worse still violence broke out in London

when:

a large crowd of Londoners gathered to prevent the mayor and his

marshalls removing the Christmas decorations which some of the

city porters had draped around the conduit in Cornhill. The

confrontation ended in uproar, with arrests, injuries, and the

bolting of the mayor’s frightened horse.

The Christmas celebrations returned with Charles II in 1660 and

showed once again the attempt to impose a narrow religious view on

the multifaceted ancient traditions of people had failed.

Trees

Somewhat earlier, in the 14th and 15th centuries in Germany,

craftsmen began to decorate their guild halls with trees and

adorning them with fruits and nuts. This eventually led to the

German, Charlotte, who married King George III in 1761, potting up

and decorating a yew tree and initiating the custom in England.

Legend has it that in Germany, St Boniface, an historical figure

from the 7th century, saw a group of people honouring the sacred

tree, Donar’s Oak (sometimes referred to as Thor’s Oak) somewhere

around Hesse, became angry and chopped the tree down (and added

insult to injury by using the wood to build his church).

St Boniface chopping the oak tree

Sacred trees and sacred groves were very important to the Germanic

peoples and were too important to be cut down. Again we can see that

the earlier traditions of pre-Christian society revolved around

revering

nature:

Some were wont secretly, some openly to sacrifice to trees and

springs; some in secret, others openly practiced inspections of

victims and divinations, legerdemain and incantations; some

turned their attention to auguries and auspices and various

sacrificial rites; while others, with sounder minds, abandoned

all the profanations of heathenism, and committed none of these

things.

Over time, cutting the evergreen tree and bringing it indoors became

an important part of Christmas traditions [see my previous article

on

Christmas trees] despite church proscription, because of its

shamanic-pagan past.

Another early nature-based tradition is the wassail

in England.

Wassailing is a very ancient custom that is referenced in

history as early as the eighth-century poem Beowulf. The word

‘wassail’ is believed to be derived from the Old Norse ‘ves heil’

and the Old English ‘was hál’ and meaning “be in good health” or “be

fortunate.” The wassail had an important significance for

farmers:

In parts of Medieval Britain, a different sort of wassailing

emerged: farmers wassailed their crops and animals to encourage

fertility. An observer recorded, “They go into the Ox-house to

the oxen with the Wassell-bowle and drink to their health.” The

practice continued into the eighteenth century, when farmers in

the west of Britain toasted the good health of apple trees to

promote an abundant crop the next year. Some placed cider-soaked

bread in the branches to ward off evil spirits. In other

locales, villagers splashed the trees with cider while firing

guns or beating pots and pans.

Wassailing the Apple Tree

The

Apple Tree Wassail lyrics anticipate the next year and a good

crop:

(It’s) Our wassail jolly wassail!

Joy come to our jolly wassail!

How well they may bloom, how well they may bear

So we may have apples and cider next year.

Solstice and the Unconquered Sun

Our awareness of mid winter and the solstice (‘sun

stands still’) is shown to go back to the late Neolithic and Bronze

Age with Newgrange in Ireland and Stonehenge in England. In both

cases the monuments have been aligned to the solstice, sunrise at

Newgrange and sunset at Stonehenge. It has been the occasion of

celebrations, rituals and gatherings as the sun appears to be reborn

and the days start getting longer again. After this time food became

scarce (January to April) which were known as the ‘famine months’.

It was the last feast of the year as cattle were slaughtered and

wine and beer were ready for drinking. The ‘rebirth’ of the sun was

known as Sol Invictus or the ‘unconquered sun’ god during the Roman

Empire in the 3rd century CE and the Emperor Aurelian dedicated a

temple to Sol to be celebrated on

December 25. Solar deities have been

represented as both gods and goddesses in different cultures and are

particularly important in mid winter when the sun is low in the sky.

In many countries in Europe the tradition of the Yule log burning

was an important festival to help strengthen the weakened sun.

Yule log

A

large log, big enough to burn for the 12 days of Christmas, was

brought into the houses and burned. It was believed to have

originated with the Norse and the Celts who had large bonfires to

welcome the return of the sun. The log was thought to have magical

properties and the ashes were then used as fertiliser and as cures

for both people and animals and would protect them for the year to

come.

Nature

Throughout the world there have been many forms of

nature worship demonstrating that people respected and feared nature

in equal amounts over the millennia. We have a complex relationship

with nature, indeed we are an important part of nature. We have to

negotiate every aspect of that relationship, be it food, water,

reproduction, climate (storms avalanches, floods, droughts, fires),

the seasons, the geophysical (earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanoes),

light (length of day, sleeping during hours of darkness) etc.

In the past people hoped and prayed that in the next

year nature would allow them to live well again and consequently

treated nature with respect. To do that people were careful not to

over-exploit nature in various ways: by leaving land fallow, having

food taboos, allowing areas to regenerate by moving on, by not

over-using a food resource, thus creating the basis of

sustainability into the future. Their respectful attitude to nature

was reflected in what we call superstitions and paganism but it

allowed them to celebrate Christmas without guilt in the knowledge

that they had treated nature well and that nature would reciprocate

with a bountiful harvest the next year.

Today, on the other hand, we are alienated from this

way of thinking and living to the extent that people have lost

direct control of their relationship with nature. The ever

increasing industrial overproduction of meat, over-fishing,

over-fertilisation, deforestation, air pollution and extractivism is

pushing nature to extremes and already we are seeing the

catastrophic results of this in climate change. Maybe as climate

change brings ever fiercer storms and destruction of food production

we will learn to respect and fear nature again.

https://dissidentvoice.org/2017/12/sex-drugs-and-rollickin-roles-christmas-and-our-ever-changing-relationship-with-nature/

Notes:

|