|

Home

Irish culture and history

Nissan Huts (Demolition of H Blocks)

Oil on canvas

60cm x 60cm / 23.6 in x 23.6 in

Notes

"Long Kesh / Maze

prison was infamous as the major holding centre for paramilitary

prisoners during the course of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Some of

the major events of the recent conflict centred on, emanated from, and

were transformed by it, including the burning of the internment camp in

1974, the protests and hunger strikes of 1980-1981, the mass escape of

PIRA prisoners in 1983, and the role of prisoners in facilitating and

sustaining the peace process of the 1990s. Now, over a decade

after the signing of the Belfast Agreement (1998), Long Kesh / Maze

remains one of the most contentious remnants of the conflict and has

become central to debates about what we do with such sites, what they

mean, and how they relate to contemporary rememberings of the difficult

recent past."

An

Archaeology of the Troubles: The dark heritage of Long Kesh/Maze prison

Laura McAtackney (2014)

See:

http://ukcatalogue.oup.com/product/9780199673919.do

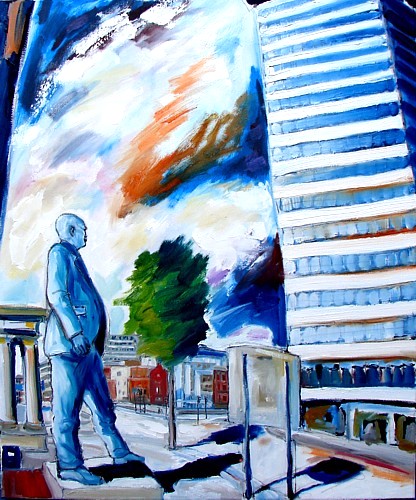

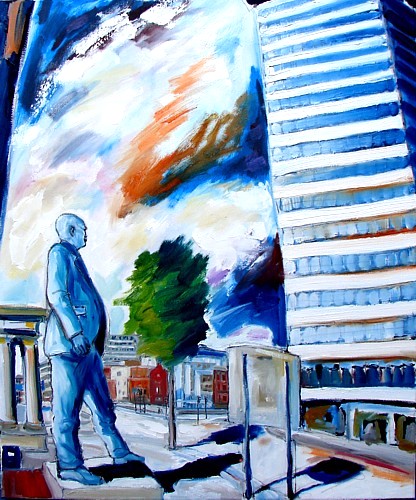

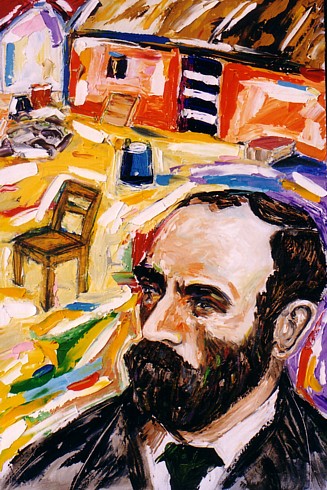

The Rise and Fall of James Connolly,

Beresford Place, Dublin.

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 60cm / 19.7 in x 23.6 in

Sold

Notes

'In “The Rise and Fall of James Connolly”, the statue of Larkin’s

partner during the Dublin lock-out of 1913 stands outside Liberty Hall.

Today the building shelters the offices of the Services, Industrial and

Technical Union (SIPTU trade union) and until it was superseded by the

Elysian building in Cork in September 2008, the Liberty Hall building in

Dublin was the tallest storeyed building in Ireland. [...] In the years

leading up to the 1916 insurrection it harboured the Irish Transport and

General Workers Union when it was created in the early years of the 20th

century and the Irish Citizen Army (ICA). As in the other paintings, the

past is juxtaposed onto buildings of present-day Dublin creating a

city-space in which different moments of history collide. [...] The

plinth of Connolly’s statue is invisible and the statue almost seems

alive. Connolly himself seems suddenly overwhelmed and his arrogant

posture melts into a shadow onto the pavement, as the orange shape in

the sky, reminiscent of the fall of Icarus, hints at Connolly's failure

to fulfill his dreams.'

See: 'Post Celtic Tiger landscapes in Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin's

paintings' by Marie Mianowski in

Post Celtic Tiger Ireland: Exploring New Cultural Spaces

Edited by Estelle Epinoux and Frank Healy (2016)

http://www.cambridgescholars.com/post-celtic-tiger-ireland

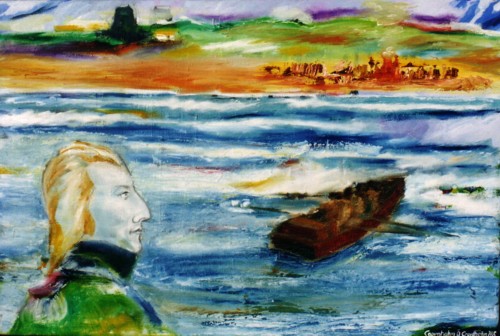

Bob Doyle (1916-2009) Commemoration

(The last Irish Brigadista)

O'Connell Street, Dublin

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 60cm / 19.7 in x 23.6 in

Notes

"Robert Andrew "Bob" Doyle (12 February 1916 – 22 January 2009) was a

communist activist and soldier from Ireland. He was active in two armed

conflicts; the Spanish Civil War as a member of the International

Brigades and the Second World War as a member of the British Empire's

Merchant Navy. [...] He initially attempted to travel to Spain by

stowing away aboard a boat bound for Valencia, where he was detained and

expelled. He eventually returned by crossing the Pyrenees from France.

After he returned to Spain, he reported to a battalion at Figueras. He

was initially required to train new recruits because of his IRA

experience, but disobeyed orders to get to the front. After fighting at

Belchite, he was captured at Gandesa by the Italian fascist Corpo Truppe

Volontarie in 1938, along with Irish International Brigade leader Frank

Ryan. He was imprisoned for 11 months in a concentration camp near

Burgos. There he was once brought out to be shot and he was regularly

tortured by Spanish fascist guards and interrogated by the Gestapo

before being released in a prisoner exchange."

See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bob_Doyle_(activist)

Great Famine Memorial,

Custom House Quay, Dublin.

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 60cm / 19.7

in x 23.6 in

Sold

Notes

"Among them, Great Famine Memorial, Custom House Quay, Dublin (2007, 50

x 60 cm) depicts with accuracy the Bronze statues commemorating the

Great Irish Famine, mainly caused by potato blight, between 1845 and

1851. These sculptures were made by Rowan Gillespie and were placed in

1997 on The Customs House Quay, on the bank of the Liffey River, because

they were inspired by the following text: “A procession fraught with

most striking and most melancholy interest, wending its painful and

mournful way along the whole line of the river to where the beautiful

pile of the Custom House is distinguishable in the far distance”, a

quotation from The Irish Quarterly Review, dated 1854. [...] Another

allusion to Ireland’s riches corresponds to the function of the

buildings in the background of Great Famine Memorial. Indeed, the

largest can easily be recognised as the International Financial Services

Centre (IFSC), which is part and parcel of Dublin’s business district,

implemented by The Finance Act (1987) in order to attract foreign

companies with low taxation rates. This area, devoted to offices,

shopping facilities, restaurants and housing for businessmen and women

is highly criticised today, some accusing the government of allowing

companies to enjoy tax reductions whereas the rest of the country

suffers from austerity measures."

'Post Celtic Tiger Expressionism: Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin’s Great

Famine Memorial, Custom House Quay, Dublin (2007)' by Amélie Dochy in

Post Celtic Tiger Ireland: Exploring New Cultural Spaces

Edited by Estelle Epinoux and Frank Healy (2016)

http://www.cambridgescholars.com/post-celtic-tiger-ireland

The colors in this painting have a high contrast between the whites of

the ground, bridge and sky and the shadows or dark windows as well as

the bright yellow-orange of the acid washed copper with that of the blue

in the building and the street. The vibrant contrast shows the true

dichotomy between the world these statues represent and the world they

live in today. The shape of the statues also draws the eyes of the

viewer up the painting almost as if they are arrows pointing to the

International Financial Services Centre (IFSC) in the background. This

piece shows an interesting perspective, instead of including the water

and the sky he instead chose to include the street and this building in

the background. Instead of painting what one might assume an artist

would paint, Ó Croidheáin is making an intentional statement by linking

these two Irish landmarks.

The IFSC is a representation of the low corporate tax rate that benefits

foreign companies establishing business here in Ireland while increasing

taxes for the Irish people. The sentiment behind connecting the starving

Irish ancestors with the IFSC reiterates that had it not been for the

priorities of an indifferent government the starving Irish of the 1800’s

could have died differently. The statues faces are not prominent in this

painting either. It is as if the faceless figures of the famine

represent the Irish people as a whole. Ó Croidheáin has taken the image

of Gillespie’s statues and used it to tell a different story. The idea

that history repeats itself is not a novel concept but one could

interpret that this painting is almost a word of warning,

reminding the viewer what a government indifferent to its citizens is

able to do. Instead seeing Ó Croidheáin’s work as a painting of

Gillespie’s statues, think of it instead as a painting inspired by the

statues, telling a different story with the same resources.

Casey Deal, 'The Great Hunger for Art', (7 Dec 2018)

Larkin's Despair,

O'Connell St, Dublin

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 80cm / 23.6 in x 31.5 in

Sold

Notes

"The three colours of the Irish flag are repeated in most paintings as a

sort of background colour scheme, especially in ‘Larkin’s Despair’ where

the colours of the statue, the plinth and the inscription mirror those

of the Irish flag, although not in equal proportions. In ‘Larkin’s

Despair’ however, the irony appears through the exaggerations of the

painter: a huge white Limo stretches its arrogance along three blocks of

buildings as if to emphasize the grotesque exuberance of Celtic Tiger

wealth. Also the packed crowd of the 1923 photograph [of Larkin

speaking, upon which the sculpture is based], although less enthusiastic

than the 1913 one is reduced to nothing in the late Celtic Tiger period.

The streets are almost deserted with only a few people crossing

O’Connell street on both sides of Larkin’s statue but ignoring it.

Larkin is left all alone, with his arms stretched in despair and his

head down as if he were quietly sobbing."

See: 'Post Celtic Tiger landscapes in Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin's

paintings' by Marie Mianowski in

Post Celtic Tiger Ireland: Exploring New Cultural Spaces

Edited by Estelle Epinoux and Frank Healy (2016)

http://www.cambridgescholars.com/post-celtic-tiger-ireland

The left hand side of the painting depicts the GPO [General Post

Office].

"During the Easter Rising of 1916, the GPO served as the headquarters of

the uprising's leaders. The building was destroyed by fire in the course

of the rebellion and not repaired until the Irish Free State government

took up the task some years later."

See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/General_Post_Office,_Dublin

"The famous photograph of James Larkin that inspired the monument [by

Dublin sculptor Oisín Kelly (1915–81)], was taken by Joe Cashman in

April 1923."

See:

http://www.historyireland.com/20th-century-contemporary-history/an-inspiration-to-all-who-gaze-upon-it/

The right hand side of the painting depicts a stretch limo, popular form

of celebratory transport used by working class people during the Celtic

Tiger years.

Larkin's Delight,

O'Connell St, Dublin

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 80cm / 23.6 in x 31.5 in

Sold

Notes

"By contrast in ‘Larkin’s

Delight’, the crowd is there, demonstrating and taking its destiny in

hands, claiming its own rights out on the street with Larkin’s statue

thrilled with delight."

See: 'Post Celtic Tiger

landscapes in Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin's paintings' by Marie Mianowski in

Post Celtic Tiger Ireland: Exploring New Cultural Spaces

Edited by Estelle Epinoux and Frank Healy (2016)

http://www.cambridgescholars.com/post-celtic-tiger-ireland

Parnell's Providence,

O'Connell St, Dublin

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 80cm / 23.6 in x 31.5 in

Notes

"Caoimhghin Ó

Croidheáin’s “Parnell” painting ironically shows Parnell’s statue

pointing at a passing bus on O’Connell street. On the painting,

Parnell’s stretched out hand points at a passing bus decorated with a

huge ad that reads: ‘wealth warning’. More explicitly than on the

others, the irony is blatantly visible on that painting where ‘wealth

warning’ replaces ‘health warning’ as if the statue had in turn become a

viewer of our contemporary world, revealing how, through landscapes, the

past continues to work in the present."

See: 'Post Celtic Tiger

landscapes in Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin's paintings' by Marie Mianowski in

Post Celtic Tiger Ireland: Exploring New Cultural Spaces

Edited by Estelle Epinoux and Frank Healy (2016)

http://www.cambridgescholars.com/post-celtic-tiger-ireland

'Wealth Warning' was the tag line used in an advertising campaign by the

travel agency Budget Travel in the middle 2000s.

The statues of historical figures such as Jim

Larkin, Daniel O’Connell, Charles Stewart Parnell, and James Connolly

look down on a new city that sits uncomfortably with their varieties of

nationalism and socialism.

These

symbols of the past, standing in silent judgment of the follies of the

present, act as control rods in the current economic fission reminding

its old and new, wealthy and poor citizens alike of past struggles and

hardships.

'Young Ireland' vs Old Ireland,

College Green, Dublin

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 80cm / 23.6 in x 31.5 in

Sold

Notes

"In

the painting “Young Ireland vs Old Ireland”, the sculpture of Thomas

Davis’ silhouette is represented from a very low angle so that the

statue seems to be overlooking both the crowd and College Green. The

title of the painting echoes the “Young Ireland” movement to which

Davis’ belonged in the 1840s, a phrase coined in the first place as a

dismissive term by Daniel O’Connell to describe his inexperienced allies

in the Repeal Movement. Thomas Davis subsequently became the chief

leader of the Young Ireland movement and in the 1870s, the term came to

refer to the nationalists inspired by him.

The statue overlooks College Green as a tribute to Trinity College where

he was educated and to the University education he wished to promote for

Irish students of all backgrounds and confessions. [...]

In ‘Young Ireland vs Old Ireland’ the ironical contrast also stems from

a discrepancy between the past and the present. Davis’ statue outside

College Green is surrounded by a cheering crowd gathered there to watch

a Macnas parade. ‘Macnas are master storytellers who inspire and engage

audiences by creating big, bold, visual shows and performances through

world-class theatrical spectacle ’. On the painting a colourful drummer

advances, playing on exotic looking drums to an anonymous crowd of

hooded youths, and Davis’ famous ballad ‘A Nation once again ’ resonates

in the ears of the viewer of Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin’s painting. As

Christie Fox points out, Macnas reinterprets folk tales through

contemporary issues, the priority being entertainment over education, a

choice that might have startled Davis whose preoccupation with education

was paramount."

See: 'Post Celtic Tiger

landscapes in Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin's paintings' by Marie Mianowski in

Post Celtic Tiger Ireland: Exploring New Cultural Spaces

Edited by Estelle Epinoux and Frank Healy (2016)

http://www.cambridgescholars.com/post-celtic-tiger-ireland

Macnas (Irish for "Joyful Abandonment") incorporated Primitivism /

Tribalism in its artistic style, hence the reference to 'Old Ireland'.

O'Connell's Delight,

O'Connell St, Dublin

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

80cm x 120cm / 31.5 in x 47.2 in

Sold

Notes

O'Connell's Delight refers to the wealth of the middle classes

symbolised by the profusion of SUVs [Sports Utility Vehicle] in Dublin.

O'Connell fought for the rights of the middle classes but was less

sympathetic to the rights of the working class:

"O 'Connell,

long revered in Irish history as 'The Liberator' was a consistent

enemy of the working class and laid the foundations for the anti

English and anti socialist premises at the root of much of Irish

nationalism. O Connell's family background is of interest as are

some of his less publicised political activities. O Connell was born

into a family of the minor landowning catholic gentry. He received

his education in France during the period of the French Revolution,

which swept away the reactionary catholic ancient regime forever.

These experiences are held as the formative influences on a

political career in which he famously declared the Irish freedom was

not worth the shedding of a drop of blood. It is a less well known

fact that O Connell was a volunteer with the Lawyers Yeomanry Corps

which rounded up supporters of Robert Emmet's failed rebellion in

1803, was the suppression of Irish freedom worth paying such a

price?"

"Against the Red Flag" Socialism and Irish Nationalism 1830 - 1913

Mags Glennon [See:

http://struggle.ws/cc1913/flag.html]

"O'Connell 'cherished a romantic attachment for his "darling little

Queen" (Victoria)' [p100] and when he took his seat as a supporter

of the Whig Government in the House of Commons 'voted against a

proposal to shorten the hours of child labour in factories' in 1838

[p104/5]."

[See P. Berresford, Ellis, A History of the Irish Working Class.

London, Victor Gollancz Ltd., 1972].

“There was no

tyranny equal to that which was exercised by the trade-unionists in

Dublin over their fellow labourers [O'Connell]."

in James Connolly Labour In Irish History

[See:

https://www.marxists.org/archive/connolly/1910/lih/chap12.htm]

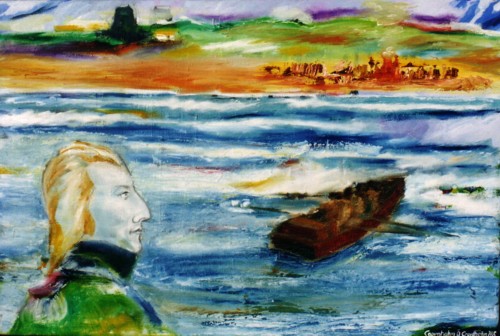

Eoghan Rua O Neill (c1590-1649)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 60cm

Notes

Owen Roe O'Neill (Irish: Eoghan Ruadh Ó Néill; c. 1585 – 6 November,

1649) was a seventeenth-century soldier and one of the most famous of

the O'Neill dynasty of Ulster in Ireland. O'Neill left Ireland at a

young age and spent most of his life as a mercenary in the Spanish Army

serving against the Dutch in Flanders during the Eighty Years' War.

Following the Irish Rebellion of 1641, O'Neill returned and took command

of the Ulster Army of the Irish Confederates. He enjoyed mixed fortunes

over the following years but won a decisive victory at the Battle of

Benburb in 1646. Large-scale campaigns to capture Dublin and Sligo were

both failures.

[See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Owen_Roe_O%27Neill]

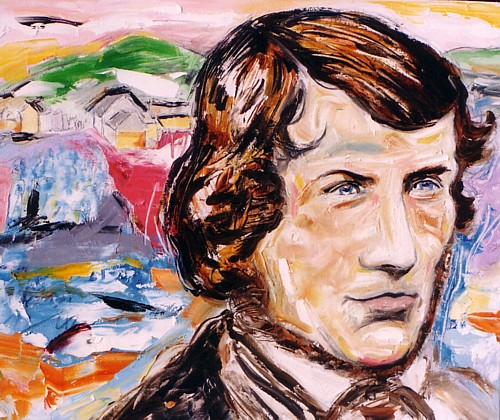

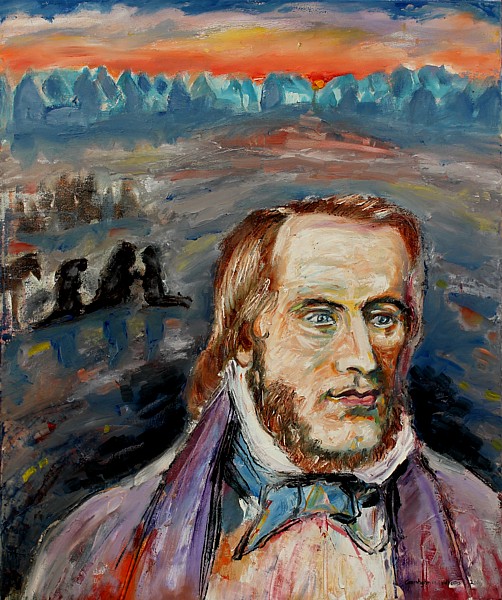

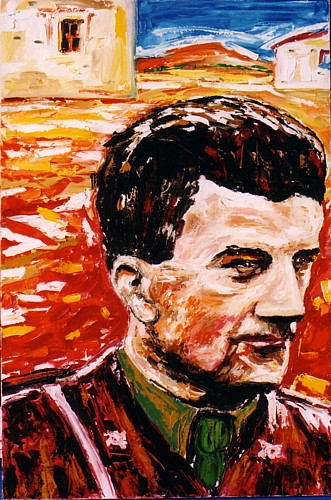

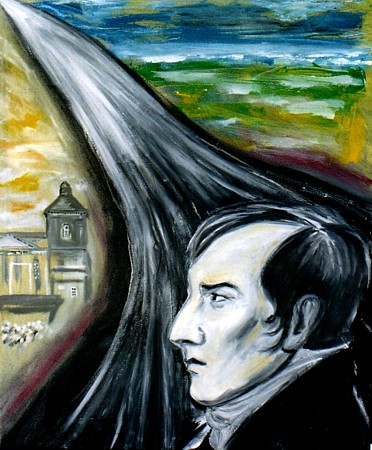

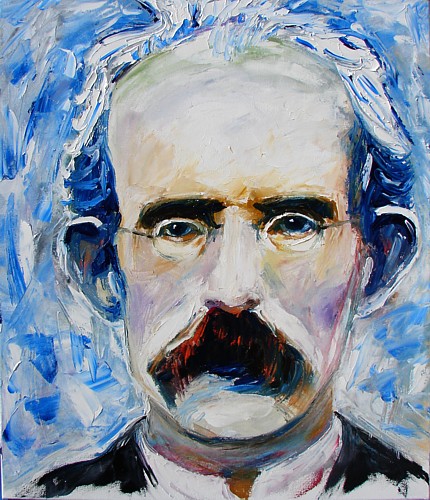

Wolfe Tone (1763-1798)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 80cm

Notes

Theobald Wolfe Tone, posthumously known as Wolfe Tone (20 June 1763

– 19 November 1798), was a leading Irish revolutionary figure and one of

the founding members of the United Irishmen, and is regarded as the

father of Irish republicanism and leader of the 1798 Irish Rebellion. He

was captured at Letterkenny port on 3 November 1798.

See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolfe_Tone]

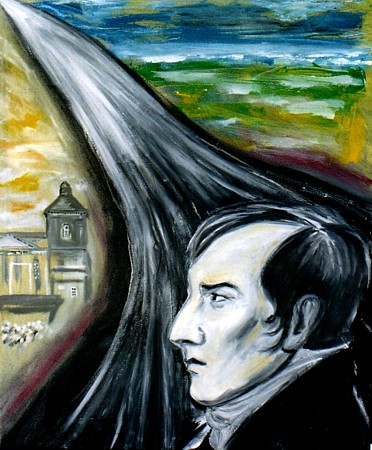

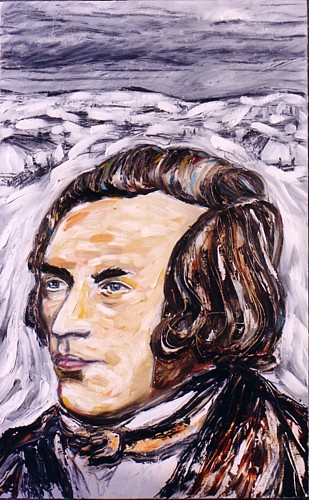

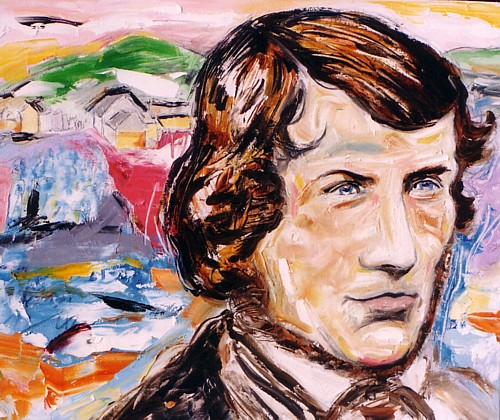

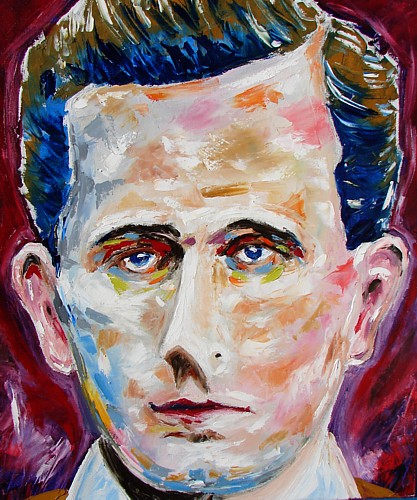

Robert Emmet (1780-1803)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 60cm

Notes

Robert Emmet (4 March 1778 – 20 September 1803) was an Irish

nationalist and Republican, orator and rebel leader. After leading an

abortive rebellion against British rule in 1803 he was captured then

tried and executed for high treason against the British king. He came

from a wealthy Anglo-Irish Protestant family who sympathised with Irish

Catholics and their lack of fair representation in Parliament. The Emmet

family also sympathised with the rebel colonists in the American

Revolution. While Emmet's efforts to rebel against British rule failed,

his actions and speech after his conviction inspired his compatriots.

[See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Emmet]

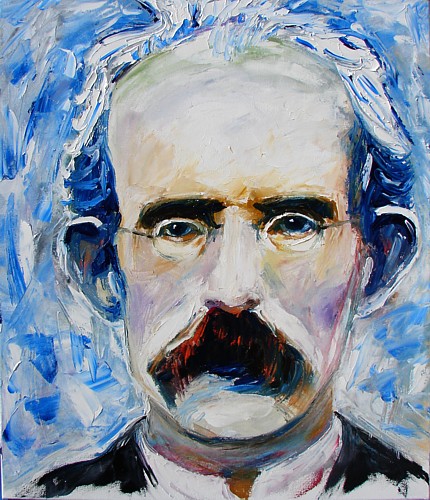

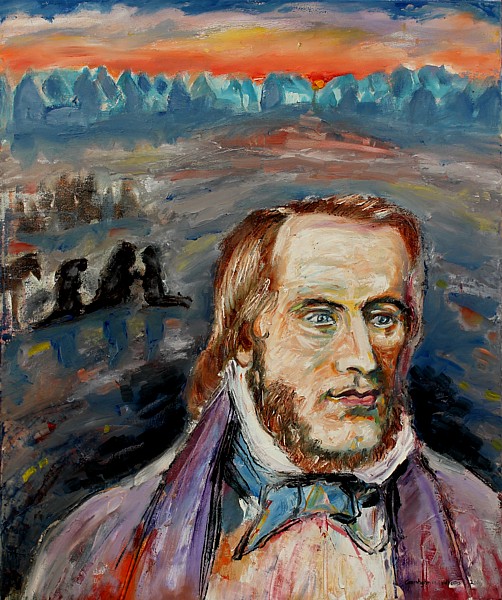

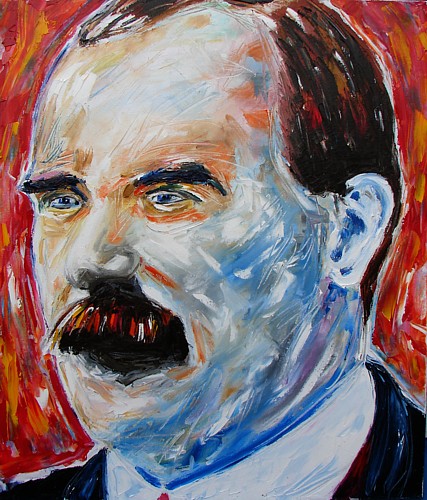

John Mitchel (1815-1875)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 60cm

Notes

John Mitchel (Irish: Seán Mistéal; 3 November 1815 – 20 March 1875)

was an Irish nationalist activist, author, and political journalist.

Born in Camnish, near Dungiven, County Londonderry and reared in Newry,

he became a leading member of both Young Ireland and the Irish

Confederation. After moving to the United States in the 1850s, he became

a pro-slavery editorial voice. Mitchel supported the Confederate States

of America during the American Civil War, and two of his sons died

fighting for the Confederate cause. He was elected to the House of

Commons of the United Kingdom in 1875, but was disqualified because he

was a convicted felon. His Jail Journal is one of Irish nationalism's

most famous texts.

[See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Mitchel]

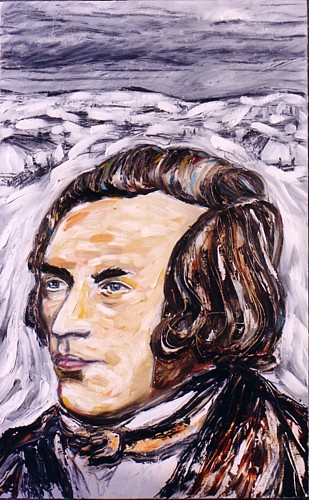

Thomas Davis (1814-1845)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 60cm

Notes

Thomas Osborne Davis (14 October 1814 – 16 September 1845) was an

Irish writer who was the chief organiser of the Young Ireland movement.

[...] Davis gave a voice to the 19th-century foundational culture of

modern Irish nationalism. Formerly it was based on the republicans of

the 1790s and on the Catholic emancipation movement of Daniel O'Connell

in the 1820s-30s, which had little in common with each other except for

independence from Britain; Davis aimed to create a common and more

inclusive base for the future. He established The Nation newspaper with

Charles Gavan Duffy and John Blake Dillon. He wrote some stirring

nationalistic ballads, originally contributed to The Nation and

afterwards republished as Spirit of the Nation, as well as a memoir of

Curran, the Irish lawyer and orator, prefixed to an edition of his

speeches, and a history of King James II's parliament of 1689; and he

had formed many literary plans which were unfinished by his early death.

He was a Protestant, but preached unity between Catholics and

Protestants. To Davis, it was not blood that made a person Irish, but

the willingness to be part of the Irish nation.

[See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Davis_(Young_Irelander)]

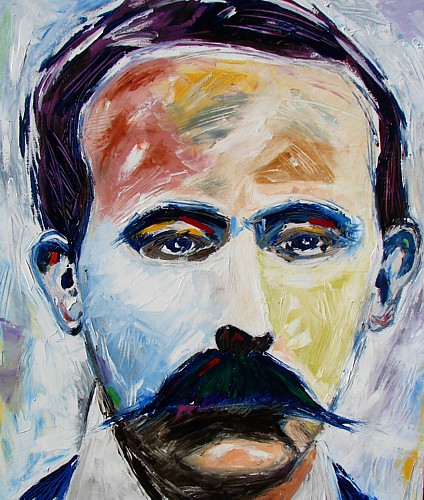

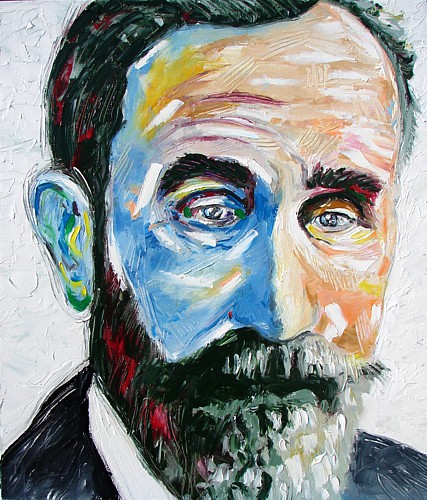

Charles Gavin Duffy (1816-1903)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 80cm

Notes

The Rt. Hon. Sir Charles Gavan Duffy, KCMG, PC (12 April 1816 – 9

February 1903), Irish nationalist, journalist, poet and Australian

politician, was the 8th Premier of Victoria and one of the most

colourful figures in Victorian political history. Gavan Duffy was one of

the founders of The Nation and became its first editor; the two others

were Thomas Osborne Davis, and John Blake Dillon, who would later become

Young Irelanders. All three were members of Daniel O'Connell's Repeal

Association. This paper, under Gavan Duffy, transformed from a literary

voice into a "rebellious organisation". As a result of The Nation's

support for Repeal, Gavan Duffy, as owner, was arrested and convicted of

seditious conspiracy in relation to the Monster Meeting planned for

Clontarf, just outside Dublin, but was released after an appeal to the

House of Lords. In August 1850, Gavan Duffy formed the Tenant Right

League to bring about reforms in the Irish land system and protect

tenants' rights, and in 1852 he was elected to the House of Commons for

New Ross.

[See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_Gavan_Duffy]

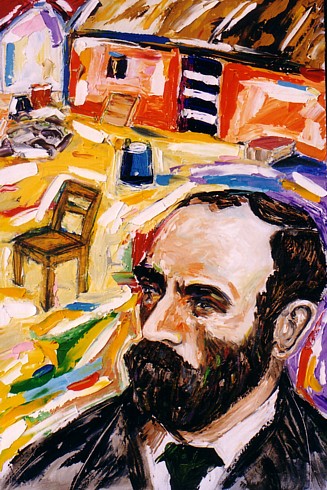

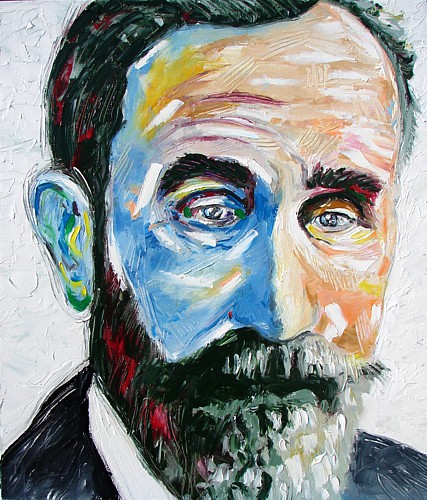

Michael Davitt (1846-1906)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 90cm

Sold

Notes

Michael Davitt (Irish: Mícheál Mac Dáibhéid; 25 March 1846 – 30 May

1906) was an Irish republican and agrarian campaigner who founded the

Irish National Land League. He was also a labour leader, Home Rule

politician and Member of Parliament (MP). [...] On 16 August 1879, the

Land League of Mayo was formally founded in Castlebar, with the active

support of Charles Stewart Parnell. On 21 October it was superseded by

the Irish National Land League. Parnell was made its president and

Davitt was one of its secretaries. This group united practically all the

different strands of land agitation and land movements since the Tenant

Right League of the 1850s under a single organisation, and from then

until 1882, the "Land War" in pursuance of the "Three Fs" (Fair Rent,

Fixity of Tenure and Free Sale) was fought in earnest. The League

organised resistance to evictions and reductions in rents, as well as

aiding the work of relief agencies. Landlords' attempts to evict tenants

led to violence, but the Land League denounced this. One of the actions

the Land League took during this period was the campaign of ostracism

against the land agent Captain Charles Boycott in Lough Mask House

outside Ballinrobe, Co Mayo, in the autumn of 1880. This campaign led to

Boycott abandoning Ireland in December and coined the word boycott,

which quickly spread across the world and through many languages.

[See:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michael_Davitt]

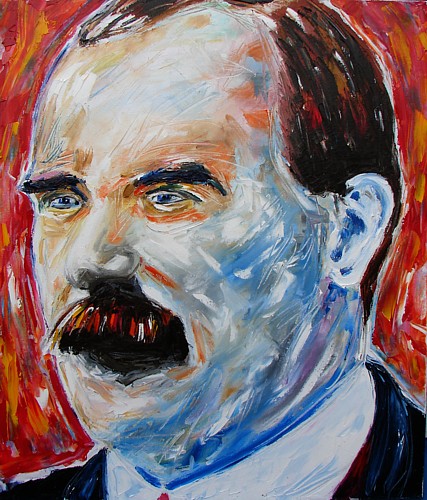

Thomas Clarke (1857-1916)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 70cm

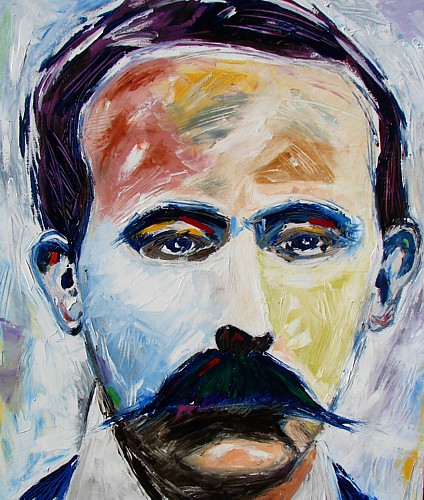

James Connolly (1868-1916)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 70cm

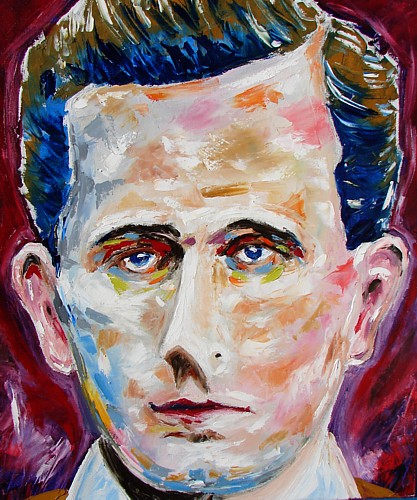

Patrick Pearse (1879-1916)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 70cm

Eamonn Ceannt (1881-1916)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 70cm

Sean Mac Diarmada (1884-1916)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 70cm

Joseph Plunkett (1887-1916)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 70cm

Thomas MacDonagh (1878-1916)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 70cm

Countess Markiewicz (1868-1927)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 70cm

Roger Casement (1864-1916)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 70cm

Sold

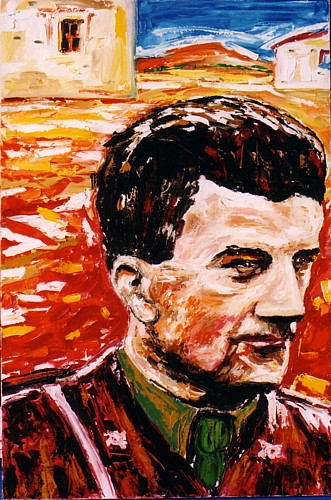

Frank Ryan (1902-1944)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 90cm

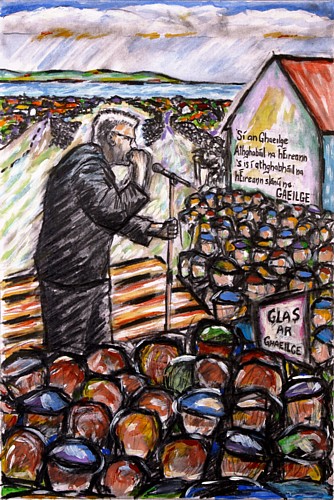

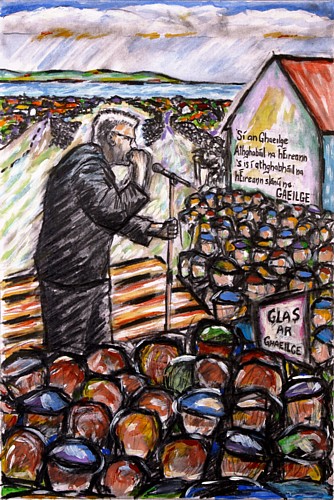

Máirtín Ó Cadhain

(1906 - 1970)

Acrylic and graphite on card / Aicrileach agus

grafít ar chárta

20cm x 30cm

Sold

Scarecrow

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 90cm

Bloody Sunday 1972

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 60cm

Sold

Hold the Rents

Oil and paper on canvas / Ola agus páipéir ar chanbhás-

50cm x 70cm

Sold

First Dáil,

Mansion House, Dublin, 1919

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 70cm

Set Dancing

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 70cm

Sold

Second Dáil,

Mansion House, Dublin, 1921

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

50cm x 60cm

Sold

Allegory

(based on mid-fifteenth-century cadaver

tombstone, Beaulieu churchyard near Drogheda)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

40cm x 80cm

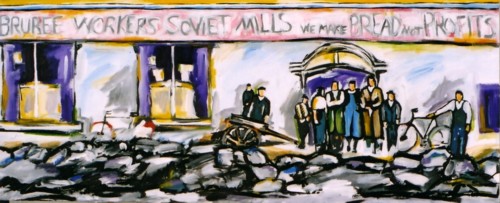

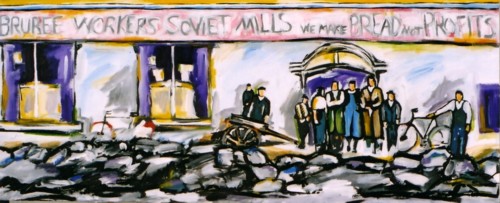

Bruree Workers' Soviet Mills, 1921

Acrylic on canvas / Aicrileach ar chanbhás

30cm x 80cm

Sold

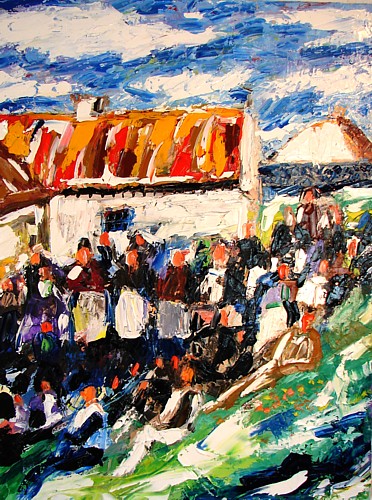

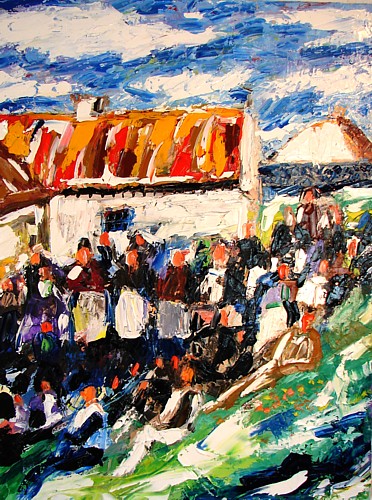

Gweedore, County

Donegal (19c)

Oil on canvas / Ola ar chanbhás

60cm x 80cm

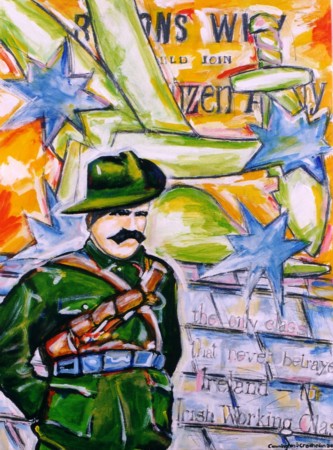

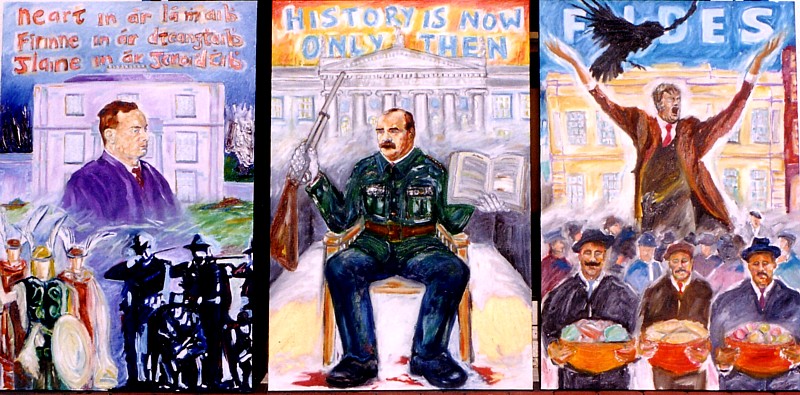

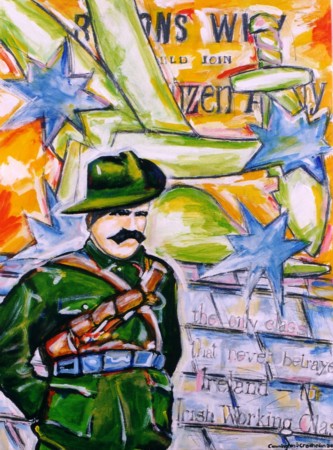

Citizens Army

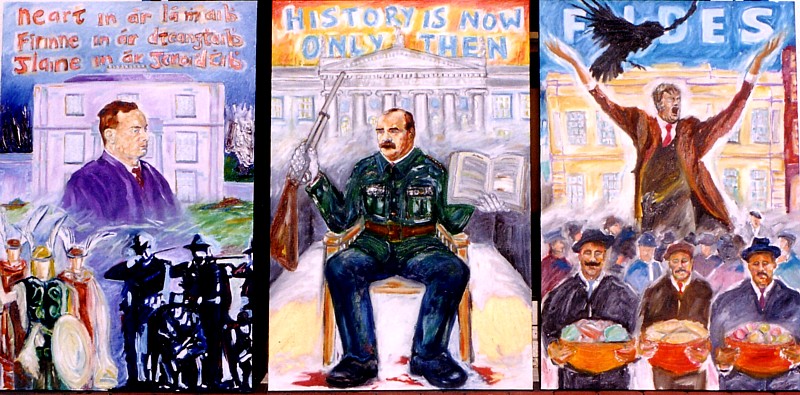

Pearse, Connolly, Larkin Triptych

Home

|