|

The People's Christmas: Art, Tradition and Climate Change

Caoimhghin Ó

Croidheáin 12/12/2018

COME, bring with a noise,

My merry, merry boys,

The Christmas log to the firing ;

While my good dame, she

Bids ye all be free ;

And drink to your heart's desiring.

With the last year's brand

Light the new block, and

For good success in his spending

On your psaltries play,

That sweet luck may

Come while the log is a-teending.

Ceremonies for

Christmas by Robert Herrick (1591–1674)

(Psaltries: a kind of guitar, Teending: kindling)

No season has so much association with music as the mid-winter, Christmas

celebrations. The aural pleasure associated with the tuneful music and carols of

Christmas has been reduced in recent years by the over-playing of same in

shopping malls, banks, airports etc. yet it is still enjoyed and the popularity

of choirs has not diminished.

However, the visual depictions of mid-winter, Christmas celebration have also

been popular since the 19th century through books, cinema and television.

The depictions of Christmas range from religious iconography through to the

highly commercialised red-suited, rosy-cheeked, rotund Santa Claus.

Yet, between these two extremes of the sombre sacred and the commercialised

secular lies a popular iconography best expressed in the realm of fine art and

illustration. Down through the centuries the pagan aspects of mid-winter

celebration and Christmas such as the Christmas tree, the Yule log, wassailing

and carol singing along with winter sports such as ice skating and skiing have

been depicted by many different artists. These paintings and illustrations are

also beloved for the visual pleasure they afford.

More importantly, they show aspects of Christmas which are becoming more

important now in our time of climate change. That is, their depictions of our

past respect for nature.

In recent times, as we gradually learned to harness nature

for our own ends through developments in science we also became less and less

worried about the vicissitudes of nature. Our forebears, however, knew all too

well hunger and cold in the depths of winter and in their own religious and

superstitious ways tried to attenuate the worst of winter hardship through

traditions and practices which would ensure a bountiful proceeding year.

For example, the Christmas Tree is a descendant of the sacred

tree which was respected as a powerful symbol of growth, death and rebirth.

Evergreen trees took on meanings associated with symbols of the eternal,

immortality or fertility (See my article on Christmas Trees

here). Evergreen boughs and then eventually whole evergreen trees were

brought into the house to ward off evil influences. Burning the Yule log was an

important rite to help strengthen the weakened sun of midwinter.

The Christmas Tree (1911)

Albert Chevallier

Tayler (1862–1925)

Wassailing, or blessing of the fruit trees, is also

considered a form of tree worship and involves drinking and singing to the

health of the trees in the hope that they will provide a bountiful harvest in

the autumn. Mumming has also been associated with the spirit of vegetation or

the tree-spirit and is believed to have developed into the practice of caroling

even though mumming is alive and well in many places in Ireland and England. All

these nature-based practices seem to have been banned by the church at different

times and then gradually integrated into church rituals (presumably because the

church was not able to stop them).

Therefore our relationship with nature was demonstrated through winter

activities both inside and outside the home. Outside activities consisted of ice

skating, caroling, wassailing, bringing home the Yule log and the Christmas

tree. Inside activities consisted of large gatherings of family and friends

eating, drinking and parlour games. The indulgence of Christmas activities was

balanced by an overriding concern that nature had been propitiated or appeased.

One aspect the many depictions of these activities have in common is the festive

gathering of large groups of people. Modern depictions of Christmas tend to

emphasise the nuclear family gathered around the Christmas tree with the focus

on what Santa brought for the children. Thus Christmas today is experienced as a

more isolated experience than in the past. The decline of the nuclear family in

recent decades with single parent families, divorce, cohabitation, etc has

created extended family gatherings more akin to the past village groupings.

Outdoor activities have also declined though one can still hear carollers

singing on occasion, though still common in city streets.

Many artists of over the years have tried to depict the essence of Christmas and

midwinter traditions (see my article on midwinter traditions

here) and thus helped to keep them in our consciences.

Let's look at some of the illustrations and paintings that depict mid-winter

festivities over the centuries.

Carole

Carols

Poetry and song are our earliest records of Christmas

celebrations. According to Clement Miles the word "'carol' had at first a

secular or even pagan significance: in twelfth-century France it was used to

describe the amorous song-dance which hailed the coming of spring; in Italian it

meant a ring- or song-dance; while by English writers from the thirteenth to the

sixteenth century it was used chiefly of singing joined with dancing, and had no

necessary connection with religion."[1] The word carol itself comes from the Old

French word carole, a circle dance accompanied by singers (Latin: choraula).

Carols were very popular as dance songs and processional songs sung during

festivals. In medieval times the Church referred to

caroling as “sinful traffic” and issued decrees against it in 1209 A.D. and 1435

A.D.

According to Tristram P. Coffin in his Book of Christmas Folklore,

“For seven centuries a formidable series of denunciations and prohibitions was

fired forth by Catholic authorities, warning Everyman to ‘flee wicked and

lecherous songs, dancings, and leapings’” (p98).

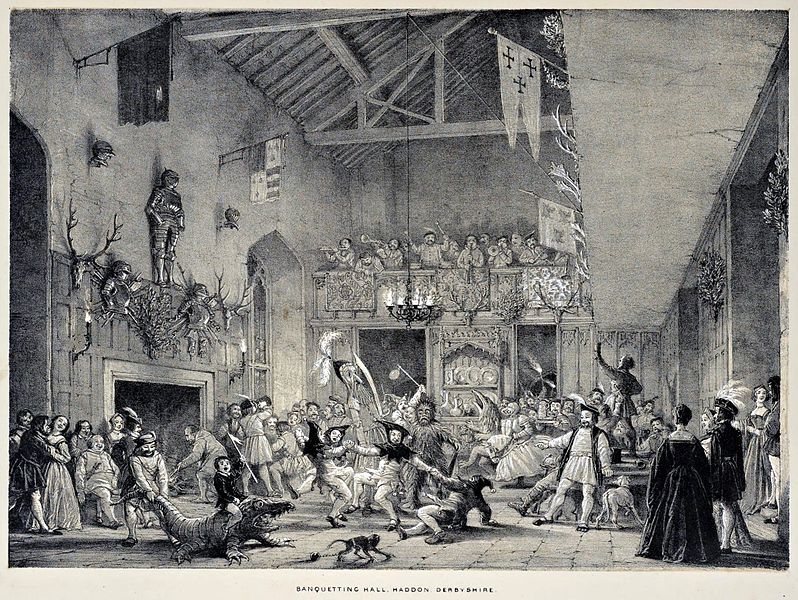

Banqueting Hall

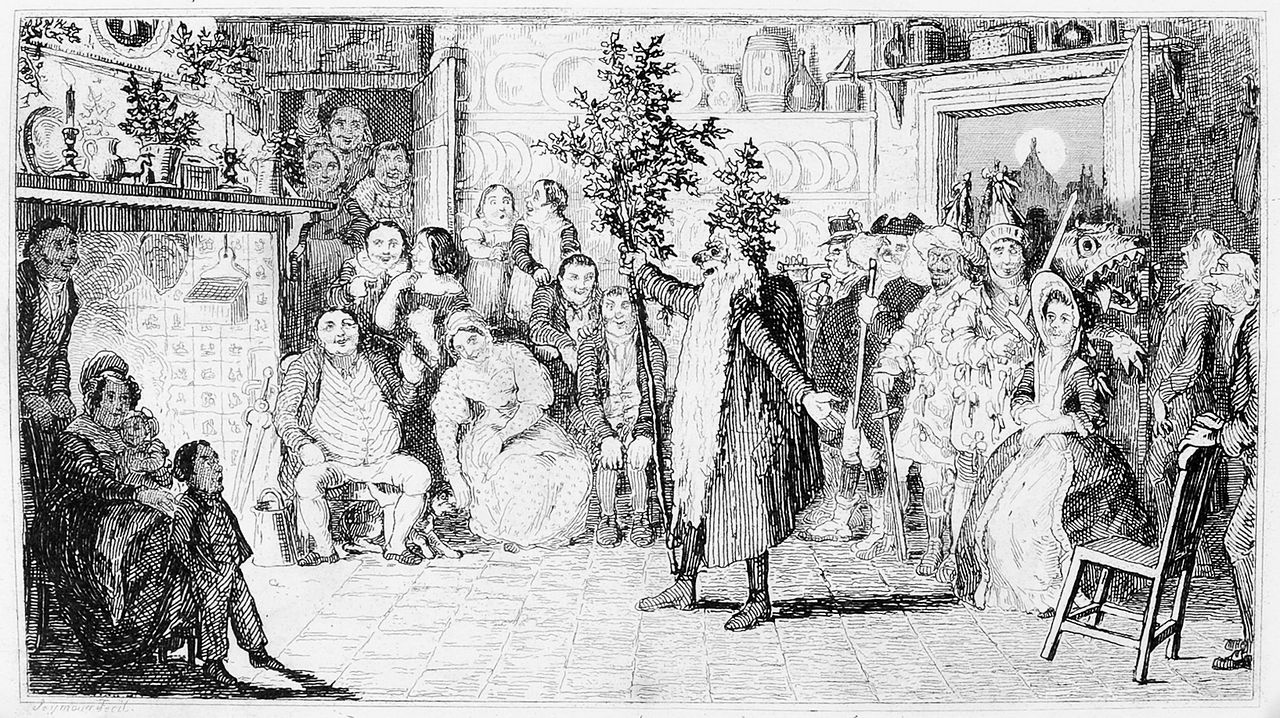

Mumming

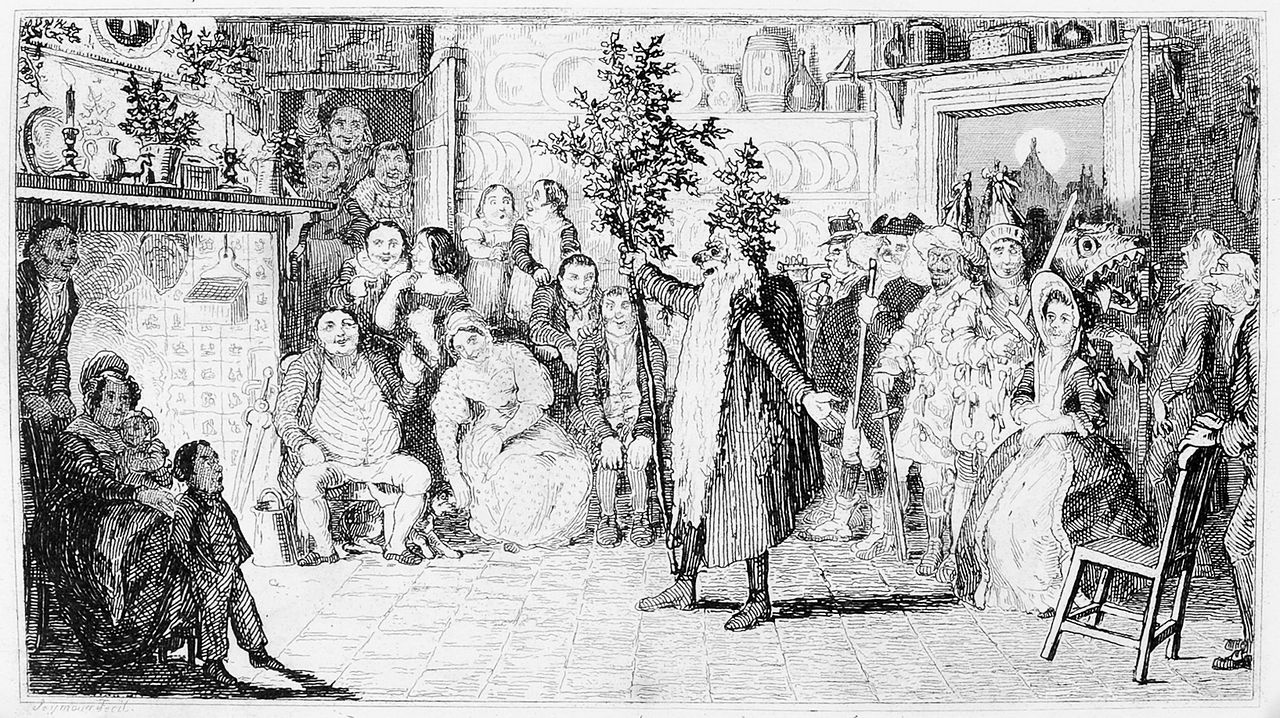

The processional aspects of caroling

are linked to mumming, an ancient tradition which was mentioned in early

ecclesiastical condemnations. During the Kalends of January a sermon ascribed to

St Augustine of Hippo writes that the heathen reverses the order of things as

some of these 'miserable' men "are clothed in the hides of cattle; others put on

the heads of beasts, rejoicing and exulting that they have so transformed

themselves into the shapes of animals that they no longer appear to be men ...

How vile further, it is that those who have been born men are clothed in women's

dresses, and by the vilest change effeminate their manly strength by taking on

the forms of girls, blushing not to clothe their warlike arms in women's

garments; they have bearded faces, and yet they wish to appear women." [2] The

original idea of wearing the hides of animals, Miles writes, may have sprung

"from the primitive man's belief 'that in order to produce the great phenomena

of nature on which his life depended he had only to imitate them'. [3]

Indeed, in Ireland, mumming is a tradition that is still

going strong. In a recent article in The Fingal Independent, Sean McPhilibin

notes that "In North County Dublin the masking would be traditionally made

from straw and would have been big straw hats that cover the face and come down

to the shoulders." McPhilibin also states that mumming was "a mid-winter custom

that in Ireland and North County Dublin and in parts of England as well, the

masking element is accompanied by a play. So there's a play in it with set

characters. It's a play where the principal action takes place between two

protagonists - a hero and a villain. The hero slays the villain and the villain

is revived by a doctor who has a magical cure and after that happens there's a

succession of other characters called in, each of whom has a rhyme. So every

character has a rhyme, written in rhyming couplets.[...] The other thing to say

about it is that you find these same type of characters all across Spain,

Portugal, France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, over into Slovenia and

elsewhere."

James Frazer, in The Golden Bough, discusses at length many international

examples of people being being completely covered in straw, branches or leaves

as incarnations of the tree-spirit or the spirit of vegetation, such as Green

George, Jack-in-the-Green, the Little Leaf Man, and the Leaf King.[4]

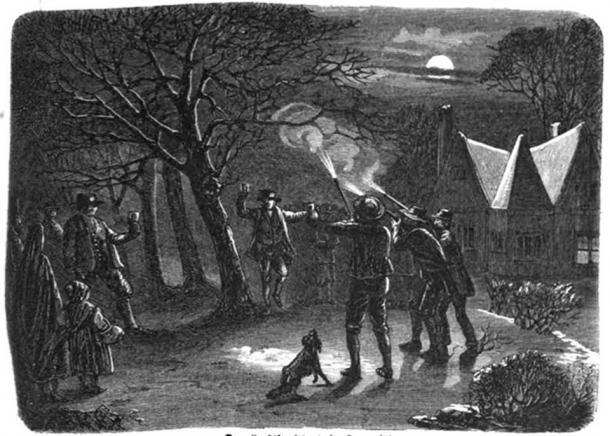

Wassail

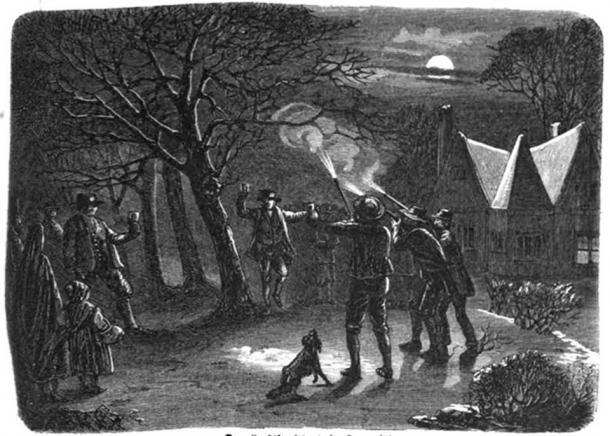

Wassail

The

word wassail comes from Old English was hál, related to the

Anglo-Saxon greeting wes þú hál, meaning "be you hale"—i.e., "be

healthful" or "be healthy".

There are two variations of wassailing: going from house to house singing and

sharing a wassail bowl containing a drink made from mulled cider made with

sugar, cinnamon, ginger and nutmeg, topped with slices of toast as sops or going

from orchard to orchard blessing the fruit trees, drinking and singing to the

health of the trees in the hope that they will provide a bountiful harvest in

the autumn. They sing, shout, bang pots and pans and fire shotguns to wake the

tree spirits and frighten away evil demons.

The

wassail itself "is a hot, mulled punch often associated with Yuletide, drunk

from a 'wassailing bowl'. The earliest versions were warmed mead into which

roasted crab apples were dropped and burst to create a drink called 'lambswool'

drunk on Lammas day, still known in Shakespeare's time. Later, the drink evolved

to become a mulled cider made with sugar, cinnamon, ginger and nutmeg, topped

with slices of toast as sops and drunk from a large communal bowl." (See

traditional wassail recipe

here)

Wassail

The Lord of Misrule

The

Lord of Misrule was a common tradition that existed up to the early

nineteenth century whereby a peasant or sub-deacon appointed to be in charge of

Christmas revelries, thus the normal societal roles where reversed temporarily.

The Lord of

Misrule "would invite traveling actors to perform Mummer’s plays, he would

host elaborate masques, hold large feasts and arrange the procession of the

annual Yule Log."

Mummers by Robert Seymour, 1836

The Mount Vernon Yule Log

Jean Leon Gerome

Ferris (1863–1930)

The Bean King

During the the Twelfth Night

feast a cake or pie would be served which had a bean baked inside. The

person who got the slice with the bean would be 'crowned' the Bean King with a

paper crown and appointed various court officials. A mock respect would be shown

when the king drank and all the party would shout "the king drinks". Robert

Herrick mentions this in his

poem Twelfth Night: or, King and Queen:

"NOW, now the mirth comes

With the cake full of plums,

Where bean's the king of the sport here ;

Beside we must know,

The pea also

Must revel, as queen, in the court here."

Twelfth-night (The King Drinks)

David

Teniers the Younger (1610–1690)

The King Drinks (c.1640)

Jacob (Jacques) Jordaens (1593–1678)

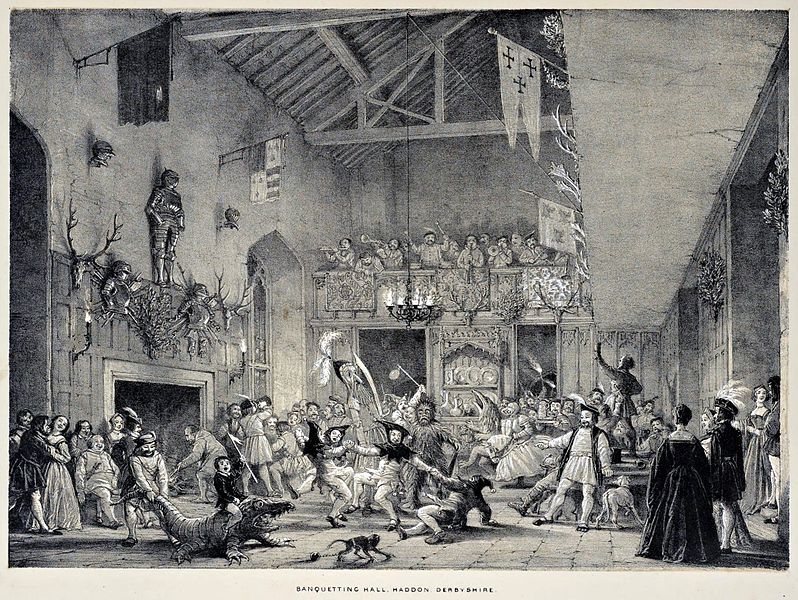

Merry Christmas in the Baron's Hall (1838)

Daniel

Maclise (1806-1870)

Merry Christmas in the Baron's Hall (1838)

Daniel Maclise's painting Merry Christmas in the Baron's Hall (1838) contains

many aspects of the traditional Christmas festivities. The Lord of Misrule

stands in the centre holding his staff and leading the procession of musicians

and carolers coming down the stairs. Father Christmas, 'ivy crown'd', sits in

front of the wassail bowl and is surrounded by mummers (the Dragon and St George

sit side by side) and local people. On the left side of the picture we see a

group of people playing a parlour game called Hunt the Slipper.

Maclise was influenced by Sir Walter Scott's poem Marmion: A Tale of Flodden

Field, published in 1808. Marmion is a historical romance in verse of

16th-century Britain, ending with the Battle of Flodden in 1513.

Marmion has a section referring to Christmas festivities:

"The wassel round, in good brown bowls,

Garnish'd with ribbons, blithely trowls.

There the huge sirloin reek'd; hard by

Plum-porridge stood, and Christmas pie:

Nor fail'd old Scotland to produce,

At such high tide, her savoury goose.

Then came the merry maskers in,

And carols roar'd with blithesome din;

If unmelodious was the song,

It was a hearty note, and strong.

Who lists may in their mumming see

Traces of ancient mystery;

White shirts supplied the masquerade,

And smutted cheeks the visors made;

But, O! what maskers, richly dight,

Can boast of bosoms half so light!"

(See full text

here)

It seems that Maclise was also taken enough by the poem to pen

his own poem about his painting which was published in Fraser's Magazine for May

in 1838. The poem is titled: Christmas Revels: An Epic Rhapsody in Twelve

Duans and was published under the pseudonym, Alfred Croquis, Esq. The

painting includes over one hundred figures covering many different traditions of

Christmas and in his poem Maclise describes most of the activities taking place

as some these excerpts from the poem demonstrate:

"Before him, ivied, wand in hand,

Misrule's mock lordling takes his stand;

[...]

Drummers and pipers next appear,

And carollers in motley gear;

Stewards, butlers, cooks, bring up the rear.

Some sit apart from all the rest,

And these for merry masque are drest;

But now they play another part,

Distinct from any mumming art.

[...]

First, Father Christmas, ivy-crown'd,

With false beard white, and true paunch round,

Rules o'er the mighty wassail-bowl,

And brews a flood to stir the soul:

That bowl's the source of all their pleasures,

That bowl supplies their lesser measures"

(See full text

here)

Winter Landscapes

Winter Landscape near a Village

Hendrick Avercamp (1585 (bapt.) – 1634 (buried))

The Hunters in the Snow (1565)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c.1525-1530–1569)

Winter Landscape with Skaters and Bird Trap (1565)

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c.1525-1530–1569)

These famous winter landscape paintings by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, such as

The Hunters in the Snow and Winter Landscape with Skaters and Bird Trap are all

thought to have been painted in 1565. Hendrick Avercamp also made made many snow

and ice landscapes coinciding with the Little Ice Age. Three particularly cold

intervals have been

described as the Little Ice Age: "one beginning about 1650, another about

1770, and the last in 1850, all separated by intervals of slight warming".

Outdoor Activities: Skating, Markets and Fairs

Patineurs au bois de Boulogne (1868)

Pierre-Auguste

Renoir (1841–1919)

Russian Christmas

Leon Schulman

Gaspard (1882-1964)

The Christmas Market in Berlin (1892)

Franz

Skarbina (1849-1910)

Christmas Fair (1904)

Heinrich Matvejevich

Maniser

Nature-Based vs Anti-Nature

Polydore Vergil (c.1470–1555), the Italian

humanist scholar, historian, priest and diplomat, who spent most of his life

in England, wrote this about Christmas: "Dancing, masques, mummeries,

stage-plays, and other such Christmas disorders now in use with the Christians,

were derived from these Roman Saturnalian and Bacchanalian festivals; which

should cause all pious Christians eternally to abominate them."[5]

However, Clement Miles takes a more positive view of these traditions. He

writes: "The heathen folk festivals absorbed by the Nativity feast were

essentially life-affirming, they expressed the mind of men who said "yes" to

this life, who valued earthly good things. On the other hand Christianity, at

all events in its intensest form, the religion of the monks, was at bottom

pessimistic as regards this earth, and valued it only as a place of discipline

for the life to come; it was essentially a religion of renunciation that said

"no" to the world." [6]

Now we have a religion of consumerism and mass consumption with Santa Claus as

its main protagonist. The one extreme of the sacred St Nicholas has flipped over

to the other extreme of Santa, the corporate saint. Either way the pious and the

consumer pose no threat to the status quo.

Catharsis

There is no doubt that the Christmas festivities were used by elites as a form

of social catharsis. The Lord of Misrule and the Bean King, encouraged by

raucous mummers and lively caroling, allowed the lowly to throw off pent-up

aggression and feel what it was like to be in a position of power for a very

short period of time. This brief social revolution was an important part of

midwinter celebrations such as the Roman Kalends and the Feast of Fools.

Libanius (c.314–392 or 393), the fourth century Greek philosopher, wrote: "The

Kalends festival banishes all that is connected with toil, and allows men to

give themselves up to undisturbed enjoyment. From the minds of young people it

removes two kinds of dread: the dread of the schoolmaster and the dread of the

stern pedagogue. The slave also it allows, so far as possible, to breathe the

air of freedom." [7]

The survivals of an ancient time when man and nature were at peace (see article

here), and not enslaved and forced to overexploit our natural resources for

the benefit of the few, were allowed to resurface briefly at the time of year

when the labouring classes were mostly idle and, once sated, posed little

threat. Yet, retaining the memory of past respectful attitudes towards nature

and old traditions of social upheaval will go a long way towards healing our

damaged home into the future.

Notes:

[1] Clement A. Miles, Christmas Customs and Traditions:

Their History and Significance, Dover Publications, 2017, p47.

[2] Miles, Christmas Customs and Traditions, p170.

[3] Miles, Christmas Customs and Traditions, p163.

[4] James Frazer, The Golden Bough, Wordsworth, 1994. See: The

tree-spirit p297, Green George p126, Jack-in-the-Green p128, the Little Leaf Man

p128 and the Leaf King p130.

[5] Hazlitt, W. Carew, Faiths and Folklore of the British Isles, 2 vols,

New York: Benjamin Blom, Inc., 1965, p118-19

[6] Miles, Christmas Customs and Traditions, p25.

[7] Miles, Christmas Customs and Traditions, p168.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and

writer. His

artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as

well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing

based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist

and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country

here. He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on

Globalization.

|